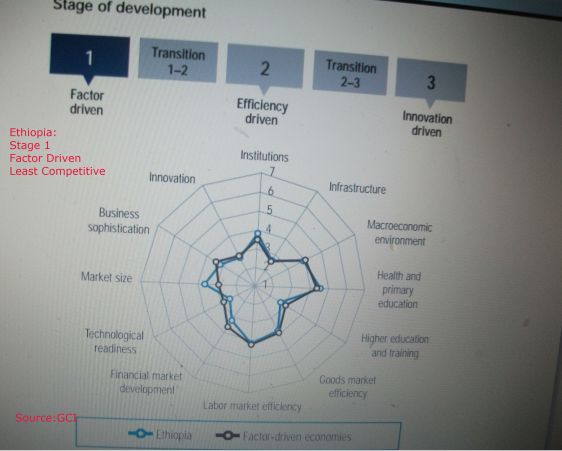

Posted by OromianEconomist in Currency Devaluation, Economics, Ethiopia the least competitive in the Global Competitiveness Index, Free development vs authoritarian model, Uncategorized.

Tags: Devaluation, economics, economy, Ethiopia's Birr, Inflation, Inflationary Devaluation

Economic Analysis: The cost of devaluing the Ethiopia’s Birr may outweigh its benefit

By Dr Mohammed Abbajebel Tahiro

The link between currency devaluation and domestic inflation

Ethiopia has been devaluing the Birr, in part because of pressures from the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Cheaper domestic currency, Vis a Vis major international currencies, makes exports more attractive to foreigners if a decent segment of the economy is based on manufacturing or, if the manufacturing sector is expanding and looking for international markets. Devaluing domestic currency makes exports more attractive to foreigners, which in turn spurs economic growth. The flip side of that is, cheaper domestic currency makes imports more expensive. Ethiopia imports medicine, fuel, food, and almost all productive capital, vehicles, and many more consumer goods. Cheaper currency means it takes more Birr to buy one foreign currency. Ethiopian importers will naturally raise their prices (inflation) to cover additional costs incurred because of a weaker Birr. The cost of devaluing the Ethiopian Birr may outweigh its benefit as the Ethiopian economy is still largely agricultural. The demand for agricultural products and minerals on the world market is largely stable and Ethiopia does not need to cheapen its currency to sell more to foreigners. The reason Africa can’t get a foothold in manufacturing is Chinese dumping of cheaply manufactured goods, not inability to access world markets for Africa’s manufactured goods. African infant manufacturing industry simply can’t compete with predatory practices of foreign manufacturers.

Ethiopia could simply let the exchange rate float. A floating exchange rate means the price of the Birr vis a vis major international currencies is determined by the relative supply and demand of the currencies. Consider the U.S. Dollar and the Birr are just goods like any other; say salt, just as in a free market the price of salt is determined by the supply and demand of salt, the exchange rate (price of Birr in Dollar) will be determined by the relative supply and demand of the two currencies. The United States follows floating exchange rate. In Ethiopia, the exchange rate is fixed by the National Bank. Fixed exchange rate always creates arbitrage opportunities as it seldom reflects the will of the international currency markets. The latest devaluation of the Birr ( 1USD = 27.07 Birr) will undoubtedly create more domestic price inflation as Ethiopian importers will raise prices on their imported goods. With the increase in the wage rate trailing far behind increase in prices, workers are getting a wage cut in real terms. Rising general level of prices means rising input prices. When input prices rise, manufacturers cut back on output, which means even more unemployment.

Inflation, two fundamental factors

When the Ethiopian parliament opened on Monday, President Mulatu Teshome made bold claims about the state of the Ethiopian economy. I will address the merits/demerits of that claim at a later date. Today, I will talk a little bit about the fundamental causes of domestic currency devaluation (inflation). There are two fundamental causes of currency depreciation:

1. The productive capacity of an economy.

2. The size of the money supply.

When an employee creates more value through increased productivity, his/her salary should increase proportionately. If the money supply in a country is fixed while productivity is increasing, each unit of currency will store greater value. On the other hand, if the increase in the money supply is proportionate to the increase in productivity, the amount of purchasing power (value) stored in each unit of currency remains unchanged. But, if you have a runaway money supply, that is, if the money supply grows faster than the growth in productivity, the value stored in each unit of currency decreases, and we call that inflation. When there’s more money in the economy than the productive capacity of the economy, the general level of prices increases and we call that demand-pull inflation. When prices of productive inputs rise, producers increase prices on finished products in order to recoup higher payments for input and, that can also lead to inflation; inflation created through an increase in input prices is called cost-push inflation. This source of inflation is less likely in Ethiopia as the manufacturing sector contributes less than 40% of the Ethiopian GDP.

The American Federal Reserve Bank’s counterpart in Ethiopia is the National Bank of Ethiopia. The National Bank is supposed to oversee the monetary policy of the country, including managing the money supply. The National Bank is supposed to be independent of undue political influence from the executive branch of the government. In Ethiopia today, appointments to key positions in the National Bank are based more on loyalty to the regime than professional aptitude. With that in mind, it’s easy to see how monetary policy could be mismanaged.

Ethiopia’s Attempt to Ease Dollar Shortage with Devaluation

By Barii Ayano

This is just to offer basic explanation of the issue without technical jargons. Exchange rate is the price of one country’s currency in terms of another country’s currency. For instance, the price of Birr in terms of U.S. dollar or vice versa. Exchange rates affect large flows of international trade (imports and exports). Foreign exchange facilitates flows of international investment, including foreign direct investments (FDI. Countries follow various exchange rate regimes: fixed exchange rate, pegged exchange rate, floating exchange rate, and managed floating exchange rate. The exchange rate regime of Ethiopia is characterized as managed floating exchange rate regime, which partly depends on supply and demand but with some government intervention in the exchange rate market, to concurrently adjust both exchange rates and foreign exchange reserves, monitored by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund.

What is Devaluation?

Devaluation is mainly government intervention in the exchange rate market of the country to determine the price of Birr in terms of dollar-some kind of government price setting. Simplified, devaluation makes Birr cheaper relative to the dollar, and hence you will need more Birr to get a dollar, compared to the current rate of exchange. In short, you need more Birr to buy a unit of dollar, and the people who can afford to buy dollar declines.

The recent announcement states that Ethiopia devalued its currency (Birr) by 15% per cent, which means you will need 15% more Birr to buy a dollar since Birr has become cheaper by 15%.

Why Do Countries Devalue their Currencies?

There are several reasons behind the need to devalue currencies. Some do it to promote exports and restrain imports. The simplified assumption is this. If the local currency becomes cheaper due to devaluation, foreigners can buy the local export products more cheaply and hence exports will increase. On the other hand, cheaper local currency can serve as an import restraint since foreign products become more expensive in local currency and importers need more Birr to buy foreign products, and hence increase the cost of living.

When it comes to the developing economies like Ethiopia, with limited export promotion power, the devaluation policy measure is mainly related to exchange rate stability due to imbalance between supply and demand of hard currencies. As repeatedly explained by the government officials, including the PM & the President, there is severe shortage of hard currencies in Ethiopia caused by limited hard currency earning power of Ethiopia’s exports whereas imports have grown folds more than exports. Ethiopia gets dollar from exports and needs dollar for the imports. The gap between the dollar earning and dollar spending capacity leads to part of the current account deficit called trade deficit (export values greater than import values). The gap has been expanding every year-even more so in recent years.

If you buy something (imports) you have to pay for it via exports, foreign aid in hard currency, remittances, etc. The growing gap between exports and imports is not sustainable. It’s important to note that foreign exchange rate crisis is one of the major sources of economic crises that ravaged the economies of a number of countries. Google exchange rate crisis to read more about it.

Therefore, the devaluation of Birr, which has been urged by the World Bank for years, is the policy measure undertaken by the regime to relieve a crippling dollar shortage and meager foreign exchange reserve of Ethiopia. The World Bank, EU, IMF, etc. cover the foreign exchange gap of Ethiopia so that the economy does not collapse due to the shortage of foreign exchange. Without international support and the Diasporas remittance, Ethiopia can easily become hard currency illiquid country that cannot pay for its imports or pay for its debts in hard currency.

Although the shortage of hard currency is a common phenomenon of poor countries with limited exports, the widening gap between Ethiopia’s earning and spending in hard currency is evidently not sustainable. It can kill economic growth. At worst, it can lead to economic crisis due to currency (exchange rate) crisis since there is vivid evidence of liquidity gap in hard currency in Ethiopia owing to its weak foreign exchange earning capacity. Illicit outflow of hard currency is another key problem aggravating the pain.

Simply put, devaluation is not a success story as some want us to believe. It’s a desperate policy measure undertaken to ease the pain of severe shortage of hard currency and its adverse impacts.

I will highlight the effects of devaluation on consumers, business, foreign exchange shortage, etc. in my next note.

