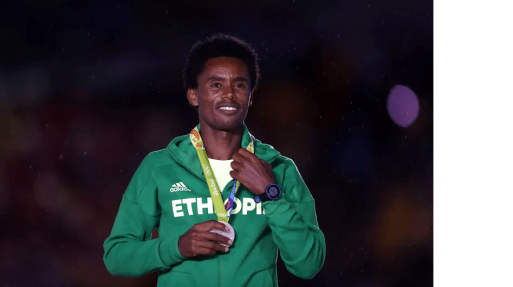

After nabbing a silver medal in Olympic marathon, Ethiopian runner Feyisa Lilesa hoisted his arms inches above his head in the form of an “X.”

With a seemingly innocuous gesture, the 150-pound black man was actually displaying a symbol of solidarity with the Oromo people of Ethiopia, who have protested the government’s reallocation of their land. At least 400 local protesters were killed by Ethiopian security forces over the last year, according to Human Rights Watch. The “X” symbol that Lilesa showed came into widespread use in Ethiopia four and half years ago by protesters as a mark of unarmed, civil resistance.

Following his demonstration, which he repeated on the medal stand, Lilesa toldreporters in Rio De Janeiro, “If I go back to Ethiopia, the government will kill me.” That’s the cost of protesting a government in Ethiopia that controls its media and stifles those who speak out against its will.

#OromoProtests: #FeyisaLilesa to @ESATtv “many are dying and the regime must be removed by collective action”

After Lilesa’s protest, James Peterson, the Director of Africana Studies at Lehigh University spoke to many Ethiopians in America who felt galvanized by the gesture despite the ongoing human rights violations in their homeland.

“There are a lot of complicated things folks don’t understand about continental African politics,” Peterson said. “Addis (Ababa) as a city is sort of engaged in this moment of neoliberal straw. The city is trying to expand at the expense of these rural and suburban settlements that have been in place for like thousands of years. For an Ethiopian athlete, on the largest stage of any Ethiopian of the world right now at the Olympics, to be in solidarity with them, I don’t think it’s too much to say this is the equivalent of some of the most courageous, solidarity protests that we’ve seen in athletics.”

Olympians have long used the games as a stage to draw attention to national causes.Tommie Smith and John Carlos gave a black power salute on the podium at the 1968 Summer Olympics during an American wave of Civil Rights. After Simone Manuel’s historic gold medal, she also spoke out about police brutality and black lives in America.

Such acts have caused the International Olympic Committee executive board to ban political or religious demonstrations in multiple ways in their Olympic Charter Rule 50and can result in the “disqualification or withdrawal of the accreditation of the person concerned.”

Yet for Lilesa’s protest, his defiance of the Ethiopian government didn’t open up a new wave of Oromo activism. But it did demonstrate their current struggle for the world’s purview.

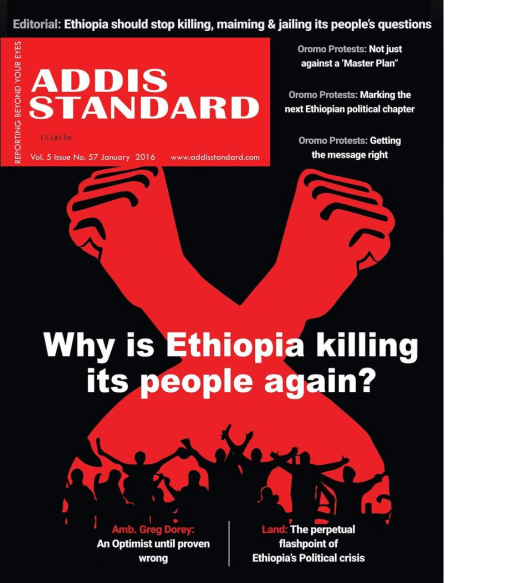

“Ethiopia has been praised as a poster child for peace and stability in the last 25 years. Western governments that continued financing this government, including the U.S. Government, have turned their eyes away,” Tsedale Lemma, the editor-in-chief of the Addis Standard, a monthly magazine focusing on Ethiopian current affairs from the country’s capital Addis Ababa, told SB Nation.

“To be able to tell this to the world, where everyone can see, on this stage was monumental,” she said. “It was telling the world to its face that this country, this poster child of peace, isn’t that way. It’s killing its own people. When everyone kept silent in the wake of this excessive killing, this young man (protested) at the great cost that he might not be able to come back to his country afterwards.”

Lemma’s magazine shares the same views as Lilesa. In January, it published a widely shared cover. Employees were intimidated and threatened, and the publication’s subscription numbers in Ethiopia have drastically declined for questioning the government.

Since the Ethiopian government announced plans in 2014 to expand the territory of the capital Addis Ababa, the country has been racked with protests resulting in hundreds of deaths at the hands of the government. Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn wanted to further Addis Ababa’s territory into Oromia, where Lilesa lives.

Doing so would displace many of the Oromo people in Ethiopia who work on farmlands. It’s similar to American eminent domain, the right of the government or its agents to expropriate private property for public use. Oromo people are the largest ethnic group in Ethiopia, accounting for nearly 40 percent of its population, according to a 2007 census.

