Ethiopia and the perils of war January 10, 2021

Posted by OromianEconomist in Uncategorized.trackback

Ethiopia and the perils of war

In conversation with Eritrean human rights activist Paulos Tesfagiorgis

Pierre Beaudet, Canadian Dimension / January 8, 2021

Paulos Tesfagiorgis was the head of the Eritrean Relief Association (ERA) and one of the senior cadres of the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front (EPLF) from the 1970s until the liberation of the country in 1991. While EPLF liberated Eritrea, opposition forces in Ethiopia, under the leadership of the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) and its coalition partners, also succeeded in establishing a new government in Addis Ababa. The hope then was that both Ethiopia and Eritrea would cooperate in rebuilding. But that did not come to pass. Under the leadership of the EPLF and new president Isaias Afwerki, Eritrea escalated a border skirmish into an all-out war which caused a great deal of destruction and animosity for another two decades. Like many of his former comrades, Tesfagiorgis was forced into exile. Many senior EPLF and government cadres were detained and disappeared, never to be seen again.

Recently, in 2018, there was a shift in power with the arrival of Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, who looked to be a champion of peace and democracy. He pushed the TPLF out of the commanding heights they had occupied for many years. He released political prisoners and relaxed control over the press. And he signed a peace accord with Eritrea. His actions inspired confidence and resonated with a large swath of Ethiopian society. He appeared to have a strong mandate to pursue and consolidate his reform agenda.

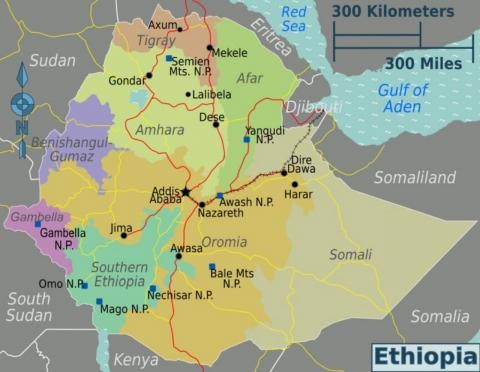

It was not too long, however, before conflict erupted once again. The battle between the TPLF and members of the new Ethiopian power circle, to which the prime minister seemed beholden, finally exploded dramatically in 2020 when the TPLF pulled out of Addis, held its own elections, and took over the Ethiopian military bases in Tigray, apparently to pre-empt the prime minister from using them against Tigray. The Ethiopian government responded by launching a full-scale invasion of Tigray on November 4. Two months later, Ethiopian military forces are now occupying the main towns, including the Tigrayan capital, Mekelle, with the support of Eritrea. TPLF battle-hardened troops went into the hills, promising a battle to the finish, and to make Tigray the “burial ground of the invaders.”

What are the prospects for peace, now, at what appears to be the beginning of a protracted war? What can be expected from other Horn of Africa countries? Canadian Dimension put these questions to Tesfagiorgis, who has been carefully observing the situation by keeping in touch with many of his former comrades and friends in Ethiopia, Tigray and Eritrea.

What is happening on the ground in Tigray?

It is very difficult to know much under the circumstances. Apparently, battles are taking place in many regions of Tigray. More than 70 percent of the Ethiopian army is now in Tigray. According to Mesfin Hagos, Eritrea’s former chief of staff and minster of defense, the Eritrean president sent 11 mechanized divisions, four infantry divisions and two commando divisions in addition to providing intelligence, logistics and heavy armaments. This makes one wonder who is doing the actual fighting. Despite this enormous deployment, TPLF seems to be able to inflict major losses, including destroying tanks and heavy armaments and taking prisoners of war, although so far we have not seen related footage or photos. Nonetheless, human and material costs seem to be quite high on the Ethiopian side. Although the extent of the TPLF’s losses is unknown, we can presume they have also sustained serious damage but it is likely that they were well prepared. They know how to fight, and they know their terrain. They can also count on the support of most of the people in Tigray who might not necessarily like the TPLF’s policies and practices, but who will support them in face of an Ethiopian assault which has already badly affected civilians.

Is the situation heading towards a protracted war?