A brief analysis of Birr devaluation

Posted by OromianEconomist in Economics, Ethiopia the least competitive in the Global Competitiveness Index, Uncategorized.

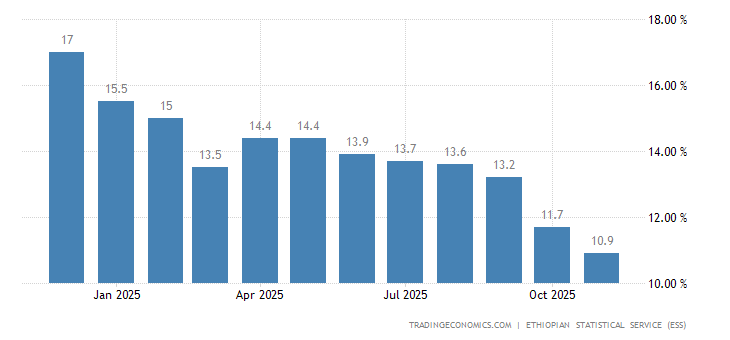

Tags: Africa, Economics and Finance, Inflation, Inflation and the Ethiopia rising meme, Inflation in Ethiopia, Trading Economics

Consumer prices in Ethiopia increased 10.4 percent year-on-year in August of 2017, following a 9.4 percent increase in July. It is the highest inflation rate since October of 2015 as food prices went up 13.3 percent, above 12.5 percent in July and non-food inflation rose to 7.1 percent from 5.9 percent in July. Inflation Rate in Ethiopia averaged 16.37 percent from 2006 until 2017, reaching an all time high of 64.20 percent in July of 2008 and a record low of -4.10 percent in September of 2009.

| Calendar |

GMT |

|

Actual |

Previous |

Consensus |

TEForecast |

| 2017-07-04 |

02:55 PM |

Inflation Rate YoY |

8.8% |

8.7% |

|

8.9% |

| 2017-08-03 |

02:30 PM |

Inflation Rate YoY |

9.4% |

8.8% |

|

9% |

| 2017-09-04 |

02:00 PM |

Inflation Rate YoY |

10.4% |

9.4% |

|

8.6% |

| 2017-10-10 |

11:00 AM |

Inflation Rate YoY |

|

10.4% |

|

7.7% |

| 2017-11-03 |

11:00 AM |

Inflation Rate YoY |

|

|

|

7.8% |

| 2017-12-05 |

11:00 AM |

Inflation Rate YoY |

|

|

|

7.9% |

|

In Ethiopia, the inflation rate measures a broad rise or fall in prices that consumers pay for a standard basket of goods. This page provides the latest reported value for – Ethiopia Inflation Rate – plus previous releases, historical high and low, short-term forecast and long-term prediction, economic calendar, survey consensus and news. Ethiopia Inflation Rate – actual data, historical chart and calendar of releases – was last updated on September of 2017.

|

Actual |

Previous |

Highest |

Lowest |

Dates |

Unit |

Frequency |

|

|

10.40 |

9.40 |

64.20 |

-4.10 |

2006 – 2017 |

percent |

Monthly |

|

Inflation Rate by Country

|

Last |

Previous |

Highest |

Lowest |

|

|

|

| Australia |

1.90 |

Jun/17 |

2.1 |

23.9 |

-1.3 |

% |

Quarterly |

|

| Brazil |

2.71 |

Jul/17 |

3 |

6821 |

1.65 |

% |

Monthly |

|

| Canada |

1.20 |

Jul/17 |

1 |

21.6 |

-17.8 |

% |

Monthly |

|

| China |

1.40 |

Jul/17 |

1.5 |

28.4 |

-2.2 |

% |

Monthly |

|

| Euro Area |

1.50 |

Aug/17 |

1.3 |

5 |

-0.7 |

% |

Monthly |

|

| France |

0.90 |

Aug/17 |

0.7 |

18.8 |

-0.7 |

% |

Monthly |

|

| Germany |

1.80 |

Aug/17 |

1.7 |

11.54 |

-7.62 |

% |

Monthly |

|

| India |

2.36 |

Jul/17 |

1.54 |

12.17 |

1.54 |

% |

Monthly |

|

| Indonesia |

3.82 |

Aug/17 |

3.88 |

82.4 |

-1.17 |

% |

Monthly |

|

| Italy |

1.20 |

Aug/17 |

1.1 |

25.64 |

-0.6 |

% |

Monthly |

|

| Japan |

0.40 |

Jul/17 |

0.4 |

24.9 |

-2.5 |

% |

Monthly |

|

| Mexico |

6.44 |

Jul/17 |

6.31 |

180 |

2.13 |

% |

Monthly |

|

| Netherlands |

1.30 |

Jul/17 |

1.1 |

11.19 |

-1.3 |

% |

Monthly |

|

| Russia |

3.90 |

Jul/17 |

4.4 |

2333 |

3.6 |

% |

Monthly |

|

| South Korea |

2.60 |

Aug/17 |

2.2 |

32.5 |

0.2 |

% |

Monthly |

|

| Spain |

1.60 |

Aug/17 |

1.5 |

28.43 |

-1.37 |

% |

Monthly |

|

| Switzerland |

0.30 |

Jul/17 |

0.2 |

11.92 |

-1.4 |

% |

Monthly |

|

| Turkey |

9.79 |

Jul/17 |

10.9 |

139 |

-4.01 |

% |

Monthly |

|

| United Kingdom |

2.60 |

Jul/17 |

2.6 |

8.5 |

-0.1 |

% |

Monthly |

|

| United States |

1.70 |

Jul/17 |

1.6 |

23.7 |

-15.8 |

% |

Monthly |

|

Posted by OromianEconomist in Africa, Africa Rising, African Poor, Economics: Development Theory and Policy applications, Ethiopia the least competitive in the Global Competitiveness Index, Ethiopia's Colonizing Structure and the Development Problems of People of Oromia, Afar, Ogaden, Sidama, Southern Ethiopia and the Omo Valley, Free development vs authoritarian model, Growth and Inequqlity, Poverty, The extents and dimensions of poverty in Ethiopia, Uncategorized.

Tags: Africa, Ethiopia, Ethiopia and poverty, Human Development Index for Oromia and Ethiopia, Multidimensional Poverty Index: Ethiopia has the second highest percentage of people who are MPI poor in the world: op Ten Poorest Countries in The World (All in #Africa) – MPI 2015 Ranking, poverty, Poverty and Famines: An Essay on Entitlement and Deprivation, UNDP

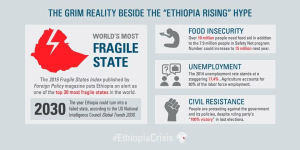

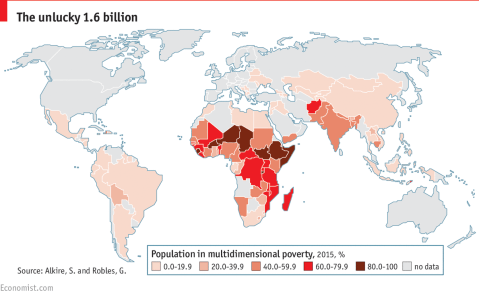

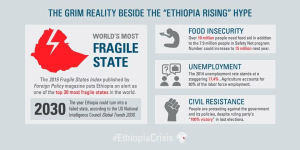

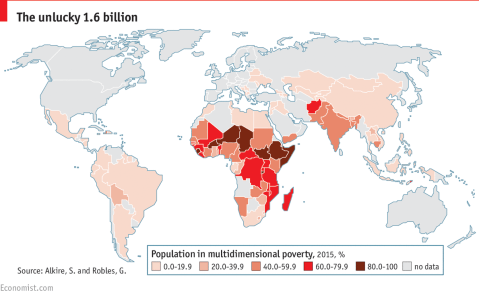

Multidimensional Poverty Index: Ethiopia has the second highest percentage of people who are MPI poor in the world: of Ten Poorest Countries in The World (All in #Africa) – MPI 2015 Ranking

‘Human development is a process of enlarging people’s choices—as they acquire more capabilities and enjoy more opportunities to use those capabilities. But human development is also the objective, so it is both a process and an outcome. Human development implies that people must influence the process that shapes their lives. In all this, economic growth is an important means to human development, but not the goal. Human development is development of the people through building human capabilities, for the people by improving their lives and by the people through active participation in the processes that shape their lives. It is broader than other approaches, such as the human resource approach, the basic needs approach and the human welfare approach.’ -UNDP 2015 Report

Ethiopia’s HDI value for 2014 is 0.442— which put the country in the low human development category— positioning it at 174 out of 188 countries and territories.