Historically, the Oromo people have been marginalized by the government. Protests started in November; and though the government has dropped proposals to widen the capital in January, protests have continued, though, with citizens corralling for wider freedoms.

Local residents and Oromos between the United States and Ethiopia have claimed that thousands have also been jailed. Many incidents happened where the Oromo have gone to the streets and they almost always end in violence. They are killed. They are exiled or tried for treason. At best, the protestors just disappear from sight.

Within Ethiopia, Oromos mostly expressed their support for Lilesa on social media, Lemma said. Current government mandates do not tolerate people flooding the streets for celebration, particularly not for a man that flashed a symbol that is the nightmare for a regime in front of billions of people.

State-run media only showed a censored version of the marathon Lilesa won, and completely blocked his protest at the games. Some have refused to mention his name at all. But in the United States, where Ethiopians are the fifth–largest source of black immigrants, their ebullience was overflowing.

“Among his compatriots, including those in the diaspora, Lilesa’s protest was welcomed with tears of joy,” said Mohammed Ademo, the founder and editor of OPride.com that aggregates Oromo news. “A hero was born out of relative obscurity. A GoFundMe account was set up within hours. I have no doubt that it will be remembered as a watershed moment in the history of Oromo people.

“Kids will be named after him. Revolutionary songs and poems will be written in his honor. For a people who have been silenced for so long this is likely to embolden and generate more momentum for the budding movement in Ethiopia.”

The overwhelming thought is that the plight of the Oromo people, and Lilesa’s protest shedding light on it, are not what Ethiopia wants the world to know. It is an extremely censored country, where most newspapers and other outlets are either controlled or affiliated with the government.

One woman, who asked for anonymity to speak to SB Nation because she feared the consequences of speaking out against the Ethiopian regime for her and her family, said that when she last visited Ethiopia around the start of the protests, the government had blocked internet service and scrambled social media apps to stop people from collaborating by using them, a form of silencing dissent.

She said Lilesa’s feat exemplifies how fearful a lot of the Ethiopian diaspora is to speak out on this subject.

“(Lilesa) acknowledged the significance of this dialogue and that he may never walk the land he’s from or see his family again,” she said. “It was meaningful and it’s going to spur the type of international engagement that is necessary to challenge the Ethiopian government to recognize their faults and consider what a just government looks like.”

American media still largely ignores the African continent and most news organizations have dramatically cut their African bureaus or rely on one person to cover the entire continent. There’s more coverage generally on terrorism with direct implications for American national security, Ademo said.

There also hasn’t been much coverage of the Oromo protests. One reason is because Oromia has largely been off-limits to journalists since the protests began, and those who go to Ethiopia often face insurmountable hurdles for access, Ademo said.

Even Lilesa’s dominance as a marathoner is unique for Ethiopia. Ethnic Oromo athletes of all genders have often been erased from Ethiopian lore, yet they are the first black Africans to win Olympic gold, Ademo said. Abebe Bikila did so in the 1960s while running barefoot and Derartu Tulu followed in the 1992 and 2000 Olympics. Yet behind the scenes these same athletes faced implicit and explicit biases.

Few Oromo athletes spoke Amharic, a language of power in Ethiopia, and they were never sent with Oromo translators. They often had to operate by the doctrine of the country’s current rulers and the official Olympics body to compete, Ademo said.

Within Ethiopia, those who protest see these same issues at the micro level. Lemma described a phrase many have used to explain the discrimination and marginalization the Oromo face. Oromo have said “the prisons in Ethiopia speak Afaan Oromo,” the native language of the Oromo, which shows the disproportionate rate at which Oromo are jailed in Ethiopia.

Video this month, obtained by the Associated Press, showed Ethiopian security forces beating, kicking and dragging protestors during a demonstration in the capital as they cowered and fell to the ground.

This same fight to upend oppression in Ethiopia is one being done by current American black protestors at the height of a renewed wave of activism. Lilesa’s protest spoke to some on a bigger level. Because just like black lives, African lives also have value.

“Not even in just this particular incident, but the dominance of black athletes on the global stage is in a sense of protest, especially when you have representatives of countries under such oppression as Ethiopia and the black America,” said Kwame Rose, an activist from Baltimore most known for his stand-off with Fox News commentator Geraldo Rivera after Freddie Grey’s death.

“What he did would get a lot of people killed in Ethiopia and could’ve gotten his medal stripped,” Rose continued. “This was the time to send a message, not only about competing as an athlete, but surviving as a human and trying to better humanity.”

The reality is that what Lilesa did might not change anything for the Oromo people, but his demonstration had much more validity than to be limited to just that notion.

Ademo said it provided a crucial show of inspiration for people being disproportionately jailed, that are unheard and have yearned for a change in their government.

“In the context of this long and tortuous history, Lilesa’s protest was revolutionary. Beyond the politics within the Ethiopian Olympics federation, his gesture brought much-needed attention to escalating human rights abuses in Ethiopia,” Ademo said.

Lilesa’s act was a moment to show the shackles of systemic oppression binding the Oromo people. He took their fight to the international stage.

You must be logged in to post a comment.