Ethiopia’s Land & Water Grabs Devastate Communities: New Satellite Imagery Shows Extensive Clearance of Land Used By Indigenous People to Make Way for State-Run Sugar Plantations February 25, 2014

Posted by OromianEconomist in Africa Rising, African Poor, Agriculture, Aid to Africa, Development, Dictatorship, Domestic Workers, Environment, Ethiopia's Colonizing Structure and the Development Problems of People of Oromia, Afar, Ogaden, Sidama, Southern Ethiopia and the Omo Valley, Ethnic Cleansing, Food Production, Hadiya, Human Traffickings, ICC, Janjaweed Style Liyu Police of Ethiopia, Kambata, Knowledge and the Colonizing Structure. African Heritage. The Genocide Against Oromo Nation, Land and Water Grabs in Oromia, Land Grabs in Africa, Ogaden, Omo, Omo Valley, Oromia, Oromiyaa, Oromo, Oromo Nation, Oromo the Largest Nation of Africa. Human Rights violations and Genocide against the Oromo people in Ethiopia, Self determination, Sidama, The Colonizing Structure & The Development Problems of Oromia, The Tyranny of Ethiopia, Uncategorized.Tags: Africa, African culture, African Studies, Developing country, Development, Economic and Social Freedom, Economic development, Economic growth, economics, Ethiopia, Gambella and Omo Valley, Genocide against the Oromo, Human rights, Human Rights and Liberties, Land grabbing, Land grabs in Africa, National Self Determination, Oromia, Oromia Region, Oromiyaa, Oromo, Oromo culture, Oromo people, Sub-Saharan Africa, Tyranny, United Nations, Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Water and Land Grabs in Ormia, World Bank

1 comment so far

‘Ethiopia’s Lower Omo Valley, a UNESCO World Heritage site and home to 200,000 agro-pastoralists, is under development for sugar plantations and processing. The early stages of the development have resulted in the loss of land and livelihoods for thousands of Ethiopia’s most vulnerable citizens. The future of 500,000 agro-pastoralists in Ethiopia and Kenya is at risk.’ – Human Rights Watch

http://www.hrw.org/node/123131

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/lori-pottinger/ethiopia-pushes-river-bas_b_4811584.html

(Nairobi) – New satellite imagery shows extensive clearance of land used by indigenous groups to make way for state-run sugar plantations in Ethiopia’s Lower Omo Valley, Human Rights Watch and International Rivers said today. Virtually all of the traditional lands of the 7,000-member Bodi indigenous group have been cleared in the last 15 months, without adequate consultation or compensation. Human Rights Watch has also documented the forced resettlement of some indigenous people in the area.

The land clearing is part of a broader Ethiopian government development scheme in the Omo Valley, a United National Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage Site, including dam construction, sugar plantations, and commercial agriculture. The project will consume the vast majority of the water in the Omo River basin, potentially devastating the livelihoods of the 500,000 indigenous people in Ethiopia and neighboring Kenya who directly or indirectly rely on the Omo’s waters for their livelihoods.

“Ethiopia can develop its land and resources but it shouldn’t run roughshod over the rights of its indigenous communities,” said Leslie Lefkow, deputy Africa director at Human Rights Watch. “The people who rely on the land for their livelihoods have the right to compensation and the right to reject plans that will completely transform their lives.”

A prerequisite to the government’s development plans for the Lower Omo Valley is the relocation of 150,000 indigenous people who live in the vicinity of the sugar plantations into permanent sedentary villages under the government’s deeply unpopular “villagization” program. Under this program, people are to be moved into sedentary villages and provided with schools, clinics, and other infrastructure. As has been seen in other parts of Ethiopia, these movements are not all voluntary.

Satellite images analyzed by Human Rights Watch show devastating changes to the Lower Omo Valley between November 2010 and January 2013, with large areas originally used for grazing cleared of all vegetation and new roads and irrigation canals crisscrossing the valley. Lands critical for the livelihoods of the agro-pastoralist Bodi and Mursi peoples have been cleared for the sugar plantations. These changes are happening without their consent or compensation, local people told Human Rights Watch. Governments have a duty to consult and cooperate with indigenous people to obtain their free and informed consent prior to the approval of any project affecting their lands or territories and other resources.

The imagery also shows the impact of a rudimentary dam built in July 2012 that diverted the waters of the Omo River into the sugar plantations. Water rapidly built up behind the shoddily built mud structure before breaking it twice. The reservoir created behind the dam forced approximately 200 Bodi families to flee to high ground, leaving behind their crops and their homes.

In a 2012 report Human Rights Watchwarned of the risk to livelihoods and potential for increased conflict and food insecurity if the government continued to clear the land. The report also documented how government security forces used violence and intimidation to make communities in the Lower Omo Valley relocate from their traditional lands, threatening their entire way of life with no compensation or choice of alternative livelihoods.

The development in the Lower Omo Valley depends on the construction upstream of a much larger hydropower dam – the Gibe III, which will regulate river flows to support year-round commercial agriculture.

A new film produced by International Rivers, “A Cascade of Development on the Omo River,” reveals how and why the Gibe III will cause hydrological havoc on both sides of the Kenya-Ethiopia border. Most significantly, the changes in river flow caused by the dam and associated irrigated plantations could cause a huge drop in the water levels of Lake Turkana, the world’s largest desert lake and another UNESCO World Heritage site.

Lake Turkana receives 90 percent of its water from the Omo River and is projected to drop by about two meters during the initial filling of the dam, which is estimated to begin around May 2014. If current plans to create new plantations continue to move forward, the lake could drop as much as 16 to 22 meters. The average depth of the lake is just 31 meters.

The river flow past the Gibe III will be almost completely blocked beginning in 2014. According to government documents, it will take up to three years to fill the reservoir, during which the Omo River’s annual flow could drop by as much as 70 percent. After this initial shock, regular dam operations will further devastate ecosystems and local livelihoods. Changes to the river’s flooding regime will harm agricultural yields, prevent the replenishment of important grazing areas, and reduce fish populations, all critical resources for livelihoods of certain indigenous groups.

The government of Ethiopia should halt development of the sugar plantations and the water offtakes until affected indigenous communities have been properly consulted and give their free, prior, and informed consent to the developments, Human Rights Watch and International Rivers said. The impact of all planned developments in the Omo/Turkana basin on indigenous people’s livelihoods should be assessed through a transparent, independent impact assessment process.

“If Ethiopia continues to bulldoze ahead with these developments, it will devastate the livelihoods of half a million people who depend on the Omo River,” said Lori Pottinger, head of International Rivers’ Ethiopia program. “It doesn’t have to be this way – Ethiopia has options for managing this river more sustainably, and pursuing developments that won’t harm the people who call this watershed home.”

Background

Ethiopia’s Lower Omo Valley is one of the most isolated and underdeveloped areas in East Africa. At least eight different groups call the Omo River Valley home and the livelihood of each of these groups is intimately tied to the Omo River and the surrounding lands. Many of the indigenous people that inhabit the valley are agro-pastoralist, growing crops along the Omo River and grazing cattle.

In 2010, Ethiopia announced plans for the construction of Africa’s tallest dam, the 1,870 megawatt Gibe III dam on the Omo River. Controversy has dogged the Gibe III dam ever since. Of all the major funders who considered the dam, only China’s Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC) provided financing (the World Bank, African Development Bank, and European Investment Bank all declined to fund it, though the World Bank and African Development Bank have financed related power lines).

The Ethiopian government announced even more ambitious plans for the region in 2011, including the development of at least 245,000 hectares of irrigated state-run sugar plantations. Downstream, the water-intensive sugar plantations, will depend on irrigation canals. Although there have been some independent assessments of the Gibe dam project and its impact on river flow and Lake Turkana, to date the Ethiopian government has not published any environmental or social impact assessments for the sugar plantations and other commercial agricultural developments in the Omo valley.