In Ethiopia 88.2 percent of the population (78,887 thousand people) are multidimensionally poor while an additional 6.7 percent live near multidimensional poverty (6,016 thousand people). The breadth of deprivation (intensity) in Ethiopia, which is the average of deprivation scores experienced by people in multidimensional poverty, is 60.9 percent. The MPI, which is the share of the population that is multidimensionally poor, adjusted by the intensity of the deprivations, is 0.537. Rwanda and Uganda have MPIs of 0.352 and 0.359 respectively. Ethiopia, UNDP country notes

(Sunday Adelaja’s Blog) — When Poverty and non-existent double digit growth met face-to-Face at a dumpster site called KORA in Ethiopia. As we speak, thousands of people in Addis Ababa survive from the leftover “food” dumped in such dumpsters. People, in fact, used to call them “Dumpster Dieters”. They are either the byproducts or victims of the cooked economic figures. You be the judge!

Yet the new measurement known as the Multidimensional Poverty Index, or MPI, that will replace the Human Poverty index in the United Nations’ annual Human Development Report says that Ethiopia has the second highest percentage of people who are MPI poor in the world, with only the west African nation of Niger fairing worse. You probably heard that Ethiopia has been a fast growing economy in the content recording very high growth rate not just in Africa but the world as well.

This comes as more international analysts have also began to question the accuracy of the Meles government’s double digit economic growth claims and similar disputed government statistics referred by institutions like the IMF. The list starts with the poorest.

- Niger

- Ethiopia

- Mali

- Burkina Faso

- Burundi

- Somalia

- Central African Republic

- Liberia

- Guinea

- Sierra Leone

What is the MPI?

People living in poverty are affected by more than just income. The Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) complements a traditional focus on income to reflect the deprivations that a poor person faces all at once with respect to education, health and living standard. It assesses poverty at the individual level, with poor persons being those who are multiply deprived, and the extent of their poverty being measured by therange of their deprivations.

Why is the MPI useful?

According to the UNDP report, the MPI is a high resolution lens on poverty – it shows the nature of poverty better than income alone. Knowing not just who is poor but how they are poor is essential for effective humandevelopment programs and policies. This straightforward yet rigorous index allows governments and other policymakers to understand the various sources of poverty for a region, population group, or nation and target their humandevelopment plans accordingly. The index can also be used to show shifts in the composition of poverty over time so that progress, or the lack of it, can be monitored.

The MPI goes beyond previous international measures of poverty to:

-

Show all the deprivations that impact someone’s life at the same time – so it can inform a holistic response.

-

Identify the poorest people. Such information is vital to target people living in poverty so they benefit from key interventions.

-

Show which deprivations are most common in different regions and among different groups, so that resources can be allocated and policies designed to address their particular needs.

-

Reflect the results of effective policy interventions quickly. Because the MPI measures outcomes directly, it will immediately reflect changes such as school enrolment, whereas it can take time for this to affect income.

Posted by OromianEconomist in Ethiopia the least competitive in the Global Competitiveness Index, Poverty.

Tags: Africa, Ethiopia & The Global Innovation Index, Ethiopia and poverty, Ethiopia and social progress index, Ethiopia's higher-education boom built on shoddy foundations

OMN

(OMN: Oduu Adol.12,2015): Guddinni dinaagdee Itoophiyaa waggoota sadan dhufan keessatti,harka lamaan akka gadi bu’uu Baankiin Addunyaa gabaase. Baankiin Addinyaa gadi bu’uu guddinna dinaagdee Itoophiyaa kan hime, gabaasaa bara 2015 guddina diinagdee Itoophiyaa ilaalchisuun baaseen akka ta’e barameera.

Gabaasni waggaa kanaa baankiin addunyaa guddina diinagdee Itoophiyaa ilaalchisuun baase akka mul’isutti, guddinni diinagdee Itoophiyaa,waggoota itti’aanan kanatti ni dabala jedhamee eegamaa ture qabxii lamaan akka gadi bu’u baankiin Addunyaa himeera.

Gabaasni Baankiin Addunyaa kun, sababaa gadi bu’iinsaa diinaagdee Itoophiyaa yoo himu, sochiileen investimeetiifi konistraakshiinii qabbana’uun isaanii qancaruu diinaangdeef kanneen duraati jechuun Baankii Addunyaatti, itti gaafatamaan sagantaa diinaagdee Laarsi Moolar dabbataneeran.

Gaabasni baankii Addunyaa kun itti dabaluun akka beeksisetti, sochiin daldala biyya alaa qabbana’a dhufuusaatiin humni maallaqa sharafa biyya alaafi baajanni fiisikaala mootummaalle rakkoo keessa seenuun, sochii daldala biyya alaatiifi biyya keessaa giddutti madaalliin duufuun sharafni biyya alaa dhabamuun diinaagdee Itoophiyaa rakkoo keessa akka galchu addeeffameera.

Liqaan biyyootaa alaa Itoophiyaa irra jirulle, dhibeentaa 45 irraa gara 65 tti akka ol guddatu gaabsni baankii addunyaa kun saaxileera. Liqaa biyyoonni alaa Itoophiyaa irraa qaban kana kan akka malee ol kaasaa jiru, liqaa baroota dheeraafi dhala gadi bu’aa waliin kanfalamurra, liqaan yeroo gabaabaa keessatti kafalamuufi dhala hedduu dhalu heddummaachaa waan dhufeef akka ta’ee gabaasni Baankii Addunyaa kun addeesseera. Gabaa Addunyaa irratti dabalaa dhufuun humnni jijjiirraa doolaralle, liqaa ittoophiyaa irra jiru ol kaasaa jira jedhameera. Gatiin doolaara yeroo gabaabaa keessatti dhibeentaa 25n dabalaa akka dhufe ragaaleen agarsiisanii jiran.

Gabaasaan Daani’eel Bariisoo Areerii.

Posted by OromianEconomist in Ethiopia the least competitive in the Global Competitiveness Index, Free development vs authoritarian model, Schools in Oromia, The Global Innovation Index, Uncategorized.

Tags: Africa, African Studies, Education and Development, Ethiopia & The Global Innovation Index, Ethiopia's higher-education boom built on shoddy foundations, Oromo University Students And Their National Demand, Weak institution

The country desperately needs new universities to drive development, but most of the 30 built in the last 15 years fall woefully short

The declining standard of Nigeria’s premier institution, the University of Ibadan, ten years ago is reflected in Ethiopia where the quality of new universities varies widely. Photograph: George Esiri/REUTERS

Ethiopia’s higher education infrastructure has mushroomed in the last 15 years. But the institutions suffer from half-written curriculums, unqualified – but party-loyal – lecturers, and shoddily built institutions. The rapid growth of Ethiopia’s higher education system has come at a cost, but it is moving forward all the same.

Twenty years ago the Ethiopian government launched a huge and ambitious development strategy that called for “the cultivation of citizens with an all-round education capable of playing a conscious and active role in the economic, social, and political life of the country”. One of the principal results of Ethiopia’sagricultural development-led industrialisation strategy (ADLI) has been a rapid expansion in the country’s higher education system. In 2000 there were just two universities, but since then the country has built 29 more, with plans for another 11 to be completed within two years.

The quality of these new universities varies widely; from thriving research schools, to substandard institutions built to bolster the regime’s power in hostile regions. One professor recalls a hurried evacuation from part of a recently completed university while he was working there: one of the buildings had collapsed.

But there have also been success stories. The University of Jimma, for example, has come first in the Ethiopian Ministry of Education’s rankings for the past five years, and is held up as evidence of ADLI’s efficacy since its establishment in 1999. The most recent development at Jimma, the department of materials science and engineering (MSE), opened for students in 2013, and has quickly expanded to become one of the top research schools in the sub-Saharan region. The department’s founder, Dr Ali Eftekhari, has since received a fellowship from the African Academy of Sciences on the back of the project’s success.

This success is much-needed. At 8%, African higher education enrolment issignificantly lower than the global average of 32%, and Ethiopia trails even further behind, with fewer than 6% of college-age adults at university. Research in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (Stem) is starting from a particularly low base in Africa. The World Bank reported last year that though the sub-Saharan region has “increased both the quantity and quality of its research” in recent years, much of this improvement is due to international collaboration, and a lack of native Africans is “reducing the economic impact and relevance of research”.

Dr Eftekhari echoes these concerns: “The problem for development in Ethiopiaand similar African countries is higher education itself. This is the reason that I focused on PhD programs. “For instance, Jimma’s department of civil engineering has over 3,000 undergraduate students. These civil engineers are the future builders of the country, but there is not one PhD holder among the staff; most only have a BSc.”

Eftekhari improvised and sweet-talked in order to get the department established; in its first year, the department taught 18 PhD students – all native Ethiopians – on almost zero budget, with staff donating their time and money until funding was secured from the ministry of education. Despite the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front’s (EPRDF) push for development, Ethiopia’s political landscape remains a minefield for education professionals, says Eftekhari: “People are always suspicious about the political reasons behind each new project. I decided to start with zero budget to allay those doubts. In developing countries everything has some degree of flexibility. I used this to borrow staff and resources from the rest of the university until we could secure a budget.

