Posted by OromianEconomist in Africa, Ancient African Direct Democracy, Ancient Rock paintings in Oromia, Ateetee, Ateetee (Siiqqee Institution), Black History, Chiekh Anta Diop, Culture, Irreecha, Kemetic Ancient African Culture, Meroe, Meroetic Oromo, Oromia, Oromiyaa, Oromo, Oromo Culture, Oromo Identity, Oromo Nation, Oromo Wisdom, Oromummaa, Philosophy and Knowledge, Qaallu Institution, Qubee Afaan Oromo, Sirna Gadaa, State of Oromia, The Oromo Democratic system, The Oromo Governance System, The Oromo Library.

Tags: Afaan Oromo, Africa, African culture, African history, African Studies, Ancient Paintings in Oromia, Ateetee, Civilization, Gadaa System, Oromia, Oromiyaa, Oromo, Oromo culture, Oromo people, Oromummaa, Qaalluu Institution

Qaallu Institution: A theme in the ancient rock-paintings

of Hararqee—implications for social semiosis and

history of Ethiopia

Dereje Tadesse Birbirso (PhD)*

International Journal of Archaeology Cultural Studies Vol. 1 (1), pp. 001-018, September, 2013. Available online at http://www.internationalscholarsjournals.org © International Scholars Journals

This article critically analysed some of the ancient rock paintings of Hararqee of Eastern Oromia/Ethiopia with the intention to understand and explain the social epistemological and rhetorical structures that underlie beneath these social ‘texts’. It did so through using sub-themes in the ancient Qaallu Institution of the Oromo as analytical devices. Multi-disciplinary approach that combined concepts from various disciples was adopted as a guiding theoretical framework, while the Eurocentric approach that de-Ethiopinizes these historic heritages was rejected. Field data was collected from various sites of ancient rock paintings in Hararqee. Archival data

were also collected. Two informants expert with wisdom literature were selected in order to consolidate the multi-disciplinary approach adopted with the interpretive framework of the traditional, local social epistemology. The results of the analysis revealed both substantive and methodological insights. Substantively, it suggests that the Oromo Qaallu Institution fundamentally underlies the social semiotic, linguistic and epistemological structures communicated by means of the rock painting signs or motifs. Some of these are the Oromo pre-Christian belief in Black Sky-God, pastoral festival in the praise of the cattle and the

fecundity divinity and genealogico-politico-identification structures. Methodologically, the unique Oromo social semiotical and stylystical rhetorics which could be referred as ‘metaplasmic witticism’ and the role of Qaallu Institution sub-themes as sensitizing devices and the emergent directions for future research are all presented in this report.

INTRODUCTION

Hararqee, the vast land in Eastern Ethiopia, is where over 50% of Ethiopia’s (possibly including Horn of Africa)

rock paintings are found (Bravo 2007:137). Among these is the famous Laga Oda Site “dating to at least 16,000

BP” (Shaw and Jameson 1999:349) and comprising depictions of bovines and many different types of animals. This vast land of Hararqee is settled by the Oromo, the largest tribe of the Cushitic stock, and hence it is part of the Oromia National State. The Oromo people, one of the richest in ancient (oral) cosmogonal- social history , literature and especial owners of the unique socio-philosophico-political institution known as Gada or Gada System, consistently insist that theirs as well as human being’s origin is in the Horn of Africa specifically a place known as Horra βalabu/Ŵolabu ‘the Place of Spring-Water of Genesis of Humanity’ (Dahl and Megerssa 1990).