According to the regional government plan for villagization in Lower Omo, the World Bank-supported Pastoral Community Development Project (PCDP) is funding some of the infrastructure in the new villages. Despite concerns over human rights abuses associated with the villagization program that were communicated to Bank management, in December 2013 the World Bank Board approved funding of the third phase of the PCDP III. PCDP III ostensibly provides much-needed services to pastoral communities throughout Ethiopia, but according to government documents PCDP also pays for infrastructure being used in the sedentary villages that pastoralists are being moved to.

The United States Congress in January included language in the 2014 Appropriations Act that puts conditions on US development assistance in the Lower Omo Valley requiring that there should be consultation with local communities; that the assistance “supports initiatives of local communities to improve their livelihoods”; and that no activities should be supported that directly or indirectly involve forced evictions.

However other donors have not publicly raised concerns about Ethiopia’s Lower Omo development plans. Justine Greening, the British Secretary of State for International Development, in 2012 stated that her Department for International Development (DFID) was not able to “substantiate the human rights concerns” in the Lower Omo Valley despite DFID officials hearing these concerns directly from impacted communities in January 2012.

Ethiopia: Land, Water Grabs Devastate Communities | Human Rights Watch

http://www.hrw.org/news/2014/02/18/ethiopia-land-water-grabs-devastate-communities

The ‘Africa Rising’ Narrative: A Single Optimist Narrative Masks Growing Inequality in the Continent February 24, 2014

Posted by OromianEconomist in Africa, Africa Rising, Colonizing Structure, Corruption, Development, Dictatorship, Economics, Ethnic Cleansing, Food Production, Human Rights, International Economics, Land and Water Grabs in Oromia, Land Grabs in Africa, Ogaden, Omo, Omo Valley, Oromia, Oromiyaa, Oromo Identity, Oromo the Largest Nation of Africa. Human Rights violations and Genocide against the Oromo people in Ethiopia, Poverty, South Sudan, The Colonizing Structure & The Development Problems of Oromia, Tyranny, Uncategorized, Youth Unemployment.Tags: Africa, African Studies, Developing country, Development, Development and Change, Economic and Social Freedom, Economic growth, economics, Ethiopia, Gadaa System, Genocide against the Oromo, Governance issues, Horn of Africa, Human Rights and Liberties, Human rights violations, Land grabs in Africa, National Self Determination, Oromia, Oromo culture, State and Development, Sub-Saharan Africa, Tyranny, Universal Declaration of Human Rights, World Bank

add a comment

“Compare that with the mean wealth of a South African at $11,310, Libyan ($11,040) and Namibian ($10,500). While the average Ethiopian has his asset base standing at a mere $260 despite years of economic growth and foreign investment – wealth has not filtered through to the people. With this kind of glaring inequality between and within countries, the “Africa Rising” narrative risks masking the realities of millions of Africans struggling to get by in continent said to be on the move.” http://www.africareview.com//Blogs/Africa-is-rising-but-not-everywhere/-/979192/2219854/-/12at0a8/-/index.html?relative=true

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

“Africa Rising” is now a very popular story – a near-universal belief that the continent is the next investment frontier after more than a decade of sustained high growth rates and increased foreign direct investment.

We even now have memes for this new narrative.

But some people have their doubts about this whole “Afro-optimism” talk – they say Africa isn’t really rising.

They argue that Africa’s low levels of manufacturing and industrialisation discredit the continent’s “growth miracle”. Its share of world trade is remains very small compared to Asia.

Well, Africa cannot be reduced to a single narrative. We have been victims of this before – for hundreds of years the continent has always been seen in a kind of Hobbesian way – where life is poor, nasty, brutish and short.

Now, there is a minority global elite working round the clock trying to turn this long-held view of a continent.

While I do not begrudge them for their PR efforts – we cannot mask the glaring inequality in Africa by developing a new optimist narrative about the continent.

There are many stories about Africa. Not just one.

Genocide

While the sun shines bright in Namibia, not the same can be said of Malawi where the government is bankrupt or the Central African Republic (CAR) where sectarian violence is increasingly becoming genocidal.

Pretty much everyone else in the world seems accustomed to the living hell that is Somalia.

But we have also come to a consensus that Botswana and Ghana are the model countries in Africa.

South Africa is a member of the BRICS. While the petro-dollars are changing the fortunes of Angola – it has grown its wealth per capita by 527 per cent since the end of the civil war in 2002.

Not much can be said of South Sudan. Oil has not done anything despite pronouncements by the liberation leaders that independence holds much promise for the young nation’s prosperity.

The country imploded barely three years into into its independence.

This is the problem of a single narrative – it is indifferent to the growing and glaring inequality in Africa and its various political contexts.

Many Africans still have no access to the basic necessities of life. Millions go to bed without food and die from preventable diseases.

Others live in war-ravaged countries in constant fear for their lives. You can bet the last thing on their mind is not a blanket “rising” narrative about Africa and the promise it holds. That is not their Africa, its someone else’s.

Yes. “Africa Rising” may be real. But only to a small minority.

Wealth distribution

A report by New World Wealth highlights the variations in wealth distribution across the continent’s 19 wealthiest countries.

Africa’s total wealth stood at $2.7 trillion last year down from $3 trillion in 2007 after taking a hit from the global financial crisis.

These 19 countries control 76 per cent while the remaining 35 scrape over $648 billion. And most of this wealth is concentrated in northern and southern Africa.

The western, central and eastern regions have some of the poorest individuals on the continent with the highest per capita wealth from this group – with the exception of Angola – coming from Nigeria at $1,350.

Compare that with the mean wealth of a South African at $11,310, Libyan ($11,040) and Namibian ($10,500).

While the average Ethiopian has his asset base standing at a mere $260 despite years of economic growth and foreign investment – wealth has not filtered through to the people.

With this kind of glaring inequality between and within countries, the “Africa Rising” narrative risks masking the realities of millions of Africans struggling to get by in continent said to be on the move.

The sun may be shining bright in Africa – but only in favoured parts of it.

Read further @:

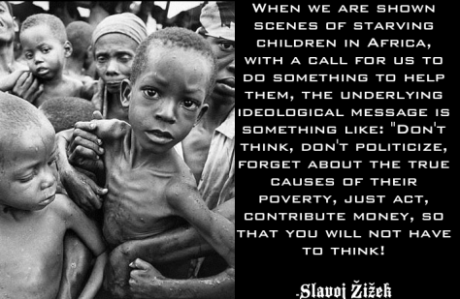

How to end poverty? February 22, 2014

Posted by OromianEconomist in Africa, Africa Rising, Colonizing Structure, Corruption, Development, Economics, Economics: Development Theory and Policy applications, Environment, Ethiopia's Colonizing Structure and the Development Problems of People of Oromia, Afar, Ogaden, Sidama, Southern Ethiopia and the Omo Valley, Ethnic Cleansing, Food Production, Janjaweed Style Liyu Police of Ethiopia, Land and Water Grabs in Oromia, Nubia, Ogaden, Omo, Omo Valley, Oromia, Oromia Support Group, Oromia Support Group Australia, Oromiyaa, Oromo, Oromo Culture, Oromo the Largest Nation of Africa. Human Rights violations and Genocide against the Oromo people in Ethiopia, Poverty, Self determination, Slavery, The Colonizing Structure & The Development Problems of Oromia, The Tyranny of Ethiopia, Tyranny, Uncategorized, Youth Unemployment.Tags: Africa, African Studies, Development, Development and Change, Economic and Social Freedom, Economic growth, Governance issues, Horn of Africa, Human Rights and Liberties, Human rights violations, Land grabs in Africa, National Self Determination, Oromia, Oromo people, Parliament, Politics of Ethiopia, poverty, Sub-Saharan Africa, Tyranny, United Nations, Universal Declaration of Human Rights, World Bank