“Many of the staff saw the project as a career opportunity,” says Eftekhari, but altruism also played a part. The department’s research focuses primarily on solving the country’s pressing poverty and development problems. “They knew they were actually saving lives,” says Jimma’s innovation coordinator, Maria Shou.

The belief that science and engineering is key to alleviating poverty propels the work of the school. Projects range from the development of super-capacitors for the provision of cheap power, to carbon nanomaterials for Ethiopia’s expanding construction industry. “You only need a couple of weeks in Ethiopia to realise that materials science is a priority,” says Pablo Corrochano, an assistant professor at the school. “Even in the capital you’ll experience cuts in power and water; in rural areas it’s even worse. Producing quality and inexpensive bricks for building houses, designing active water filters, and supplying ‘off-the-grid’ energy systems for rural areas are all vital to the country’s development.”

However, Jimma’s success could be seen as a bit of an anomaly. Paul O’Keeffe, a researcher at La Sapienza University of Rome, who specialises in Ethiopia’s higher education system, believes that similar initiatives are needed, but that the government’s politics are an obstacle: “My research indicates that the rapid expansion of the public university system has seen a dramatic decline in the quality of education offered in recent years. Instead of putting resources into improving the existing system, or establishing a few good institutions, the EPRDF has built many new universities, largely for political reasons.

“A lot of the time the universities are merely shells. They do not function as universities as we would expect and are poorly resourced, and in some cases shoddily built. It would seem that they are built almost as a token where the EPRDF can say to hostile regions ‘look we are doing something for you, we’ve built a university’.”

Even when the universities do function, the quality of education is often low: “Once the funding, say from a western development agency, is finished for a particular course, it is no longer taught as the university authorities believe they can get funding for a new course instead; whatever is the latest fashionable course. So often this type of education for development is not sustainable.”

Reports of spies, classroom propaganda, of curriculums that have been abandoned half-written due to funding cuts, and of unqualified staff are common at these universities, which make up the bulk of Ethiopian higher education, says O’Keeffe. “The party line is peddled during class, students are required to join the party, [there are] various reports of spies in the classrooms, who monitor what is said and who says it.”

A lecturer at Addis Ababa University, who wished to remain anonymous, is concerned primarily with the lack of qualifications among staff: “What is disturbing is that those who have just graduated with BAs and MAs are the lecturers. That is the manpower that they have. If you talk with students you wouldn’t believe that these students actually graduated from these so-called universities. Their inability to articulate their thoughts is breathtaking. It is extremely frustrating and you wonder how they have spent four years at university studying a doctorate.”

In this context, the MSE school provides a beacon of hope. The school’s success demonstrates that higher education – Stem research in particular – has the potential to thrive and play a central role in helping Ethiopia to reach its goal of becoming a middle-income nation by 2025, provided political interests are put to one side. Let’s hope the EPRDF takes note.

http://www.theguardian.com/global-development-professionals-network/2015/jun/22/ethiopia-higher-eduction-universities-development

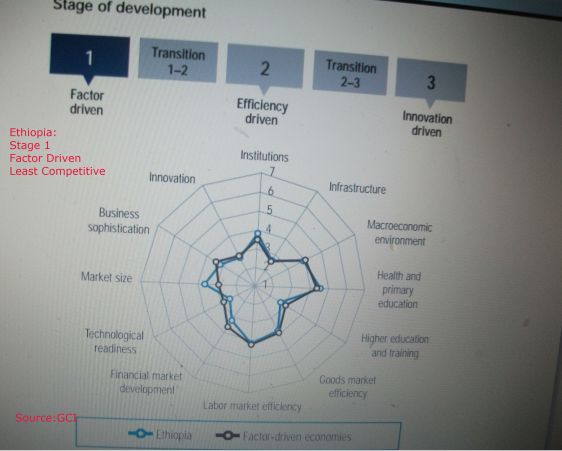

Posted by OromianEconomist in Africa, Developed country, Development & Change, Economics, Ethiopia the least competitive in the Global Competitiveness Index.

Tags: Africa, African Studies, Economic development, economics, Human Capital Index 2015, Human development Index, Human Development Index for Oromia and Ethiopia, World Economic Forum

Ethiopia Ranks 115 out of 124 countries in Human Capital Index 2015 Rank

Ethiopia ranks at 115 out of 124 countries in the ‘Human Capital Index’ because of its poor performance on educational outcomes, says the Human Capital Report 2015 issued by the World Economic Forum (WEF).

The index is dominated by European countries with two countries from the Asia and Pacific region and one from the North America region also making it into the top 10.

Finland topped the ranking of the Human Capital Index in 2015, scoring 86% of its human capital, followed by Norway, Switzerland, Canada and Japan.

Sweden, Denmark, the Netherlands, New Zealand and Belgium also seized the places in the top 10 list. Ethiopia scored 50.25 out of 100.

The leaders of the index are high-income economies that have placed importance on high educational attainment and a correspondingly large share of high-skilled employment.

The World Economic Forum (WEF) released the Human Capital Report 2015 in Geneva, Switzerland on Thursday 14 May 2015.

The WEF prepared the report in collaboration with Mercer, an American global human resource and related financial services consulting firm.

The report elaborates the status of different countries across the world on the Human Capital Index and provides key inputs for policy makers to augment capacities of human capital in 124 countries it has surveyed.

In the index, WEF highlighted Ethiopia’s scarcity of skilled employees, poor ability to nurture talent through educating, training and employing its people.

“Talent, not capital, will be the key factor linking innovation, competitiveness and growth in the 21st century,” said WEF Executive Chairman Klaus Schwab releasing the report at a news conference in Cologny, near Geneva, Switzerland.

In sub-Saharan Africa, Mauritius (72) holds the highest position in the region. While another six countries rank between 80 and 100, another 17 countries from Africa rank below 100 in the index. South Africa is in 92nd place and Kenya at 101. The region’s most populous country, Nigeria (120) is among the bottom three in the region, while the second most populous country, Ethiopia, is in 115th place. With the exception of the top-ranked country, the region is characterized by chronically low investment in education and learning.

Human Capital Index 2015 regional Ranks

Except Yemen (40.7) all the 10 poorest performers are African Countries: Ethiopia (50.25), Burkina Faso (49.22), Ivory Coast ( 49.02), Mali (48.51), Guinea (48.25), Nigeria (48.43), Burundi (46.76), Mauritania (42.29) and Chad (41.1).

The countries are ranked on the basis of 46 indicators that track “how well countries are developing and deploying their human capital focusing on education, skills and employment”.

The index takes a life-course approach to human capital, evaluating the levels of education, skills and employment available to people in five distinct age groups, starting from under 15 years to over 65 years. The aim is to assess the outcome of past and present investments in human capital and offer insight into what a country’s talent base will look like in the future.

http://reports.weforum.org/human-capital-report-2015/press-releases/

Posted by OromianEconomist in Africa, Africa Rising, Ethiopia the least competitive in the Global Competitiveness Index, Ethiopia's Colonizing Structure and the Development Problems of People of Oromia, The 2014 Ibrahim Index of African Governance, The extents and dimensions of poverty in Ethiopia, The State of Food Insecurity in Ethiopia, The Tyranny of TPLF Ethiopia.

Tags: Africa, African Studies, Economic and Social Freedom, economics, Ethiopia, Ethiopia and the social progress index, If Ethiopia’s economy is so vibrant, State and Development, Tyranny and poverty

If Ethiopia is so vibrant, why are young people leaving?

Al Jazeera

April 28, 2015

Within a week, Ethiopians were hit with a quadruple whammy. On April 19, the Libyan branch of the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) released a shocking video purporting to show the killings and beheadings of Ethiopian Christians attempting to cross to Europe through Libya. This came only days after an anti-immigrant mob in South Africa killed at least three Ethiopian immigrants and wounded many others. Al Jazeera America reported that thousands of Ethiopian nationals were stranded in war-torn Yemen. And in the town of Robe in Oromia and its surroundings alone, scores of people were reportedly grieving over the loss of family members at sea aboard a fateful Europe-bound boat that sank April 19 off the coast of Libya with close to 900 aboard.

These tragedies may have temporarily united Ethiopians of all faiths and ethnic backgrounds. But they have also raised questions about what kind of desperation drove these migrants to leave their country and risk journeys through sun-scorched deserts and via chancy boats.

The crisis comes at a time when Ethiopia’s economic transformation in the last decade is being hailed as nothing short of a miracle, with some comparing it to the feat achieved by the Asian “tigers” in the 1970s. Why would thousands of young men and women flee their country, whose economy is the fastest growing in Africa andwhose democracy is supposedly blossoming? And when will the exodus end?