This and a plethora of Oromo social epistemology has been studied by the plausible Oromo historians (Gidada 2006, Hassen 1990, to mention a few) and non-biased European theologico-ethnologists (Krapf 1842; De Abbadie 1880; De Salviac 1980, Bartels 1983, to mention a few). Similarly, social semiosis is not new to the Oromo. Although Eurocentric archaeologists rarely acknowledge, “the identification of cultural themes and symbolic interpretation has revealed affinities between contemporary Oromo practices and those of other East African culture groups, both ancient and modern (Grant 2000: np.).In like manner, the Classical Greek philosophers wrote that the Ancient Ethiopians were “inventors of worship, of festivals, of solemn assemblies, of sacrifice, and of every religious practice” (Bekerie, 2004:114). The oral history of the Oromo states that it was Makko Billii, whom Antonio De Abbadie, one of the early European scholars who studied and lived with the Oromo, described as “African Lycurgus” (Werner 1914b: 263; Triulzi and Triulzi 1990:319; De Abbadie 1880) and son of the primogenitor of the Oromo nation (Raya or Raâ), who hammered out the antique, generation-based social philosophy known as Gada System (Legesse 1973, 2006; Bartels 1983; Gidada 2006). A key ingredient in Gada system is the For Oromo, the first Qaallu “Hereditary ritual officiant” and “high priest” was of “divine origin” and, as the myth tells us, “‘fell from the sky itself’…with the first black cow” and he was the “‘eldest son of Ilma Orma’” (Hassen 1990:6; Baxter, Hultin and Triulzi 1996:6). In its “dual[ity] nature”, Waaqa, the black Sky-God “controlled fertility, peace, and lifegiving rains… [hence] prayers for peace, fertility, and rain” are the core recursive themes in Oromo religion (Hassen 1990:7). Hence, the concept/word Qaallu refers at large to “Divinity’s fount of blessings in the world” (Baxter, Hultin and Triulzi 1996: 1996: 21). As De Salviac (2005 [1901]: 285) explicated “The Oromo are not fetishists. They believe in Waaqa took, a unique universal creator and master. They see His manifestations in great forces of nature, without mistaking for Him.” As a result of this ‘pre-historic’, Spinozaean like social epistemology, but unlike Martin Heideggerean “ancients” who never dared questioning or confronting ontology but endorsed only veneering it, for the Oromo social semiosis has never been new since time immemorial. Despite all these antique history and tradition, it is unfortunatel, the so-far few studies made on the Ethiopian ancient rock paintings and rock arts never consider—sometimes apparently deliberately isolate–the social history, tradition, culture or language of the Oromo people as a possible explanatory device. What the available few studies usually do is only positivist description of the paintings (types, size and/or number of the signs) rather than inquiry into and explanation of the social origin and the underlying social meaning, praxis or worldview. Partly, the reason is the studies are totally dominated by Eurocentric paradigms that de-Africanize and extrude the native people and their language, religion, social structure, material cultures and, in general, their interpretive worldview. Besides, some of the native researchers are no different since they have unconditionally accepted this Eurocentric, hegemonic epistemology (Bekerie 1997; Smith 1997; Gusarova 2009; Vaughan 2003). As a result, we can neither understand the social origin of these amazing ‘texts’ nor can we explain the underlying social semiosis.. Equally, under this kind of mystification or possible distortion of human (past) knowledge, we miss the golden opportunities that these ancient documents offer for evolutionary, comparative and interdisciplinary social science research and knowledge. Above all, the old Eurocentric view narrowed down the sphere of semiotics (archaeological, social) to only ‘the sign’, extruding the human agents or agency and the social context.

The aim of this paper is to use the ancient Qaallu Institution of Oromo as analytical ‘devices’ in order to understand and explain the underlying social epistemological, semiotical and rhetorical structures, i.e., expressed in all forms of linguistic and non-linguistic structures. In sharp contrast to the aforementioned positivist, narrow, colonial semiotics, in this analysis,

Theo van Leeuwen’s postmodern and advanced approach to social semiotics is adopted. Primarily, Van Leeuwen (2005: 3) expands “semiotic resource” as involving “the actions and artefacts we use to communicate, whether they are produced physiologically – with our vocal apparatus…muscles…facial expressions and gestures, etc. – or by means of technologies – with pen, ink and paper…computer hardware and software…with fabrics, scissors and sewing machines.”