1 comment so far

“Nations fail economically because of extractive institutions. These institutions keep poor countries poor and prevent them from embarking on a path to economic growth. This is true today in Africa, in South America, in Asia, in the Middle East and in some ex-Soviet Union nations. While having very different histories, languages and cultures, poor countries in these regions have similar extractive institutions designed by their elites for enriching themselves and perpetuating their power at the expense of the vast majority of the people on those societies. No meaningful change can be expected in those places until the exclusive extractive institutions, causing the problems in the first place, will become more inclusive.” http://otrazhenie.wordpress.com/2014/02/16/how-to-end-poverty/#

“If we are to build grassroots respect for the institutions and processes that constitute democracy,” Mo Ibrahim writes for Project Syndicate, “the state must treat its citizens as real citizens, rather than as subjects. We cannot expect loyalty to an unjust regime. The state and its elites must be subject, in theory and in practice, to the same laws that its poorest citizens are.” http://www.huffingtonpost.com/dr-mo-ibrahim/africa-needs-rule-of-law_b_4810286.html?utm_hp_ref=tw

I was always wondering about the most effective way to help move billions of people from the rut of poverty to prosperity. More philanthropy from the wealthy nations of the West? As J.W. Smith points it, with the record of corruption within impoverished countries, people will question giving them money as such ‘donations’ rarely ‘reach the target’. Building industries instead? While that approach seems to provide better results (see few examples described by Ray Avery in his book ‘Rabel with a cause‘), it still did not provide a silver bullet solution, as it does not address the roots of poverty and prosperity.

From Christian Bowe

In their book ‘Why nations fail?‘, that examines the origin of poverty and prosperity, Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson conclusively show that it is man-made political and economic institutions that underlie economic success (or the lack of it). Therefore only the development of inclusive…

View original post 844 more words

Why States Commit Genocide February 22, 2014

Posted by OromianEconomist in Colonizing Structure, Dictatorship, Ethiopia's Colonizing Structure and the Development Problems of People of Oromia, Afar, Ogaden, Sidama, Southern Ethiopia and the Omo Valley, Ethnic Cleansing, Human Rights, Janjaweed Style Liyu Police of Ethiopia, Land Grabs in Africa, Nubia, Ogaden, Omo, Omo Valley, Oromia, Oromia Support Group, Oromia Support Group Australia, Oromiyaa, Oromo, Oromo Identity, Oromo the Largest Nation of Africa. Human Rights violations and Genocide against the Oromo people in Ethiopia, Self determination, Sidama, State of Oromia, The Colonizing Structure & The Development Problems of Oromia, Uncategorized.Tags: Africa, African Studies, Developing country, Genocide, Genocide against the Oromo, Governance issues, Human rights violations, National Self Determination, Oromia, Oromiyaa, Oromo, Sub-Saharan Africa, Tyranny, United Nations, Universal Declaration of Human Rights, World Bank

1 comment so far

It wasn’t always like this. Before nationalism, empires frequently ruled territory that contained many diverse peoples. The Habsburg family once ruled over the Spanish, Dutch and Austrian nations, along with many of the nations of Latin America. The Romans ruled hundreds of peoples great and small, from Greeks to Gauls to Britons to Iberians to Gallicians to Egyptians to Thracians to Illyrians to Carthaginians to Numidians and on and on. Before nationalism, peoples would rather submit to foreign conquerors than risk the loss of life and limb, and as a result conquerors rarely engaged in genocide except as a means of exacting vengeance on foreign rulers who defied them (as the Mongols and Assyrians were wont to do). Empires often took some of the vanquished as slaves, but rarely did empires kill thousands or millions of defenseless people deliberately and systematically for the sole purpose of decimating another nation. Instead, empires often brought conquered peoples into their trade networks, recruited them into their armies, and, eventually, even granted them citizenship rights. By treating conquered people well, they could in time acquire their loyalty.

Nationalism changed all of that. By placing lexical priority on independence and self-determination, all foreign occupiers become villains regardless of whether they are benign or malevolent in their treatment of the occupied nation. In this day and age, even members of a nation like the Scots, which enjoys spectacularly generous subsidies and full voting rights from the British government in Westminster, desire independence purely on the basis that some Scots are nationalists and believe that nothing less than full self-determination does their nation justice. If good treatment doesn’t buy loyalty, occupiers quickly find that they are without incentives to treat subject peoples well or to attempt to integrate them into their states. Nationalism becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy–if occupiers have nothing to gain by offering fair terms of cooperation, they will not offer them, and the subjugation nationalists fear becomes reality precisely because they fear it and refuse to cooperate with the occupier.

The occupier is left with two choices:

Get Out.

Kill Them All.

Often times, occupiers choose to abandon whatever ambitions they might have had and leave in defeat and disgrace. But this doesn’t always happen–some leaders correctly reason that if they could just replace the existing population with their own people, they could pacify the territory and keep the resources it provides. If those leaders have the stomach for it, they will do the following:

Systematically murder the resisting nation.

Colonize the extinct nation’s territory with their own citizens.

Profit.

If we want to prevent genocide, we need to prevent occupiers from having to choose between defeat and genocide.

Why States Commit Genocide

by Benjamin Studebaker

http://benjaminstudebaker.com/2014/02/21/why-states-commit-genocide/

Africa Must Industrialize: The Time IS Now February 20, 2014

Posted by OromianEconomist in Africa, Africa Rising, African Poor, Agriculture, Aid to Africa, Development, Economics, Economics: Development Theory and Policy applications, Environment, Food Production, Oromo, The Colonizing Structure & The Development Problems of Oromia, Uncategorized, Youth Unemployment.Tags: Africa, African culture, African Studies, Developing country, Development and Change, Economic and Social Freedom, Economic development, Economic growth, economics, Horn of Africa, Human rights violations, Land grabs in Africa, National Self Determination, Oromia, Oromiyaa, Oromo, Social Sciences, Sub-Saharan Africa, United Nations, Universal Declaration of Human Rights, World Bank

add a comment

As the current economic growth did not result from value addition and increased manufacturing, but instead from increases in world commodity prices, it makes the region susceptible to commodity price volatility. If commodity prices fall, Africa’s impressive economic growth might grind to a halt — thus, the dire need for diversification through industrialization. Even if commodity prices stay high, natural resources are not infinite and they must be managed with sagacity.

As recommended by the 2013 Africa Progress report, it is advantageous for African governments to fully implement the Accelerated Industrial Development for Africa (AIDA) plan, signed in 2008 in Addis-Ababa. The AIDA is a comprehensive framework for achieving the industrialization of the continent. If Africa can successfully steward its natural resource wealth, investing it wisely and using some to industrialize, then whether the resources run out or not or whether commodity prices fall, Africa would be on a good economic footing.

Moreover, not only will industrialization create the environment for adding value to Africa’s natural resources, but it will also provide much needed employment at various stages of the value adding chain for Africa’s 1.1 billion people — leading to wealth creation.

Industrialization will address many development gaps in sub-Saharan Africa. Some of these gaps, as noted in a UNECA Southern Africa Office Expert Group Meeting Report, include:

Africa’s high dependence on primary products

Low value addition to commodities before exports

High infrastructure deficit

High exposure to commodity price volatility

Limited linkage of the commodities sector to the local economy

Poorly developed private sector, which is highly undercapitalized

Limited commitment to implement industrial policies

Limited investment in R&D, science, innovation and technology

Low intra-Africa trade

Slow progress towards strengthening regional integration

The Time is Now

Is Africa ready? The answer is an emphatic yes. The phenomenal growth is one reason why Africa is ready, but growth on its own is not enough. Other conditions need to be considered: Does the continent have access to enough raw materials for production? What is the proximity of these natural resources to the continent? Is there adequate land, labor, and capital? These are the traditional factors of production or inputs to the production process.