After the spate of sad news, government spokesman Redwan Hussein said the tragedy “will be a warning to people who wish to risk and travel to Europe through the dangerous route.” Warned or not, many youths simply do not see their dreams for a better life realized in Ethiopia. Observers cite massive poverty, rising costs of living, fast-climbing youth unemployment, lack of economic opportunities for the less politically connected, the economy’s overreliance on the service sector and the requirement of party membership as a condition for employment as the drivers behind the exodus.

A 2012 study by the London-based International Growth Center noted (PDF) widespread urban unemployment amid growing youth landlessness and insignificant job creation in rural areas. “There have been significant increases in educational attainment. However, there has not been as much job creation to provide employment opportunities to the newly educated job seekers,” the report said.

One of the few ISIL victims identified thus far was expelled from Saudi Arabia in 2013. (Saudi deported more than 100,000 Ethiopian domestic workers during a visa crackdown.) A friend, who worked as a technician for the state-run Ethiopian Electricity Agency, joined him on this fateful trek to Libya. At least a handful of the victims who have been identified thus far were said to be college graduates.

Given the depth of poverty, Ethiopia’s much-celebrated economic growth is nowhere close to accommodating the country’s young and expanding population, one of the largest youth cohorts in Africa. Government remainsthe main employer in Ethiopia after agriculture and commerce. However, as Human Rights Watch noted in 2011, “access to seeds, fertilizers, tools and loans … public sector jobs, educational opportunities and even food assistance” is often contingent on support for the ruling party.

Still, unemployment and lack of economic opportunities are not the only reasons for the excessive outward migration. These conditions are compounded by the fact that youths, ever more censored and denied access to the Internet and alternative sources of information, simply do not trust the government enough to heed Hussein’s warnings. Furthermore, the vast majority of Ethiopian migrants are political refugees fleeing persecution. There are nearly 7,000 registered Ethiopian refugees in Yemen, Kenya has more than 20,000, and Egypt and Somalia have nearly 3,000 each, according to the United Nations refugee agency.

As long as Ethiopia focuses on security, the door is left wide open for further exodus and potential social unrest from an increasingly despondent populace.

Ethiopians will head to the polls in a few weeks. Typically, elections are occasions to make important choices and vent anger at the incumbent. But on May 24, Ethiopians will be able to do neither. In the last decade, authorities have systematically closed the political space through a series of anti-terrorism, press and civil society laws. Ethiopia’s ruling party, now in power for close to 24 years, won the last four elections. The government has systematically weakened the opposition and does not tolerate any form of dissent.

The heightened crackdown on freedom of expression has earned Ethiopia the distinction of being the world’sfourth-most-censored country and the second leading jailer of journalists in Africa, behind only its archrival, Eritrea, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists.

There is little hope that the 2015 elections would be fundamentally different from the 2010 polls, in which the ruling party won all but two of the 547 seats in the rubber-stamp national parliament. The ruling party maintains a monopoly over the media. Authorities have shown little interest in opening up the political space for a more robust electoral contest. This was exemplified by the exclusion of key opposition parties from the race, continuing repression of those running and Leenco Lata’s recent failed attempt to return home to pursue peaceful political struggle after two decades of exile. (Lata is the founder of the outlawed Oromo Liberation Front, fighting since 1973 for the rights of the Oromo, Ethiopia’s marginalized majority population, and the president of the Oromo Democratic Front.)

A few faces from the fragmented and embittered opposition maybe elected to parliament in next month’s lackluster elections. But far from healing Ethiopia’s gashing wounds, the vote is likely to ratchet up tensions. In fact, a sea of youth, many too young to vote, breaking police barriers to join opposition rallies bespeaks not of a country ready for elections but one ripe for a revolution with unpredictable consequences.

Despite these mounting challenges, Ethiopia’s relative stability — compared with its deeply troubled neighbors Somalia, South Sudan, Eritrea and Djibouti — is beyond contention. Even looking further afield, across the Red Sea, where Yemen is unraveling, one finds few examples of relative stability. This dynamic and Ethiopia’s role in the “war on terrorism” explains Washington’s and other donors’ failure to push Ethiopia toward political liberalization.

However, Ethiopia’s modicum of stability is illusory and bought at a hefty price: erosion of political freedoms, gross human rights violations and ever-growing discontent. This bodes ill for a country split by religious, ethnic and political cleavages. While at loggerheads with each other, Ethiopia’s two largest ethnic groups — the Oromo (40 percent) and the Amhara (30 percent) — are increasingly incensed by continuing domination by Tigreans (6 percent).

Ethiopian Muslims (a third of the country’s population of 94 million) have been staging protests throughout the country since 2011. Christian-Muslim relations, historically cordial, are being tested by religious-inspired violence and religious revivalism around the world. Ethiopia faces rising pressures to choose among three paths fraught with risks: the distasteful status quo; increased devolution of power, which risks balkanization; and more centralization, which promises even further resistance and turmoil.

It is unlikely that the soul searching from recent tragedies will prompt the authorities to make a course adjustment. If the country’s history of missed opportunities for all-inclusive political and economic transformation is any guide, Ethiopians might be in for a spate of more sad news. As long as the answer to these questions focuses on security, the door is left wide open for further exodus and potential social unrest from an increasingly despondent populace.

Posted by OromianEconomist in Africa, African Internet Censorship, Amnesty International's Report: Because I Am Oromo, Ethiopia & World Press Index 2014, Ethiopia the least competitive in the Global Competitiveness Index.

Tags: Africa, African Studies, Ethiopia & The Global Innovation Index, Ethiopia and Internet censorship, Ethiopia and the social progress index, The Tyranny of Ethiopia

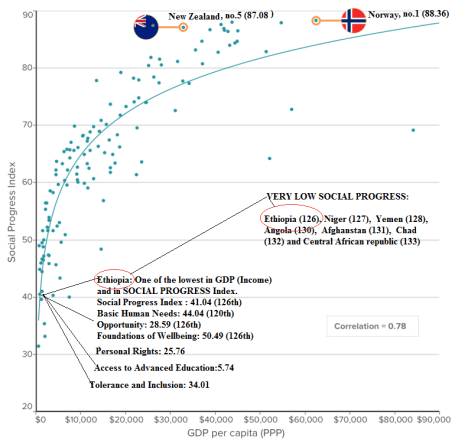

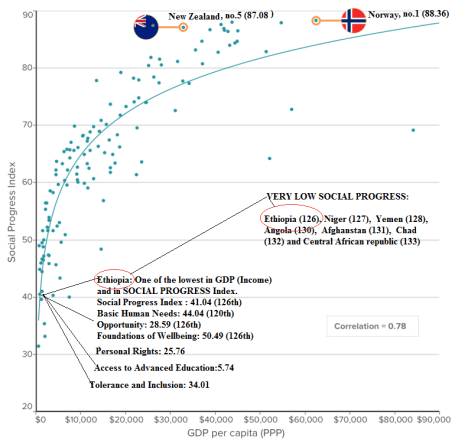

In measuring national progress, Ethiopia as in its GDP per head records one of the lowest in Social Progress Index 2015. Ethiopia ranks 126 of 133 countries.

‘The Social Progress Index offers a rich framework for measuring the multiple dimensions of social progress, benchmarking success, and catalyzing greater human wellbeing…. Economic growth alone is not enough. A society that fails to address basic human needs, equip citizens to improve their quality of life, protect the environment, and provide opportunity for many of its citizens is not succeeding. We must widen our understanding of the success of societies beyond economic outcomes. Inclusive growth requires achieving both economic and social progress.’

http://www.socialprogressimperative.org/data/spi#data_table/countries/spi/dim1,dim2,dim3

Click to access 2015%20SOCIAL%20PROGRESS%20INDEX_FINAL.pdf

COUNTRIES WITH VERY LOW SOCIAL PROGRESS ARE:

Ethiopia (126), Niger (127), Yemen (128), Angola (130), Afghanstan (131), Chad (132) and Central African republic (133).

Ethiopia’s outcome:

One of the lowest in GDP (Income) and in SOCIAL PROGRESS Index.

Social Progress Index : 41.04 (126th)

Basic Human Needs: 44.04 (120th)

Opportunity: 28.59 (126th)

Foundations of Wellbeing: 50.49 (126th)

Water and Sanitation: 23.50

(Access to piped water, Rural access to improved water source, Access to improved sanitation facilities).

Personal Rights: 25.76

(Political rights, Freedom of speech, Freedom of assembly/association, Freedom of movement, Private property rights).

Access to Information and Communications:33.09

(Mobile telephone subscriptions, Internet users, Press Freedom Index)

Tolerance and Inclusion: 34.01

(Discrimination and violence against minorities, Religious tolerance,Community safety net).

Access to Advanced Education:5.74

(Years of tertiary schooling, Women’s average years in school,Inequality in the attainment of education, Globally ranked universities).