I see it as a real possibility. Despite their quantitative strength, I do not think the government forces can crush the TPLF easily. There are many questions about the quality of their military leadership, since until 2018 the Ethiopian army was led by TPLF senior commanders who have defected en masse to join the resistance. Ethiopian soldiers who come from various nationalities do not necessarily have the training and motivation that one finds on the Tigrayan side, united by the call to “defend the nation.” Ethiopia, one should not forget, is still a very poor country, despite its relative economic success in the past decade and half, and thus will not be able to sustain a fight with a well-organized, well-trained and highly motivated army without its economy collapsing or the country risking ultimate disintegration.

Can the involvement of Eritrean forces make a difference?

If the evidence that we have until now is confirmed, the Eritrean military is playing a leading role. Although militarily effective, this could be dangerous politically. The conflicts between Eritrea and Tigray, and more specifically between EPLF and TPLF, are deeper and have a long history. Eritrean domination and participation in the war would appear as a foreign invasion. That would make Ethiopians, let alone Tigrayans, very uncomfortable. All in all, I see the possibility of a protracted war that will sap Ethiopia’s energy, distract its attention from resolving the many problems that it is encountering in different places, and put a damper on economic activity and development projects.

Was this disaster unavoidable?

It is a complex and multi-dimensional crisis; nothing could have been easily resolved. It would have required years, perhaps decades, to build a genuine political space, institute dialogue as a participatory political process and improve the lives of ordinary people. There were some positive signs in 2018 as Ethiopia moved towards democratization to some extent. The sort of “ethnic federalism” that emerged in the 1990s had its limitations, but it also had benefits. Ethiopia had to find a way out of the oppressive heritage of the feudal regime of Haile Selassie and the barbaric military junta of Mengistu, who had cultivated the idea that the country was the property of the Amhara elite, and that the others were all ignorant peasants. Ethiopian federalism was based on ethnicity, a system that sought to empower the historically subjugated and the minority ethnic groups. It was not easy to redesign the constitution and the governance structures of this type of federalism so that finances, power and resource-sharing, security, services, etc. functioned as they should. Another challenge is that minorities also live within minorities. It was unclear whether they would be asking to assert their identity and claim their right to govern themselves and whether they would be treated as equal to the minorities among whom they live. The TPLF, which dominated the government, did try, but did not really understand the complexity of the situation, nor, in the later years, was it adequately prepared. The marginalized are now expected to rally around the newly created Prosperity Party and Prime Minister Abiy, which claim to have come up with some sort of a reform agenda, but without the required depth, relevance, sophistication, patient dialogue and negotiations.

But then, everything has broken down…

I think that Abiy and the new Ethiopian ruling class were unable to grasp the consequences of the conflict with TPLF, even before the dramatic escalation of the last two months. The thinking was that the new government could force the TPLF to accept the inevitable—losing their grip on power in Addis and remaining silent forever.

Abiy miscalculated…

Despite many differences between political and social groups and ethnic identities in Ethiopia, there was a deeply felt and shared desire that Ethiopia no longer be ruled by the TPLF. But it seems a strategic mistake to think that they can easily be dislodged in Tigray. Abiy did not understand that the TPLF is rooted in the society for historical reasons. Bear in mind too that last summer the TPLF won a huge majority in the Tigray elections, which were, by the way, transparent, free and fair. This can also be taken as a new mandate given by the people to the TPLF to govern the region. At the end of the day, going to war against the TPLF was and is a serious failure of leadership and of statecraft; it is a failure to think beyond the present and appreciate the damage that it can cause to people’s lives and livelihood as well as to the economy and the unity of the country.

Tell us a bit more about the role of Eritrea in this confrontation.

I have suggested before that the huge Eritrean military presence is one of the reasons that Ethiopia can maintain its occupation of Tigray. It seems that Afwerki had planned this war a long time ago. He had an axe to grind with the TPLF whose forces had defeated him in the war of 1998-2000, which he took as a personal humiliation. Apparently, Abiy looked up to the Eritrean leader when it appeared that the conflict with Tigray was intensifying. He wrongly believed that the solution was to eliminate the TPLF or at least undermine it strategically through quick surgical military action. What a blunder!

Eritrea will ultimately pay the price.

I am extremely sad that my country is involved. It is not that Eritrea has no issues with the TPLF. The non-acceptance of the border decision and refusal to implement an international ruling has left bad blood between Eritreans and the TPLF. The nearly two decades of no-war-no-peace that ensued from this refusal gave the Eritrean dictator an excuse to suspend all freedoms, democratization, development and the implementation of a constitution that was made by the people. But if one thinks about peace and reconstruction, reverting to war is madness. War begets war. It is only a matter of time. Military conflict can only exacerbate and complicate the relationship for a long time, delaying cooperation and integration that is much needed in the region. My country, my people, young and old, will bear the burden of the ongoing war. Only candid discussions and a patient dialogue can lead to reconciliation, by telling the truth about the damage inflicted on both sides and looking for a long-term solution that would promote peace, security and prosperity for the peoples of Eritrea and Tigray and the people of Ethiopia more broadly.