Yes, Africa has access to the raw materials necessary for production. Unlike already industrialized nations who have to import raw materials from Africa and elsewhere over long distances, Africa enjoys close proximity to these resources.

With regards to the factors of production, Africa is the world’s second largest continent and therefore is home to plenty of land — most of which is arable.

Africa is also the world’s second most populous continent. The average age of an African in Africa is under 19 years. This means Africa has enough manpower or labor to industrialize.

Capital refers to man-made products used in the production process such as buildings, machinery and tools. Africa does have a measure of this, but instead needs to do more in this area — hence the need for greater infrastructural and skills development. In fact, African policymakers as well as their counterparts in the developed world should realize that it is high time for a shift in the nature of aid to the continent — from primarily monetary aid to the type of capital aid needed for industrialization.

Finally, when Africa successfully undergoes industrial development, its huge populace will serve as a market for the outputs of its production processes; any excess supply can be exported and swapped for foreign exchange. Africa is ready and the time for it to industrialize is now.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

read more@

Dependency Aid is Dysfunctional: Time for Self-sufficiency February 19, 2014

Posted by OromianEconomist in Africa, Africa Rising, Agriculture, Aid to Africa, Development, Economics, Economics: Development Theory and Policy applications, Food Production, The Colonizing Structure & The Development Problems of Oromia, Uncategorized.Tags: Africa, African culture, African Studies, Aid and Development, Developing country, Development, Development aid, Development and Change, Economic and Social Freedom, Land grabbing, Oromia, Social Sciences, Sub-Saharan Africa, United Nations, Universal Declaration of Human Rights, World Bank

add a comment

Against the dysfunctional dependency foreign assistance, Clare Lockhart in World Affairs argues for cheaper, smarter and stronger aid that creates self-sufficiency.

‘Commerce [and] entrepreneurial capitalism take more people out of poverty than aid . . . . It’s not just aid, it’s trade, investment, social enterprise. It’s working with the citizenry so that they can unlock their own domestic resources so that they can do it for themselves. Think anyone in Africa likes aid? Come on.’

Putting these “Fish for a Lifetime” approaches into effect will require some major shifts. It will involve looking not to how much money was disbursed, or how many schools were built, but to value for money and return on investment. And instead of propping up a vast technical assistance industry of varying and often indifferent quality, a higher priority will be placed on conducting a “skills audit” of key personnel—from doctors and teachers to engineers and agronomists—who can be trained internally rather than importing more costly and less invested technical assistance from abroad.

‘It is also important under this new paradigm to distinguish between “aid” (such as life-saving humanitarian assistance and the financial or material donations it requires) and “development engagement,” which is something quite different. Development engagement can be low-budget, and should be designed to move a needy country toward self-sufficiency—so that the state can collect its own revenues and the people can support their own livelihoods—as soon as possible. Many recipient countries have enormous untapped domestic resources, and with some effort devoted to increasing those revenues and building the systems to spend them, could assume much more of the responsibility of meeting their citizens’ needs.’

But a strategy is only as good as its execution. Implementing development policies and programs correctly will require a clear-eyed look at the way programs are designed and implemented, and a re-examination of the reliance on contractors. There is no substitute in the long term for unleashing a society’s domestic potential of human, institutional, and natural capital through a well governed country.

‘Having judged the development programs of the last decade to be failures, many in the US now call for development budget cuts and wearily espouse isolationism. But it is a classic example of throwing the baby out with the bathwater. Failed methods do not mean that the goal of international development must be abandoned. Development needn’t be an indulgent venture in charity, or risky business, or a road to nowhere paved with good intentions. A more hardheaded approach, one that creates self-sufficiency rather than dependency, is the new beginning that the development world has been waiting for.’ – http://www.worldaffairsjournal.org/article/fixing-us-foreign-assistance-cheaper-smarter-stronger

In 2002, during the early stages of Afghanistan’s reconstruction process, I sat in a remote part of Bamiyan Province with a group of villagers who told me how excited they had been several months before, when a $150 million housing program from a UN agency had been announced on the radio. They felt the program, which promised to bring shelter to their communities, would transform their lives. They were shocked, however, to discover soon after that this program had already come and gone—with very little change to their lives. Indignant, as well as curious, they decided to track the money and find out what had happened to the program that, as far as they were concerned, had never been. Becoming forensic accountants, they went over the files and figures and found that the original amount granted by the UN had first gone through an aid agency in Geneva that took twenty percent off the top before sub-contracting to a Washington-based agency that took another twenty percent. The funds were passed like a parcel from agency to agency, NGO to NGO, until they limped to their final destination—Afghanistan itself. The few remaining funds went to buy wood from Iran, shipped via a trucking cartel at above-market rates. Eventually some wooden beams did reach the village, but they were too heavy for the mud walls used in construction there. All the villagers said they could do was cut up the wood for firewood, sending $150 million literally up in smoke.

With examples like this, it’s really no surprise that a growing chorus of commentators claims that foreign development is expensive, ineffective, and often resented by the intended beneficiaries. In The White Man’s Burden, for instance, William Easterly provides a searing critique of this do-good mentality, which he shows often causes more harm than help. In The Crisis Caravan, Linda Polman documents the unintended consequences of humanitarian assistance. In Dead Aid, Dambisa Moyo argues that aid serves to fuel corruption and lack of accountability among elites.

Critics of US assistance build on this narrative to paint a picture of an America overstretched and in decline, wasting money abroad in a futile effort to serve its uncertain foreign policy objectives, and call for cutbacks and disengagement.

The US has spent $100 billion in nonmilitary funds to rebuild Afghanistan. Yet, after a decade of mind-bending mismanagement and unaccountability, it seems all for naught.

Some of America’s recent engagements abroad have indeed been marked by extraordinary waste and poor design. As Joel Brinkley described in an article in this publication one year ago (“Money Pit,” January/February 2013), American aid to Afghanistan has at times been extravagantly wasteful, as when a contractor overbilled the US government by $500 million. Brinkley also points to the general practice of outsourcing aid projects to contractors with little oversight. Such failures undermine confidence in the very notion of US efforts in confronting poverty and call into question our ability to deal with conflict through “soft power.”

But this criticism misses an important distinction: it is not the principle of engagement, but the way many development projects work that has led to failure. There is, in fact, an alternative way of engaging abroad to promote stability and prosperity with more lasting effect and at a far lower cost than what has become a discredited status quo.

This alternative approach recognizes that there is no shortcut to development that circumvents the citizens and governing institutions of the country. It recognizes the prominent role of entrepreneurial and civic activity. It demonstrates an understanding that institutional change requires years, not months. It has been practiced by a number of farsighted development programs that have reinforced principles of partnership and local ownership of the policy agenda. This “Learn to Fish for a Lifetime” model seeks to build up local institutions that provide security, good governance, and other elements of self-sustaining economic growth. It takes advantage of the things that America knows how to do well: mobilizing investors, firms, universities, and other potent but underused tools that leverage private capital to deliver a kind of development that far outlasts the initial intervention. Many of the activities undertaken with this model actually generate enough revenue to pay back the initial investment, meaning that foreign development projects could someday operate at or close to “net zero” expenditure to the US taxpayer, a particularly appealing prescription in an era of harsh fiscal realities.

Putting “Fish for a Lifetime” approaches into practice, however, requires rejecting the prevailing approach, which makes for a complicated and ultimately self-defeating operation, in favor of one that emphasizes return on investment, both financially and in terms of improved conditions on the ground.

My own wake-up call to the yawning gap between the intentions and impact of major development programs came in that remote part of Afghanistan, soon after the Taliban had fled. Stories similar to the one I heard have been documented by the US special inspectors general for Iraq and Afghanistan reconstruction. But it is not just in combat zones where billions of taxpayers’ funds have created disappointment. After Haiti’s tragic earthquake in January 2010, world powers promised to “build back better” and citizens internationally joined them in committing billions of dollars to that country’s reconstruction. Aid programs in Haiti were notoriously dysfunctional even before the earthquake, but in the scramble to provide help after the catastrophe, funds and opportunities were squandered on an even grander scale. More than three years on, results have fallen far short of the promise. It is what one commentator and Haiti expert, Jonathan Katz, bleakly referred to in the title of his book on the aftermath of the earthquake: The Big Truck That Went By: How the World Came to Save Haiti and Left Behind a Disaster.