- Ten countries in the world have been ranked as Very High Social Progress Countries as these countries generally have strong performance across all three dimensions. The average dimension scores for this tier are: Basic Human Needs is 94.77, Foundations of Wellbeing is 83.85, and Opportunity is 83.07.

- As with most high-income countries, the top 10 countries score lowest on Ecosystem Sustainability and Health and Wellness.

- Nearly all of the top 10 are relatively small countries, with only Canada having a population greater than 25 million.

- The top three countries in the world on Social Progress are Norway, Sweden, and Switzerland with closely grouped scores between 88.36 and 87.97.

- Canada is the only country among the G7 countries that has been ranked in top ten on SPI 2015

- Under the High Social Progress Countries tier, there are 21 countries. This group includes a number of the world’s leading economies in terms of GDP and population, including the remaining six members of the G7: the United Kingdom, Germany, Japan, the United States, France, and Italy. The average dimension scores for this tier are: Basic Human Needs is 90.86, Foundations of Wellbeing is 77.83, and Opportunity is 73.82

- The third tier of Upper Middle Social Progress Countries comprises of 25 countries. This group reveals that high GDP per capita does not guarantee social progress. Average scores for this tier are: Basic Human Needs is 80.66, Foundations of Wellbeing is 73.52, and Opportunity is 57.73.

- The fourth tier Lower Middle Social Progress Countries comprises of 42 countries. The average dimension scores for this tier are: Basic Human Needs is 72.34, Foundations of Wellbeing is 66.90, and Opportunity is 47.14

- Under the Low Social Progress Countries tier, there are 27 countries which include many Sub-Saharan African countries. The average dimension scores for this tier are: Basic Human Needs is 50.03, Foundations of Wellbeing is 58.01, and Opportunity is 38.35.

- Under the Very Low Social Progress Countries tier, there are 8 countries. The average dimension scores for this tier are: Basic Human Needs is 38.46, Foundations of Wellbeing is 48.55, and Opportunity is 26.05.

- The lowest five countries in the world on Social Progress are Ethiopia, Niger, Afghanistan, Chad, Central African Republic.

The Social Progress Index, first released in 2014 building on a beta version previewed in 2013, measures a comprehensive array of components of social and environmental performance and aggregates them into an overall framework. The Index was developed based on extensive discussions with stakeholders around the world about what has been missed when policymakers focus on GDP to the exclusion of social performance. Our work was influenced by the seminal contributions of Amartya Sen on social development, as well as by the recent call for action in the report “Mismeasuring Our Lives” by the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress.

The Social Progress Index incorporates four key design principles:

- Exclusively social and environmental indicators: our aim is to measure social progress directly, rather than utilize economic proxies. By excluding economic indicators, we can, for the first time, rigorously and systematically analyze the relationship between economic development (measured for example by GDP per capita) and social development. Prior efforts to move “beyond GDP” have comingled social and economic indicators, making it difficult to disentangle cause and effect.

- Outcomes not inputs: our aim is to measure the outcomes that matter to the lives of real people, not the inputs. For example, we want to measure a country’s health and wellness achieved, not how much effort is expended nor how much the country spends on healthcare.

- Holistic and relevant to all countries: our aim is to create a holistic measure of social progress that encompasses the many aspects of health of societies. Most previous efforts have focused on the poorest countries, for understandable reasons. But knowing what constitutes a healthy society for any country, including higher-income countries, is indispensable in charting a course for less-prosperous societies to get there.

- Actionable: the Index aims to be a practical tool that will help leaders and practitioners in government, business and civil society to implement policies and programs that will drive faster social progress. To achieve that goal, we measure outcomes in a granular way that focuses on specific areas that can be implemented directly. The Index is structured around 12 components and 52 distinct indicators. The framework allows us to not only provide an aggregate country score and ranking, but also to allow granular analyses of specific areas of strength and weakness. Transparency of measurement using a comprehensive framework allows change-makers to identify and act upon the most pressing issues in their societies.

These design principles are the foundation for our conceptual framework. We define social progress in a comprehensive and inclusive way. Social progress is the capacity of a society to meet the basic human needs of its citizens, establish the building blocks that allow citizens and communities to enhance and sustain the quality of their lives, and create the conditions for all individuals to reach their full potential.

This definition reflects an extensive and critical review and synthesis of both the academic and practitioner literature in a wide range of development topics. The Social Progress Index framework focuses on three distinct (though related) questions:

- Does a country provide for its people’s most essential needs?

- Are the building blocks in place for individuals and communities to enhance and sustain wellbeing?

- Is there opportunity for all individuals to reach their full potential?

These three questions define the three dimensions of Social Progress: Basic Human Needs, Foundations of Wellbeing, and Opportunity.

http://www.socialprogressimperative.org/data/spi/methodology

Posted by OromianEconomist in Africa Rising, African Poor, Corruption in Africa, Ethiopia the least competitive in the Global Competitiveness Index, Ethiopia's Colonizing Structure and the Development Problems of People of Oromia, Free development vs authoritarian model.

Tags: Africa, Africa Rising, The Tyranny of Ethiopia

While the majority of the population is getting poorer and poorer every year, a minority of the population, especially those loyal to the ruling party, are becoming millionaires overnight. The exaggerated economic development rhetoric of EPRDF is unsubstantiated for it is not based on facts and is against what is happening on the ground. It is simply a means to cover up the unspeakable atrocities they are inflicting up on the people. The inflation that we, ordinary people, are suffering from is mainly their own making. Because of inflation, an item which used to cost one Birr a year ago now costs one birr and 40 cents. This shows that the value of one Birr is approximately 72 cents. http://allafrica.com/stories/201504071221.html

While the majority of the population is getting poorer and poorer every year, a minority of the population, especially those loyal to the ruling party, are becoming millionaires overnight. The exaggerated economic development rhetoric of EPRDF is unsubstantiated for it is not based on facts and is against what is happening on the ground. It is simply a means to cover up the unspeakable atrocities they are inflicting up on the people. The inflation that we, ordinary people, are suffering from is mainly their own making. Because of inflation, an item which used to cost one Birr a year ago now costs one birr and 40 cents. This shows that the value of one Birr is approximately 72 cents. http://allafrica.com/stories/201504071221.html

Ethiopia: Why EPRDF’s Growth Rhetoric Is Faulty

Eidmon Tesfaye*

OPINION, allafrica.com

By and large, Ethiopia recorded 17 years of economic stagnation under the leadership of the Dergue, a military government. For example, in 1990/91, the growth rate of the Ethiopian gross domestic product (GDP) was negative 3.2pc, whereas cyclical unemployment was about 12pc, the rate of inflation was about 21pc, and the country’s budget was at a deficit of 29pc of GDP. For the last five years, Ethiopia has gathered momentum by recording steady economic growth. Along with this growth, however, the country has seen an accelerated, double-digit increase in the price of goods and services. The very common way that the EPRDF and its agents try to shift the public attention from lack of human and democratic rights and the daylight looting of the country’s resources, is by referring to the ‘impressive’ economic development registered in their rule. If they are talking about the only region that they are exclusively devoted to developing, then, they are absolutely right.

The reality in other regions of the country, however, speaks quite the opposite. Even if we believe the double digit economic growth that the EPRDF claims to have registered in the last five years, it all will be dwarfed by the sky high rate of inflation, the second highest in Africa – the first being Zimbabwe which is actually experiencing a currency collapse. Thus, inflation has remained a scourge of the Ethiopian economy. Stated in simple words, Ethiopia, at this juncture, is faced with an overheating economy. With the global soaring prices of oil, wheat, corn, and minerals, this condition cannot be regarded as unique to the Ethiopian situation. What makes the Ethiopian case a special one is that Ethiopia is a low-income country. The increase in the Consumer Price Index (the main gauge of inflation), has become very detrimental to the low-income groups and retirees who live with fixed incomes. The risk of inflationary pressure is reducing the purchasing power of the Ethiopian Birr. Because of inflation, an item which used to cost one Birr a year ago now costs one birr and 40 cents. This shows that the value of one Birr is approximately 72 cents. As it stands, financial liberalisation is not an option. Financial intermediaries may accelerate inflation if the National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE) relaxes its financial and monetary policies that regulate them to maintain the statutory liquidity requirement of demand and time deposits. In addition, an increase in money supply could accelerate inflation if the central bank substantially reduces the discount rate or buys existing government bonds from investors. The discount rate is the interest rate charged by the NBE when member banks borrow from it. Ethiopian banks overuse their reserve facilities to boost their credit portfolio. The excess reserve in Ethiopia was due to more savings. The demand for bank credit rose sharply to finance large scale investment projects by the public enterprises and the rapidly expanding private sector. Substantial negative real interest rates and commercial banks’ excess reserves facilitated the rapid expansion of credit. The link between money supply and other determinants of growth is not an automatic process. However, if we abide by the principles of the transmission mechanism, we might argue that the increase in money supply in Ethiopia might have contributed to an increase in investment. However, the problem of inflation in the Ethiopian economic environment cannot be tackled without addressing the large budget deficit.