What about Ethiopia? Who will pay?

Ethiopia was regarded as an anchor of peace and stability in the Horn of Africa region with all its problems. No more! As a matter of fact, it now runs the risk of becoming a source of instability in the region with unimagined consequences. A revealing side story is that Ethiopia is now pulling out of United Nations peace keeping operations in Somalia and South Sudan. Abiy, after having won the Nobel Peace Prize for his effort to make peace with Eritrea, seems to have gone to war with his own country, against his own people. Tigrayans are Ethiopians! They will always remain there. In the meantime, there is a renewed political squeeze in the rest of Ethiopia: political party leaders are in prison, some parties have been deregistered, and others have stated they will not participate in the 2021 elections in the present climate of intimidation. Ethiopia seems to have gone back to the dark days of the 1980s when extrajudicial killings were the order of the day, and slaughter, displacement and a heavy cloud of silence and fear dominated everyday life. Independent media that flourished in the last few years have resorted to self-censorship.

What about security?

It is evident that security is threatened in many regions of Ogaden, Afar, Beni Shangul and other places. There is unrest in many parts of Ethiopia, including armed resistance, massacres, and ethnic cleansing. Militias are taking the law into their own hands; these are ill-trained, ill-disciplined, marauding criminals creating chaos and destruction. They can easily turn into mercenaries, doing the dirty work of whoever pays them more. The recent massacre in Mai Kadra, where the bodies of over 600 civilians were recovered, is said to have been committed by militias. Whether they were Amhara or Tigrayan militias does not make much difference, although initial investigations seem to indicate that Amhara militias committed the massacres.

What about the situation in Oromia?

As I indicated earlier, the regular Ethiopian defence forces are needed in many other places in Ethiopia, but they are concentrated in Tigray. The dissatisfaction that expresses itself in violence in Oromia has not been addressed yet and might not be if the tactic that is being employed by the government is to instill fear through imprisoning their leaders, accusing them of terrorism and shooting them in broad daylight, instead of creatively confronting the huge problem of youth unemployment that manifests itself in sporadic destructive activities.

What about the situation of the Tigrayans outside Tigray?

Ethnic profiling is being practiced against the Tigrayans in the rest of Ethiopia, especially in the capital, Addis Ababa. Tigrayan businesses are closed. Tigrayans cannot access their bank accounts. Tigrayans are dismissed from government jobs and prevented from travelling. They are refused boarding on Ethiopian Airlines, for example. This is not going to disappear, especially if the military campaign fails and the invasion of Tigray is not quickly lifted. This might also escalate into massacres that will complicate peace efforts in Ethiopia for generations and discourage Tigrayans from wanting to remain a part of Ethiopia.

What is the role of global actors in all this?

The United States, which was historically an ally of Ethiopia, is expressing its discontent with the ongoing violence and the involvement of Eritrea. At this point, it is hard to discern a real strategic approach by the international community. The European Union and China, which have big economic stakes in Ethiopia, have little political influence and leverage, and additionally, limited capacities to pressure the Ethiopian government to change course.

And the regional powers?

The main regional governments such as Sudan and Kenya seem to have a problem with Ethiopia. Both in the past and at present, Egypt and Ethiopia have had many conflicts, mainly revolving around the waters of the Nile River. Sudan, on the other hand, has had several land-based conflicts with Ethiopia that are threatening to get out of hand. Eritrea is clearly on the side of Ethiopia and sees chaos as suiting its designs. Djibouti is quiet, perhaps wisely. Somalia supports Ethiopia but without throwing any meaningful weight around one way or the other, as the government is unstable and dependent on outside forces for its own security. Because of the many aggravating crises in these countries, it is unlikely that they can intervene with the necessary means and sufficient credibility to promote some sort of peace process. What exacerbates this passivity is the historical fact that the policy of many states in the region has been locked into the false principle that the “enemy of my enemy is my friend.” All these countries have supported their neighbours’ opposition groups. To close this chapter, foreign intervention in the affairs of the Horn countries is a historical reality. No one can believe that Saudi Arabia and the Emirates, which have become the “new friends” of Ethiopia, can play any constructive role except dispensing money to different warring factions. What they have done in Yemen, Libya, Syria indicates that no one has confidence they can play a constructive role or bring about any positive change.