Haitian President Michel Martelly has been vocal in his criticisms of the effort, too: “Where has the money given to Haiti after the earthquake gone? . . . Most of the aid was used by nongovernmental organizations for emergency operations, not for the reconstruction of Haiti . . . . Let’s look this square in the eye so we can implement a better system that yields results.”

As Mark Schuller documents in his book Killing with Kindness, foreign donors directed the money to a network of NGOs that bypassed the Haitian government’s policy framework and the implementation capacity of its private sector, and thereby failed to meet the priorities of its citizens. Haitian organizations saw very little of the investment they needed to rebuild their society, but instead were overwhelmed by a vast aid machinery that parachuted down upon them with its own rules and priorities and complex bureaucracy.

Failure, as Haiti showed, does not come from a shortage of money or goodwill. Rather, the aid business has been afflicted by a set of institutional pathologies that almost guarantee failure. Projects designed in national capitals and foreign embassies are often divorced from the realities of the local lives of the people they intend to help, while the long time frames and rigidity of design mean that by the time a project rolls out, it is often irrelevant, even if money actually arrives after the overhead is paid to the food chain of delivery organizations. Multiple contractual layers mean too much of the original project money never even leaves international capital regions—especially Washington.

In Banda Aceh, Indonesia, analysts report how an NGO spent nearly $1 million of European Commission money on a project to construct eleven boatyards intended to stimulate the livelihoods of local fishermen, but in the end only created ten boats, none of them seaworthy.

Somewhere along the way, incentives have become skewed. Project managers and contractors alike are monitored mainly for whether the money in their charge can be tracked, rather than for whether aid activities have any transformational power. For many aid agencies, moreover, running projects has become the goal, rather than seeking to foster institutions and build productive partnerships among governments, firms, and communities. The metrics track whether a project was completed and the money disbursed, not whether sustainable institutions were left after the money had come and gone.

Finally, much of what has become standard procedure in the development business distorts local markets and displaces market activity. Every time a wheat consignment is distributed for free, for instance, local farmers see the market price for their locally grown wheat decrease. In Afghanistan in 2003, after a large-scale World Food Program wheat distribution, farmers threw up their hands and simply let their crops rot because aid had collapsed the market. Nor is it only farmers who are affected by thoughtless charity. Every time solar panels, water pumps, tractors, or cell phones are handed out for free, a local supplier can no longer sell and install his inventory, and a small business that might have long-range prospects for hiring and supporting several people is smothered.

The perversity of incentives operating in the aid and development field is no longer a trade secret. It has caught the attention of even some of the founders of the modern aid movement. “Aid is just a stopgap,” the pop star Bono, one of the forces behind putting charity to Africa on the map through the Live Aid concerts, told an audience at Georgetown University in November 2012. “Commerce [and] entrepreneurial capitalism take more people out of poverty than aid . . . . It’s not just aid, it’s trade, investment, social enterprise. It’s working with the citizenry so that they can unlock their own domestic resources so that they can do it for themselves. Think anyone in Africa likes aid? Come on.”

In an apparent one-eighty from his earlier focus on simply mobilizing aid donations, Bono’s Live Aid partner, Sir Bob Geldof, has followed suit by launching an infrastructure investment firm for Africa, proclaiming, “I want to leave behind me firms, farms, and factories.”

While the stories of what didn’t work in Afghanistan have grabbed the headlines, there have also been several examples of successful development engagement there. The National Solidarity Program in Afghanistan, for example, has directly reached more than thirty-eight thousand villages since 2003. Under its approach, a block grant, ranging from $20,000 to $60,000, goes directly to a bank account held by the village council, or Community Development Council. The village doesn’t have to apply for the funds, but if it wants to, it must follow three simple rules: elect or appoint the council, ensure a quorum of residents attend meetings to choose projects, and post the accounts in a public place. To date, the program has disbursed more than $1.6 billion, and the village councils have completed more than seventy thousand projects—roads to the local markets, water canals, and generators and microhydro systems that electrify the area.

In one case, thirty-seven villages trying to combat the loss of women in childbirth got together and pooled their money to build a maternity hospital. In another case, one hundred and eighty-five villages pooled their money to create a watershed management system, vastly expanding the land they could cultivate. NGOs are involved in these projects as facilitators who support the village through the complex transactions that it must undertake, but unlike in the traditional model of development, they don’t hold the purse strings or oversee the implementation of projects. The US Agency for International Development is now part of an international consortium that contributes to the program costs.

Similar projects exist at even greater scale in Indonesia and Pakistan. In Indonesia, the National Program for Community Empowerment (PNPM) works in more than eighty thousand villages across the nation. The program formed in 1998, in the wake of the Asian financial crisis, with the imperative to benefit communities directly with cash. Neither the government’s social safety nets nor the NGOs could do this alone, and so a partnership between governments and communities was established. Over time, the program has evolved to include micro-finance and other investment facilities, barefoot lawyers programs, and the construction of schools—all managed directly by the villages themselves.

According to official numbers, one of the PNPM programs, PNPM Mandiri Rural, reached four thousand three hundred and seventy-one sub-districts by 2009, and saw the construction or rehabilitation of ten thousand kilometers of road, two thousand and six bridges, two thousand nine hundred and eighty-six health facilities, and three thousand three hundred and seventy-two schools, in addition to the construction of public sanitation facilities and irrigation systems. These projects increased per capita consumption gains by eleven percent and reduced unemployment by one and a half percent. PNPM can accomplish all of this because of an open planning process by which projects are targeted to meet demand as expressed by the community rather than by officials thousands of miles away.

In a similar operation in Pakistan, the Rural Support Programs Network (RSPN) partners with three hundred and twenty thousand community organizations, covering five million households and thirty-three million people. These organizations have led responses to the earthquakes and floods, organized micro-finance and health insurance schemes, and built and operated schools, clinics, roads, and hydropower schemes.

This family of homegrown programs in Afghanistan, Indonesia, and Pakistan, and similar ones in Colombia, Mexico, and India, have proven it is possible to reach communities directly and at scale, cutting out the layers of contractors and NGOs that function as middlemen, while making communities the implementers of their own development in projects that achieve real results.

We really don’t need to look far afield to find approaches that work. There are a number of distinctly American approaches to development that have delivered in the past but have fallen unaccountably into disuse. Take the Economic Cooperation Act of 1948, a framework that for a while worked exceptionally well, but whose practices have been strangely forgotten in recent decades. At its core was the idea of facilitating “the achievement by the countries . . . of a healthy economy independent of extraordinary outside assistance.” The act’s programs, including the tremendously successful Marshall Plan, were geared toward the institutional and economic self-sufficiency of the recipients, with a central premise that the program could be judged a success only if it reduced the need for aid, rather than perpetuating it.

The Marshall Plan worked for the countries it sought to benefit and worked for the donor as well, paying the US back dividends both economically and in security terms far above its costs. This did not happen by chance. One of the participants in this plan, the political scientist Herbert Simon, describes in Administrative Behavior the painstaking organizational design that went into fine-tuning its approach. George Kennan, in a now-declassified memo from 1947, argued that “it is absolutely essential that people in Europe should make the effort to think out their problems and should have forced upon them a sense of direct responsibility for the way the funds are expended. Similarly, it is important that people in this country should feel that a genuine effort has been made to achieve soundness of concept in the way United States funds are to be spent.”

Other lesser-known US development programs similarly brought impressive results with moderate or no cost to the US taxpayer.