More signs are appearing to suggest that what the EPRDF says regarding the economic development is incredible. For instance, recently, the Ministry of Finance & Development (MoFED) blamed the Central Statistics Agency (CSA) for its inefficiency in providing accurate data. This accusation is long overdue. An agency which cannot determine the size of population can never be trusted to give us the accurate measure of a relatively complicated matter – growth. At the time when the price of everything was doubling and tripling within a year, the inflation rate instead of being 200pc or 300pc or even more, the same statistics agency reported a much lower inflation rate. This rate is the basic component in calculating the economic development. In order to determine the change in growth, the value of domestic production has to be discounted at the current rate of inflation. If the rate of inflation assumed in discounting is far less than the actual rate, a country will, wrongly, be considered to have registered a higher rate than the actual. This is how, against World Bank and IMF predictions and the economic reality of the world, which is slowly hitting the third world, the authorities are telling us the country will register double digit growth again. While the majority of the population is getting poorer and poorer every year, a minority of the population, especially those loyal to the ruling party, are becoming millionaires overnight. The exaggerated economic development rhetoric of EPRDF is unsubstantiated for it is not based on facts and is against what is happening on the ground. It is simply a means to cover up the unspeakable atrocities they are inflicting up on the people. The inflation that we, ordinary people, are suffering from is mainly their own making. EPRDF companies and their affiliates, of course, have hugely benefitted from the manipulation and exploitation of the very thing that made our life worse and worse, inflation. So this talk of double digit economic development is simply a joke and a bluff. If Ethiopia is to achieve long-term sustainable growth, its developmental process has to be rooted in the Ethiopian system of thought and its people-centered approach, rather than depending on the Western capitalist or Chinese models of industrialisation by invitation to gain various forms of external assistance. Since agriculture is the backbone of the Ethiopian economy, its sustainable development model must be one of self-sufficiency to feed its own people instead of producing environmentally insensitive horticultural products to amass foreign currency.

Contrary to expectations, given the resources and techniques of production, the Ethiopian agricultural sector seems to have exhausted its productivity growth. To improve productivity under these conditions would require substantial investment in research and development. For example, since deforestation, desertification, increase in population, shortage of water, and air-related disease are to a large extent the symptoms of poverty, the poor need to be organised to formulate and implement their own development strategies and ensure that their basic needs are fulfilled. If policymaking is to be based on land security and adhering to environmentally-sensitive, cooperative systems, it is reasonable to assume that Ethiopia would not only achieve growth and equity (with full employment and modest inflation) but could also empower the Ethiopian people to fully participate in the design and management of long-lasting development paradigms. *Eidmon Tesfaye He Is an Expert With Master’s Degree in Agricultural Economics & Rural Development (aerd); He Can Be Contacted Via:Edimondrdae@gmail.com Source: http://allafrica.com/stories/201504071221.html

Posted by OromianEconomist in Amnesty International's Report: Because I Am Oromo, Corruption in Africa, Ethiopia the least competitive in the Global Competitiveness Index, Ethiopia's Colonizing Structure and the Development Problems of People of Oromia, Afar, Ogaden, Sidama, Southern Ethiopia and the Omo Valley, Free development vs authoritarian model, Uncategorized.

Tags: Afar, Africa, African Studies, Because I am Oromo, Developing country, Development and Change, Ethiopia's Colonizing Structure and the Development Problems of People of Oromia, Free development vs authoritarian model, Genocide against the Oromo, Governance issues, Human rights violations, Land grabs in Africa, Ogaden, Oromia, poverty, Sidama, Southern Ethiopia and the Omo Valley, State and Development, Tyranny

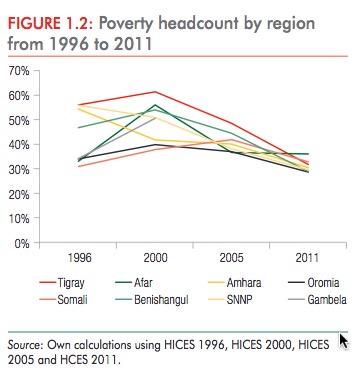

Tigray first

The answer is clear: it is the people of Tigray, whose party, the TPLF led the fight against the Mengistu regime and took power in 1991, who benefited most. What is also striking is that the Oromo (who are the largest ethnic group) hardly benefited at all.

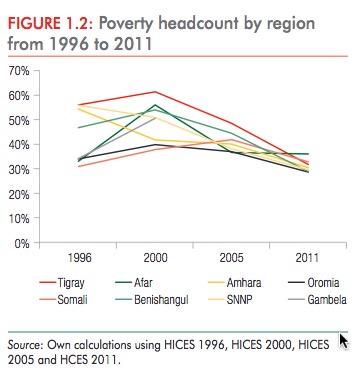

This is what the World Bank says about this: “Poverty reduction has been faster in those regions in which poverty was higher and as a result the proportion of the population living beneath the national poverty line has converged to around one in 3 in all regions in 2011.”

The World Bank does little to explain just why Tigray has done (relatively) so well, but it does point to the importance of infrastructure investment and the building of roads. It also points to this fact: “Poverty rates increase by 7% with every 10 kilometers from a market town. As outlined above, farmers that are more remote are less likely to use agricultural inputs, and are less likely to see poverty reduction from the gains in agricultural growth that are made. The generally positive impact of improvements in infrastructure and access to basic services such as education complements the evidence for Ethiopia that suggests investing in roads reduces poverty.”

Not surprisingly, the TPLF under Prime Minister Meles Zenawi and beyond concentrated their investment on their home region – Tigray. The results are plain to see.

Martin Plaut

Martin Plaut

The World Bank has just published an authoritative study of poverty reduction in Ethiopia. The fall in overall poverty has been dramatic and is to be greatly welcomed. But who has really benefited?

This is the basic finding:

In 2000 Ethiopia had one of the highest poverty rates in the world, with 56% of the population living on less than US$1.25 PPP a day. Ethiopian households experienced a decade of remarkable progress in wellbeing since then and by the start of this decade less than 30% of the population was counted as poor.

There are of course many ways of answering the question – “who benefited” – were they men or women, urban or rural people. All these approaches are valid.

The Ethnic Dimension

But in Ethiopia, where Ethic Federalism has been the primary driver of government policy one cannot ignore the ethnic dimension.

Here this graph is particularly telling:

View original post 234 more words

Posted by OromianEconomist in Africa, Africa and debt, Africa Rising, African Poor, Agriculture, Aid to Africa, Colonizing Structure, Corruption in Africa, Economics, Economics: Development Theory and Policy applications, Ethiopia the least competitive in the Global Competitiveness Index, Theory of Development, Trade and Development, Uncategorized.

Tags: Africa, African Studies, Comparative Advantage, Developing country, Development, Development and Change, economics, Trade and Development

” The benefits of trade have been well documented throughout history. The economic case is quite straightforward. Opening up to trade allows countries to shift their patterns of production, exporting goods that they are relatively efficient at producing and importing goods at a lower price that they can’t produce resourcefully at home. This lets resources to be allocated more efficiently allowing a nation’s economy to grow. Fruits of trade can be seen in many countries. In the last 30 years, trade has grown around 7% per year on average (WTO, 2013). During this time period, developing nations have seen their share in world export increase from 34% to 47% (WTO, 2013) which at first glance seem incredible. However if we dig a little deeper, it is quickly apparent that China is the key reason for the majority of the growth and that a bulk of these developing countries aren’t benefiting fully from international trade. Why is this? Many developing countries depend on the export of a few primary products and in some cases a single primary commodity for the majority of their export earnings. In fact, 95 of the 141 developing countries rely of the export of commodities for at least 50% of their export income (Brown, 2008). This is where the problem starts. Prices in the primary good’s market tend to be highly volatile sometimes varying up to 50% in a single year (South Centre, 2005). Often, the fluctuation of these products are out of the hands of the developing countries as they individually have only a small portion of the world supply which is not enough to affect world prices. At the same time, some shocks (ie. Weather) are unpredictable. The unstable commodity price brings uncertainty, instability and often negative economic consequences for the developing countries. This also affects the policymaking in the country as it is hard to implement a sustainable development scheme or a fiscal expansionary policy with uncertain revenue. Positive shocks do increase income in the short run however a study by Dehn (2000) found that there are no permanent effect on the increase on income in the long run. Furthermore, there is often very little scope to growth through primary products as it is very hard to increase volumes of sale. This is due to the demand being inelastic. The over dependence on the export of primary products also causes another problem – a risk of a large trade deficit. Several studies (Olukoshi, 1989, Mundell, 1989) have shown that primary commodity prices are the main cause for the debt problems in many developing countries. In an empirical research done by Swaray (2005), he shows the main reason behind this is the deteriorating terms of trade, developing countries face. Terms of Trade is equal to the value of export over the value of import. Over time there has been a general trend of primary products falling in value. 41 of 46 leading commodities fell in real value over the last 30 years with an average decline of 47% in real prices, according to the World Bank (cited in CFC, 2005). This has occurs due to inelastic demand for commodities and lack of differentiation among producers hence making it a competitive market. The creation of synthetic substitutes has also suppressed prices. At the same time, manufacturing products (which generally developing countries tend to import) see a general rise in prices. Put these trends together, over time, developing countries have seen their terms of trade worsen. A study by CFC (2005), shows that the terms of trade have declined as much as 20% since the 1980s. This, alongside the difficulty to increase volumes of sales has meant many developing countries have a trade deficit. According Bhagwati (1958), it is possible that this decline in the terms of trade could result in diminished welfare. In other words, growth from trade can be negative rather than positive. ”

http://randomrantsandnews.wordpress.com/2014/10/27/why-many-developing-countries-seem-contrary-to-what-the-traditional-theories-suggest-not-benefiting-from-international-trade/