Does this sustain the TPLF’s hope of finding regional allies?

The rumour is that the TPLF is already lobbing Khartoum and Cairo, at least to gain open access to these countries and obtain some passages for supplies, as was the case with the Eritrean liberation movement and the TPLF until 1991. But in the current confused and dangerous situation, external states will think twice before getting involved with forces, on both sides, which are playing with fire. But the longer this conflict continues the more it risks drawing in other interested parties, complicating the situation even more.

In this very dark moment, what can we hope for?

I would be surprised if there are no sane voices in Addis Ababa or the rest of Ethiopia for that matter. I am certain there are many who not only disagree with the war but who are pained by the loss of life, loss of resources and loss of opportunities. Many academic and research institutions have sprouted up in Ethiopia. Many professionals and highly skilled and experienced people exist. They have also witnessed the mistakes and blunders of the TPLF and, I very much believe, were ready to participate in correcting them. There is a new generation out there that must strive to move beyond the conception of Ethiopia as a centralized state dominated by a single ethnic group. The present and future well-being of Ethiopians depends on jettisoning the pan-Ethiopianist vision, which is as unjust as it is unworkable.

Young Tigrayans and other Ethiopians have gone to the same universities in Ethiopia. Many have come to study in Mekelle University in Tigray and lived safely, interacting with each other. These are potential allies. Given the opportunity, they could make genuine efforts to resolve these seemingly intractable problems and lay the foundations for all citizens to live in harmony as one people in a peaceful country.

Ethiopia has gone through several interesting stages in its history. It had its glorious days when it defeated outside conquerors and established modern institutions. It also had its dark times. In the end it has proved incredibly resilient.

What can we expect from the current rulers both in Ethiopia and Tigray?

I would hope that some of the leaders will stop the killing and resolve their differences politically through dialogue. Yes, it would be a not so small miracle! On the Ethiopian side, the grave mistakes committed by Abiy must force serious rethinking within the ruling group. We can hope that some people will step up and challenge the idea that smashing the TPLF or suppressing other regional identities is a sustainable policy. The TPLF must also do some hard thinking. They cannot risk an endless war that would ruin Tigray for decades. It might be difficult to change their mindset informed by their past history of military success under difficult conditions, but they have enough young members who can help to shift their politics of force and manipulation to a politics of negotiation, power-sharing and respect for those who do not think like themselves.

Dialogue is not always easy; it can also be time consuming. But, in the end, it can work and the reward benefits everyone—the country and the people—helping to usher in the bright future that Ethiopia and Ethiopians deserve.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Pierre Beaudet is active in international solidarity and social movements in Québec. He teaches international development at the University of Québec Outaouais campus in Gatineau. He is founder of the Québec NGO Alternatives, and editor of Nouveaux cahiers du socialisme.

Related articles from Oromian Economist sources:-

2021 Emergency Watchlist

Crisis in Ethiopia: New conflict threatens the region

“With over 21 million people already in need of humanitarian assistance and this number now rising due to the crisis in Tigray, we must ensure that nothing disrupts humanitarian access and programming,” says Richard Data, the IRC’s interim deputy director of emergencies for Ethiopia.

Situation Report EEPA HORN No. 51 – 10 January 2021

Ethiopian women raped in Mekelle, says soldier

FP: THE YEAR IN REVIEW: Is Ethiopia the Next Yugoslavia?

Eritrea’s brutal shadow war in Ethiopia laid bare

New video backs extensive Telegraph reports pointing towards egregious abuses, including massacres and pillaging

Satellite Images Show Ethiopia Carnage as Conflict Continues

Abiy Ahmed and the Consolidation of Ethiopia’s Dictatorship

FIFA is set to move its Regional Office from Addis Ababa to Kigali

All Is Not Quiet on Ethiopia’s Western Front

War-Torn Ethiopian Region Still Wracked by Fighting, UN Says

Viewpoint: Why Ethiopia and Sudan have fallen out over al-Fashaga

Mounting violence in Ethiopia exposes deepening fault lines and leadership crisis

Comments»

No comments yet — be the first.