In the aftermath of the Korean War, South Korea had one of the lowest GDPs on earth, but between 1966 and 1989, it raised its GDP by an average of eight percent per year. Behind this story lies a dedicated effort to foster local capacity and industrial-led growth, backed by a US partnership. In 1966, President Lyndon Johnson agreed with President Park Chung-hee of South Korea to help establish the Korea Institute of Science and Technology (KIST) and assembled a team of leading scientists and technical experts to form and plan the institute. KIST aimed to nurture Korea’s own technical and managerial capacity to lay the basis for its economic transformation, rather than remain dependent on foreign management and input for its projects and companies. Korea is now one of a handful of nations that combine GDP per capita in excess of $20,000 with a population of more than fifty million people.

The South Korean government and the US government each contributed $10 million to KIST at its founding, and Washington used a similar model when it helped establish the Saudi Arabian National Center for Science and Technology (SANCST) in 1977. Saudi funds went to the US Treasury, which in turn paid for the technical assistance required for the center and a range of other initiatives.

Many of the best development initiatives are not directed by governments, but by the private sector and its use of market mechanisms. One example is the involvement of the Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC) in the Afghan telecom sector. In 2002, Afghanistan had sparse telephone coverage, with access only either through a small number of fixed lines or very expensive satellite coverage. The UN proposed that the telecom sector should be addressed through an aid-driven approach, whereby funds would be used to contract with a major cell phone provider to set up services that would provide coverage to key embassies and aid agencies, at an estimated cost in the tens of millions of dollars. But, in line with how cell phone services are organized in any developed country, it was decided instead that rather than being paid by the government or aid agencies, the telephone company would bid for the license to operate a commercial service, with the proviso that services include a certain level of coverage and standard of quality.

The tender process went ahead. Several international companies registered their interest, but many expressed reservations about the level of risk they would be undertaking. This is where OPIC stepped in to draw up a risk guarantee for possible political and security problems. With an expenditure of just $20 million, this agreement provided sufficient confidence in the telecom sector for investment to proceed. By now, several billion dollars have been invested, more than sixteen million phones purchased, significant revenues generated via taxes to the Afghan government—and the $20 million guarantee was never called upon because the risks feared by the private companies never materialized. In this case, a risk instrument was able to pave the way for new market opportunities and to provide an essential service. Contrast that with the typical aid approach, which would have distorted the market, squandered money, and likely produced, at best, ambiguous results.

A similar example came out of the Caribbean. Before 2007, individual insurance companies were reluctant to insure Caribbean islands for hurricane and earthquake damage, the liability being considered commercially too risky. But then the World Bank’s Caribbean Catastrophe Risk Insurance Facility (CCRIF) was created, pooling risk to enable governments in the area to purchase affordable insurance. CCRIF was designed to protect Caribbean countries from the financial fallout of a natural disaster, offering each country timely and flexible payouts. The group can respond more quickly and more efficiently to a member country in need than can the sort of chaos of good intentions that descended on Haiti, as was demonstrated in its response to Hurricane Tomas in 2010. Barbados, St. Lucia, and St. Vincent and the Grenadines received fifty percent of their payouts within days.

In contrast to a top-down, statist aid paradigm, these “Fish for a Lifetime” approaches are all designed to unlock and leverage the value from within the society, state, and market. They all start with the operating principle of co-designing programs with the citizens and leaders from the country concerned. Where there is a market, they do not seek to use grant capital. Once the initial intervention is over, success is judged by whether or not the innovations designed for the crisis are sustainable. This approach is geared toward increasing the self-sufficiency of the country concerned, and in particular boosting its economy and generating its own revenue and tax base.

While the treasuries of most Western countries may be afflicted by the constraints of austerity budgeting, there are vast amounts of private investment capital looking for opportunities. Many of the countries that are seen as the neediest destinations for aid are also considered by emerging market investors as the fastest-growing in the world—Rwanda, Nepal, Indonesia, and India. Infrastructure projects from power to roads and ports can and do attract private capital, and public funds can be used for risk guarantees or as co-investments rather than grant aid for these projects. Rather than seeking to maximize aid, such an approach seeks to maximize the return on investment to the society concerned.

Putting these “Fish for a Lifetime” approaches into effect will require some major shifts. It will involve looking not to how much money was disbursed, or how many schools were built, but to value for money and return on investment. And instead of propping up a vast technical assistance industry of varying and often indifferent quality, a higher priority will be placed on conducting a “skills audit” of key personnel—from doctors and teachers to engineers and agronomists—who can be trained internally rather than importing more costly and less invested technical assistance from abroad.

It is also important under this new paradigm to distinguish between “aid” (such as life-saving humanitarian assistance and the financial or material donations it requires) and “development engagement,” which is something quite different. Development engagement can be low-budget, and should be designed to move a needy country toward self-sufficiency—so that the state can collect its own revenues and the people can support their own livelihoods—as soon as possible. Many recipient countries have enormous untapped domestic resources, and with some effort devoted to increasing those revenues and building the systems to spend them, could assume much more of the responsibility of meeting their citizens’ needs. Getting the toolbox right requires instruments that can best support this approach: the OPIC, enterprise funds, chambers of commerce, public diplomacy, scholarships, international financial institutions, trade measures, and the National Academies, among others.

But a strategy is only as good as its execution. Implementing development policies and programs correctly will require a clear-eyed look at the way programs are designed and implemented, and a re-examination of the reliance on contractors. There is no substitute in the long term for unleashing a society’s domestic potential of human, institutional, and natural capital through a well governed country.

Having judged the development programs of the last decade to be failures, many in the US now call for development budget cuts and wearily espouse isolationism. But it is a classic example of throwing the baby out with the bathwater. Failed methods do not mean that the goal of international development must be abandoned. Development needn’t be an indulgent venture in charity, or risky business, or a road to nowhere paved with good intentions. A more hardheaded approach, one that creates self-sufficiency rather than dependency, is the new beginning that the development world has been waiting for.

Clare Lockhart is the coauthor, with Ashraf Ghani, of Fixing Failed States and the director of the Institute for State Effectiveness, an organization devoted to finding, documenting, and facilitating better approaches to engaging abroad.

Read further at original source:

http://www.worldaffairsjournal.org/article/fixing-us-foreign-assistance-cheaper-smarter-stronger

Africa: Agribusiness Feeds the Rich; Small Farmers Feed the Rest February 18, 2014

Posted by OromianEconomist in Africa, Africa Rising, African Poor, Agriculture, Aid to Africa, Climate Change, Colonizing Structure, Corruption, Development, Domestic Workers, Economics: Development Theory and Policy applications, Environment, Ethnic Cleansing, Food Production, Human Rights, Knowledge and the Colonizing Structure. African Heritage. The Genocide Against Oromo Nation, Land Grabs in Africa, Ogaden, Omo, Oromia, Oromiyaa, Oromo, Oromo Nation, Oromo the Largest Nation of Africa. Human Rights violations and Genocide against the Oromo people in Ethiopia, Self determination, Slavery, State of Oromia, The Colonizing Structure & The Development Problems of Oromia, The Tyranny of Ethiopia, Uncategorized, Youth Unemployment.Tags: Africa, African culture, African Studies, Developing country, Development, Development and Change, Economic and Social Freedom, Economic development, Economic growth, Family Farm in Africa, Industrial Agriculture, Land grabbing, Land grabs in Africa, Oromo, Oromo people, Small Farm, Sub-Saharan Africa, Tyranny, World Bank

add a comment

“Agribusiness feeds the rich; small farmers feed the rest. Yet we have a strong interest in feeding the world and are concerned that food conferences dominated by agribusiness directly threaten our ability to produce affordable, healthy, local food.Solving world hunger is not about industrial agriculture producing more food – our global experience of the green revolution has shown that the drive towards this industrial model has only increased the gap between the rich and the poor. Feeding the world is about increasing access to resources like land and water, so that people have the means to feed themselves, their families and their communities. Small family farms produce the majority of food on the planet – 70% of the world’s food supply! If conferences, like this one, exclude the voice of small farmers, then the debate about feeding the world is dominated by the rich and the solutions proposed will only feed their profits.”