Just a bit of Economics

Just a bit of Economics

The benefits of trade have been well documented throughout history. The economic case is quite straightforward. Opening up to trade allows countries to shift their patterns of production, exporting goods that they are relatively efficient at producing and importing goods at a lower price that they can’t produce resourcefully at home. This lets resources to be allocated more efficiently allowing a nation’s economy to grow. Fruits of trade can be seen in many countries. In the last 30 years, trade has grown around 7% per year on average (WTO, 2013). During this time period, developing nations have seen their share in world export increase from 34% to 47% (WTO, 2013) which at first glance seem incredible. However if we dig a little deeper, it is quickly apparent that China is the key reason for the majority of the growth and that a bulk of these developing countries aren’t benefiting fully…

View original post 1,047 more words

Posted by OromianEconomist in Africa and debt, Africa Rising, African Poor, Agriculture, Aid to Africa, Corruption in Africa, Ethiopia the least competitive in the Global Competitiveness Index, Ethiopia's Colonizing Structure and the Development Problems of People of Oromia, Free development vs authoritarian model, The extents and dimensions of poverty in Ethiopia, The State of Food Insecurity in Ethiopia.

Tags: African Studies, Hunger and Micronutrient deficiency in Ethiopia, Povertry, State and Development, Sub-Saharan Africa, Tyranny and Famine, Undernourishment in Ethiopia

The ‘hidden hunger’ due to micronutrient deficiency does not produce hunger as we know it. You might not feel it in the belly, but it strikes at the core of your health and vitality.

– International Food Policy Research Institute

Ethiopia and its Hidden Hunger in the Shadows of Fastest Economic Growth Hype

Ethiopia is making the 7th worst country (marked alarming) in Global Hunger Index (GHI) 2014. It is the 70th of the 76 with GHI score of 24.4 and Proportion of undernourished in the population (%) 37.1. http://www.ifpri.org/tools/2014-ghi-map

The 10 worst countries in 2014 GHI Score are: Ethiopia, Chad, Sudan/South Sudan, East Timor-Leste, Comoros, Eritrea, Burundi, Haiti, Zambia and Yemen.

http://www.ifpri.org/sites/default/files/publications/ghi14.pdf

According to the IFPRS report 2014 which was released on 13th October, more than 2 billion people worldwide suffer from hidden hunger, more than double the 805 million people who do not have enough calories to eat (FAO, IFAD, and WFP 2014). Much of Africa South of the Sahara and South Asian subcontinent are hotspots where the prevalence of hidden hunger is high. The rate are relatively low in Latin America and the Caribbean where diets rely less on single staples and are more affected by widespread deployment of micronutrient interventions, nutrition education, and basic health services.

Definitions:

- Hunger: distress related to lack of food

- Malnutrition: an abnormal physiological condition, typically due to eating the wrong amount and/or kinds of foods; encompasses undernutrition and overnutrition

- Undernutrition: deficiencies in energy, protein, and/or micronutrients Causes include poor diet, disease, or increased micronutrient needs not met during pregnancy and lactation

- Undernourishment: chronic calorie deficiency, with consumption of less than 1,800 kilocalories a day, the minimum most people need to live a healthy, productive life

- Overnutrition: excess intake of energy or micronutrients

- Micronutrient deficiency (also known as hidden hunger): a form

of undernutrition that occurs when intake or absorption of vitamins and minerals is too low to sustain good health and development in children and normal physical and mental function in adults

- Undernourishment: chronic calorie deficiency, with consumption of less than 1,800 kilocalories a day, the minimum most people need to live a healthy, productive life

- Overnutrition: excess intake of energy or micronutrients

Read the Full report @ http://www.ifpri.org/sites/default/files/publications/ghi14.pdf

Posted by OromianEconomist in African Internet Censorship, Ethiopia the least competitive in the Global Competitiveness Index, Facebook and Africa.

Tags: African Studies, Internet Poverty, People without Internet

4.4 billion people around the world still don’t have Internet. Here’s where they live

October 3, 2014 (Washington Post) — The world wide web still isn’t all that worldwide.

An exhaustive newstudy by McKinsey & Company (really, it’s 120 pages long) about the barriers to Internet adoption around the world illuminates a rather surprising reality: 4.4 billion people scattered across the globe, including 3.2 billion living in only 20 countries, still aren’t connected to the Internet.

The sheer number of people unconnected in some countries is staggering. India is home to nearly a quarter of the world’s offline population; China houses more than 730 million; Indonesia 210 million; Bangladesh almost 150 million; and Brazil nearly 100 million. Even in the United States, 50 million people don’t use the Internet (though, as my colleague Caitlin Dewey points out, many of those who are offline in the United States are offline by choice).

But adjusting for size, and instead looking at the percentage of people in certain countries that still aren’t connected to Internet, shows that quite a few places have very little internet penetration at all. In Myanmar, 99.5 percent of the population is offline; in Ethiopia, almost 98 percent; in Tanzania, more than 95 percent; and in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, just under 95 percent.

Most of the world’s offline population, some 64 percent, live in rural settings, where poor infrastructure, health care, education, and employment, impede Internet adoption, the study says. In India, for instance, roughly 45 percent of the population lives without electricity, making Internet access all the more unthinkable.

http://ayyaantuu.com/horn-of-africa-news/4-4-billion-people-around-the-world-still-dont-have-internet-heres-where-they-live/

Posted by OromianEconomist in Africa, Africa and debt, Africa Rising, African Poor, Ethiopia & World Press Index 2014, Ethiopia the least competitive in the Global Competitiveness Index, Ethiopia's Colonizing Structure and the Development Problems of People of Oromia, Ethiopia's Colonizing Structure and the Development Problems of People of Oromia, Afar, Ogaden, Sidama, Southern Ethiopia and the Omo Valley, Food Production, Free development vs authoritarian model, Genocidal Master plan of Ethiopia, Illicit financial outflows from Ethiopia, Poverty, The extents and dimensions of poverty in Ethiopia, The Global Innovation Index, The State of Food Insecurity in Ethiopia, The Tyranny of Ethiopia, US-Africa Summit, Youth Unemployment.

Tags: African Studies, Development and Change, Genocide against the Oromo, Governance issues, poverty, State and Development, The State of Food Insecurity in Africa, The State of Food Insecurity in Ethiopia, Universal Declaration of Human Rights

The absolute number of hungry people—which takes into account both progress against hunger and population growth—fell in most regions. The exceptions were Sub-Saharan Africa, North Africa, and West Asia.

The 2014 FAO’s report which is published in September indicates that while Sub-Saharan Africa is the worst of all regions in prevalence of undernourishment and food insecurity, Ethiopia (ranking no.1) is the worst of all African countries as 32 .9 million people are suffering from chronic undernourishment and food insecurity. Which means Ethiopia has one of the highest levels of food insecurity in the world, in which more than 35% of its total population is chronically undernourished.

Ethiopia is one of the poorest countries in the world, ranking 173 of the 187 countries in the 2013 Human Development Index.See @ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_Human_Development_Index

FAO in its key findings reports that: overall, the results confirm that developing countries have made significant progress in improving food security and nutrition, but that progress has been uneven across both regions and food security dimensions. Food availability remains a major element of food insecurity in the poorer regions of the world, notably sub-Saharan Africa and parts of Southern Asia, where progress has been relatively limited. Access to food has improved fast and significantly in countries that have experienced rapid overall economic progress, notably in Eastern and South-Eastern Asia.Access has also improved in Southern Asia and Latin America, but only in countries with adequate safety nets and other forms of social protection. By contrast, access is still a challenge in Sub Saharan Africa, where income growth has been sluggish, poverty rates have remained high and rural infrastructure remains limited and has often deteriorated.