A farming revolution is under way in Africa, pushed by giant corporations and the UK’s aid budget. It will surely be good for the global economy, writes Sophie Morlin-Yron, but will Africa’s small farmers see the benefit?

Many millions of small farmers that were once merely poor, will be propelled into destitution, the chaff of a neoliberal market revolution as pitiless as it is powerful.

World leaders in agriculture and development gathered in London last week at the The Economist’s ‘Feeding the World Summit’ to discuss global solutions to tackling Africa’s food security crisis.

At the event, which cost between £700 and £1,000 to attend, industry leaders spoke of new innovations and initiatives which would help fight poverty, world hunger and malnutrition, and transform the lives of millions of farmers worldwide.

Just one farmer

But there was only one farmer among the speakers, Rose Adongo, with barely a handful more in the audience. A Ugandan beef and honey farmer, Adongo was unimpressed by the technical solutions offered by the corporate speakers.

For her, the main issue was land ownership for farmers – and desperately needed changes in Ugandan law, under which women have no right to land ownership even though 80% of the country’s farmers are women, and they produce 60% of the food.

If only a woman could own land – currently passed down from father to son “she can produce more food”. Besides that she wanted cheaper fertilisers and an end to the desperate toil of hand working in the fields. Much of the land is currently plowed by hand which “can take weeks to do”.

Among the excluded …

But many were excluded from the event – and desperately wanted their voices to be heard. Among them was Jyoti Fernandes, from The Landworkers’ Alliance (member of La Via Campesina), a producer-led organisation representing small-scale agroecological producers in the UK.

“Agribusiness feeds the rich; small farmers feed the rest”, she said. “None of our members could afford to attend the Feeding the World Summit.

“Yet we have a strong interest in feeding the world and are concerned that food conferences dominated by agribusiness directly threaten our ability to produce affordable, healthy, local food.

Solving world hunger, she insisted, “is not about industrial agriculture producing more food – our global experience of the green revolution has shown that the drive towards this industrial model has only increased the gap between the rich and the poor.”

Improving access to land and water

“Feeding the world is about increasing access to resources like land and water, so that people have the means to feed themselves, their families and their communities.

“Small family farms produce the majority of food on the planet – 70% of the world’s food supply! If conferences, like this one, exclude the voice of small farmers, then the debate about feeding the world is dominated by the rich and the solutions proposed will only feed their profits.”

As Graciela Romero of War on Want commented in The Ecologist last week, it is that small farmers are feeding the world – not corporations:

“Millions of small-scale farmers produce 70% of the world’s food. Yet they remain excluded and forgotten from exchanges which affect their livelihoods or concern how to end world hunger.”

Private investment

Among the 27 speakers at the event were Nestlé Head of Agriculture Hans Joehr, Monsanto CEO Hugh Grant, Cargill Vice-Chairman Paul Conway, UN Secretary General for Food Security and Nutrition David Nabarro, and representatives from the World Food Program and World Vision.

And despite the involvement of some NGOs, academics UN officials, the main topic of discussion was private sector investment in agriculture.

Lynne Featherstone, a junior UK minister for International Development, said the way forward is newly developed efficient fertilisers, pest tolerant crops and private sector investment:

“There is substantial room for improvement, and helping farmers increase productivity while consuming fewer inputs is a priority. With partners such as CGIAR we have developed more efficient fertilisers and pest tolerant crop varieties.”

UK spending £280m to support private sector engagement

She also outlined the Government plans to invest £280m from its aid budget funding in businesses and organisations under the Alliance for Food Security and Nutrition (AFNC).

This private sector initiative – which has also involves 14 Governments – ostensibly aims to lift 50 million people in Africa out of poverty by 2022, by attracting more private investment in agriculture. Featherstone explained the rationale:

“Economic growth in these countries is best achieved through agricultural growth, which has the power of raising incomes and getting people out of poverty. And the private sector can catalyse that agricultural growth with sustainable agricultural investment.”

But is it really about land grabs?

But critics fear that is has rather more to do with getting governments on-side so corporations can carry out land grabs – taking the best watered and most fertile land away from African farmers and delivering it up to investors to plant cash crops across the continent, while turning once independent small farmers into a a proletarian underclass of landless plantation workers and rootless urban workers.

Paulus Verschuren, Special Envoy on Food and Nutrition Security, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, The Netherlands attempted to strike a balance:

“We are not going to fix the zero-hunger challenge without involving the private sector, but we need to set the criteria for these transformational partnerships. They need to have a business outcome and a development outcome.”

Corporations keen to help small farmers …

Representatives of major food corporations also insisted that they wanted to work with small farmers and help them to produce their crops efficiently while meeting development objectives.

Nestlé’s Corporate Head of Agriculture, Hans Jöhr, claimed to be willing to work with small farmers as well as large to fulfil development objectives and improving resource efficiency:

“The issue of feeding the world has to been seen in perspective of rural development, and not only technology”, he said. “And it’s definitely not about talking small versus big farmers, I think that was really the yesterday talk. It’s about people, individuals, it’s about farmers.

We cannot go on polluting and destroying

“So in this meeting about farmers, when we are talking about farmers, we are going back to what we have listened to, the restrictions we all face in business is natural resources, natural capital. It’s not only about the land, it’s mainly about water.

“This leads us to looking into production systems and methods and understanding that we cannot continue to go on with polluting destroying and depleting natural resources and with wasting them.

“Farmers who don’t know how to farm waste a tremendous amount of natural resources and agricultural materials because they don’t know how to store, and are not linked to an outlet to markets. That means that we have to help them better understand the production systems.”

Productivity must be raised

Vice Chairman of Cargill, Paul Conway, emphasised the importance of secure land ownership: “The number one thing here isn’t technology, it isn’t finance, it’s security of tenure of the land, which is absolutely critical.”

And Monsanto’s CEO Hugh Grant played down the importance of genetic modification in improving crop yields in Africa, from 20 bushels of grain per hectare to India’s typical level of 100 bushels.

“There is no reason Africa shouldn’t be close to India, it’s all small-holder agriculture. Why is it 20 today and not 90? Now forget biotech, that’s eminently achievable with some sensible husbandry and land reform ownership, the tools are in hand today.”

“We have set goals to double yields in the next 30 years with a third less water, agriculture gets through an enormous amount of water. The first 70 per cent of which goes to agriculture, the next 30 per cent goes to Coke, Pepsi, swimming pools and everything you drink and all of industry, and that isn’t sustainable.

We believe our sole focus on agriculture is vital as the world looks to produce enough nutritious food to feed a growing population while conserving, or even decreasing, the use of precious natural inputs such as land, water and energy.”

Farmers ‘invisible and irrelevant’

But Mariam Mayet, Director of African Safety for Biosafety – which campaigns against genetic engineering, privatisation, industrialisation and private sector control of African agriculture – was not convinced.

To the constellation of famous speakers and corporate representatives, she said, small farmers were a simple obstruction to progress:

“We know that all of African farmers are invisible and irrelevant to those at this summit. These producers are seen as inefficient and backwards, and if they have any role at all, it is to be forced out of agriculture to becoming mere passive consumers of industrial food products.

“Africa is seen as a possible new frontier to make profits, with an eye on land, food and biofuels in particular.

“The recent investment wave must be understood in the context of consolidation of a global food regime dominated by large corporations in input supply such as seed and agrochemicals especially, but also increasingly in processing, storage, trading and distribution.

“Currently African food security rests fundamentally on small-scale and localised production. The majority of the African population continue to rely on agriculture as an important, if not the main, source of income and livelihoods.”

Can the chasm be bridged?

If we take the sentiments expressed by corporate bosses at face value – and why not? – then we do not see any overt determination to destroy Africa’s small farmers. On the contrary, they want to help them to farm better, more productively and efficiently, and more profitably.

And perhaps we should not be surprised. After all that suits their interests, to have a growing and prosperous farming sector in Africa that can both buy their products and produce reliable surpluses for sale on global food markets.

The rather harder question is, what about those farmers who lack the technical or entrepreneurial ability, the education, the desire, the extent of land, the security of land tenure, to join that profitable export-oriented sector? And who simply want to carry on as mainly subsistence farmers, supporting their families, producing only small surpluses for local sale?

The small subsistence farmer has no place

Stop and think about it, and the answer is obvious. They have no place in the new vision of agriculture that is sweeping across the continent, with the generous support of British aid money.

Their role in this process is to be forced off their land – whether expelled by force or by market forces – and deliver it up to their more successful neighbour, the corporation, the urban agricultural entrepreneur, to farm it at profit for the market.

And then, either to leave their village homes and join the displaced masses in Africa’s growing cities, or to stay on as landless workers, serving their new masters.

This all represents ‘economic progress’ and increases in net production. But look behind the warm words – and many millions of small farmers that were once merely poor, will be propelled into destitution, the chaff of a neoliberal market revolution as pitiless as it is powerful.

Is this really how the UK’s aid funds should be invested?

Sophie Morlin-Yron is a freelance journalist.

Oliver Tickell edits The Ecologis

http://www.theecologist.org/News/news_analysis/2287243/africas_farm_revolution_who_will_benefit.html

A landmark G8 initiative to boost agriculture and relieve poverty has been damned as a new form of colonialism after African governments agreed to change seed, land and tax laws to favour private investors over small farmers.

Ten countries made more than 200 policy commitments, including changes to laws and regulations after giant agribusinesses were granted unprecedented access to decision-makers over the past two years.

The pledges will make it easier for companies to do business in Africathrough the easing of export controls and tax laws, and through governments ringfencing huge chunks of land for investment.

The Ethiopian government has said it will “refine” its land law to encourage long-term land leases and strengthen the enforcement of commercial farm contracts. In Malawi, the government has promised to set aside 200,000 hectares of prime land for commercial investors by 2015, and in Ghana, 10,000 hectares will be made available for investment by the end of next year. In Nigeria, promises include the privatisation of power companies.

A Guardian analysis of companies’ plans under the initiative suggests dozens of investments are for non-food crops, including cotton, biofuels and rubber, or for projects explicitly targeting export markets.

Companies were invited to the table through the G8 New Alliance for Food Security and Nutrition initiative that pledges to accelerate agricultural production and lift 50 million people out of poverty by 2022.

But small farmers, who are supposed to be the main beneficiaries of the programme, have been shut out of the negotiations.

Olivier de Schutter, the UN special rapporteur on the right to food, said governments had been making promises to investors “completely behind the screen”, with “no long-term view about the future of smallholder farmers” and without their participation.

He described Africa as the last frontier for large-scale commercialfarming. “There’s a struggle for land, for investment, for seed systems, and first and foremost there’s a struggle for political influence,” he said.

Zitto Kabwe, the chairman of the Tanzanian parliament’s public accountscommittee, said he was “completely against” the commitments his government has made to bolster private investment in seeds.

“By introducing this market, farmers will have to depend on imported seeds. This will definitely affect small farmers. It will also kill innovation at the local level. We have seen this with manufacturing,” he said.

“It will be like colonialism. Farmers will not be able to farm until they import, linking farmers to [the] vulnerability of international prices. Big companies will benefit. We should not allow that.”

Tanzania’s tax commitments would also benefit companies rather than small farmers, he said, adding that the changes proposed would have to go through parliament. “The executive cannot just commit to these changes. These are sensitive issues. There has to be enough debate,” he said.

Million Belay, the head of the Alliance for Food Sovereignty in Africa (AFSA), said the initiative could spell disaster for small farmers in Africa. “It clearly puts seed production and distribution in the hands of companies,” he said.

“The trend is for companies to say they cannot invest in Africa without new laws … Yes, agriculture needs investment, but that shouldn’t be used as an excuse to bring greater control over farmers’ lives.

“More than any other time in history, the African food production system is being challenged. More than any other time in history outside forces are deciding the future of our farming systems.”

AFSA has also denounced the G8 initiative as ushering in a new wave of colonialism on the continent.

http://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2014/feb/18/g8-new-alliance-condemned-new-colonialism

As The 1960s Euphorea, The Current Africa Rising Optimism Is Illusionary Than Real: Let Us Actually Think How Africa Can Become Truly Prosperous. February 13, 2014

Posted by OromianEconomist in Africa, Africa Rising, African Poor, Aid to Africa, Corruption, Culture, Development, Dictatorship, Economics, Food Production, Human Rights, Ideas, Land Grabs in Africa, Ogaden, Omo, Oromia, Oromiyaa, Oromo, Oromo Nation, Self determination, Slavery, South Sudan, The Tyranny of Ethiopia, Tyranny, Uncategorized, Youth Unemployment.Tags: Africa, Africa Rising, African Studies, Developing country, Development, Development and Change, Economic and Social Freedom, Economic development, Economic growth, economics, Gadaa System, Genocide against the Oromo, Governance issues, Horn of Africa, Human rights, Human Rights and Liberties, Human rights violations, Land grabbing, Land grabs in Africa, National Self Determination, Oromia, Oromo, Oromo culture, Oromo people, Oromummaa, poverty, Social Sciences, State and Development, Sub-Saharan Africa, Tyranny, United Nations, Universal Declaration of Human Rights, World Bank

add a comment

‘Much of the “Africa Rising” narrative is based on the cyclical growth in income revenues from commodities. But who knows how long this will last? Dr Moghalu wants African governments to grasp hold of their future by creating industrial manufacturing so that Africans can consume what they produce. If that could be achieved, the continent will have moved away from being an import-driven consumer-driven economy. It is only then, he argues, that we can say Africa has truly risen.’

The term “Africa Rising” is on the lips of many these days particularly as seven of the world’s fastest growing economies are believed to be African. But can this current wave of Afro-optimism bring genuine prosperity to the African continent? Dr Kingsley Chiedu Moghalu, the Deputy Governor of the Central Bank of Nigeria thinks not.

“Hope is good,” he says. “But hope must be based on concrete substantive strategy going forward, so I pour a little bit of cold water of the Africa Rising phenomenon. I think it could lead to illusionary thinking. I recall that when African countries became independent that there was a huge sense of euphoria around the continent that independence guaranteed economic growth, political development and stability. But this did not happen in the following 30 to 40 years.”

In his latest book, Emerging Africa: How the Global Economy’s ‘Last Frontier’ can prosper and matter, Dr Moghalu presents his own ideas on how Africa can become truly prosperous. He describes it as “a vision for Africa’s future based on a fundamental analysis of why Africa has fallen behind in the world economy”.

In doing so, the LSE alumnus discusses some fundamental misunderstandings about which African states need to revise their assumptions.

The first is the idea that globalisation is automatically good. Rather, Dr Moghalu describes it as a huge and influential reality which Africans must engage with a sense of sophistication and self-interest. It is important to find a way to break that stranglehold because globalisation is neither benign in its intention nor agnostic in its belief. It is driven by an agenda and there are people who drive it.

Economist Dambisa Moyo caused controversy with her first book, Dead Aid: Why foreign aid isn’t working and how there is another way for Africa. Dr Moghalu echoes some of her arguments describing foreign aid as one of the leading reasons why Africa is impoverished. “It has removed the incentive of many African nations to seek solutions for their economic challenges and create wealth for their citizens,” he argues. “Instead it has perpetuated poverty because they are simply content to survive from one day to the next.”