Van Leeuven (2005: xi) introduces the changing semiosphere of social semiotics:

Just as in linguistics the focus changed from the ‘sentence’ to the ‘text’ and its ‘context’, and from

‘grammar’ to ‘discourse’, so in social semiotics the focus changed from the ‘sign’ to the way people use semiotic

‘resources’ both to produce communicative artefacts and events and to interpret them;

Rather than constructing separate accounts of the various semiotic modes – the ‘semiotics of the image’, the ‘semiotics of music’, and so on – social semiotics compares and contrasts semiotic modes, exploring what they have in common as well as how they differ, and investigating how they can be integrated in multimodal artefacts and events.

Indeed, the Classical Western dualism which separates the linguistic from the non-linguistic, the literary from the

non-literary, the painting from the engraved, the notional from the artefactual must be eschewed, especially when

we build evolutionary perspective to analyzing pre-historic arts.

CLEARING SOME CONFUSIONS

Scholars have already explicated and explained away the old de-Ethiopianization historiographies in social sciences

(Bekerie 1997; Smith 1997; Gusarova 2009; Vaughan 2003), humanities (Ehret 1979) and archaeology

(Finneran 2007). Therefore, there is no need to repeat this here. But, it is necessary to briefly show disclose some

veils pertaining to Hararqee pre-historic paintings. As usual, the ‘social’ origin of ‘pre-historic’, Classical or Medieval era Hararqee rock paintings is either mystified or hailed as agentry “Harla” or “Arla” (Cervicek and Braukämper 1975:49), an imaginary community:

According to popular beliefs Harla generally refers to a mysterious, wealthy and mighty people, (frequently even

imagined as giants!), who had once occupied large stretches of the Harar Province before they were destroyed by the supernatural powers through natural catastrophies as punishment for their inordinate pride. This occurred prior to the Galla (Oromo) incursions into these areas during the 16th and 17th centuries” (Cervicek and Braukämper 1975: 49; emphasis added).

In footnote, Cervicek and Braukämper (1975:49) quote Huntingford (1965:74) to on the identity of the Harla: “The

name “Harla” is first mentioned, as far as we know, in the chronicle of the Ethiopian Emperor ‘Amda Seyon in the

14th century (Huntingford 1965:74).” It is clear that this mystification prefigures in the usual gesture of de-Africanizing civilization of Black Africans to justify the so-called Hamitic myths, as explained well in the works of the aforementioned post-modern scholars. Thanks to Professor Claude Sumner (Sumner 1996: 26), today we know the fact of the matter, that it was not Huntingford who composed about the imaginary “Harla”. It was the French Catholic missionaries by the name

François Azais and Roger Chambard who reconstructed to fit it to their interest the imaginary ‘Harla’ (spelling it

rather as “Arla”) from an oral history told to them by an Oromo old man from Alla clan of Barentuu.The story itself

is about a “wealthy” Oromo man called “Barento” who was “very rich but very proud farmer” (Sumner 1996: 26).

For it is both vital and complex (in its ironic message, which cannot however be analyzed here) we have to

quote it in full:

There was in the Guirri country, at Tchenassen [Č’enāssan], an Oromo, a very rich but very proud farmer called Barento. A cloth merchant, an Arab who was also very rich, lived a short distance from there at Derbiga. The merchant’s daughter went one day to see the farmer and told him: “I would like to marry your son.”—“Very well, I shall give him to you,” he answered. The merchant in turn, gave his daughter and made under her daughter’s steps a road of cloth, from Derbiga to Tchenassen, residence of the rich farmer. The tailor replied to this act by making a road of dourah and maize under his son’s steps, from Tchenassen to Derbiga. But God was incensed by this double pride and to punish him, shaked Tchenassen Mountain and brought down a rain of stones which destroyed men and houses; it was then that the race of Arla [Alla] was destroyed (Sumner 1996: 26). Confirming the antiquity and unity of this story and the Oromo, similar story is found in Western Oromo as far closer to the Southern Sudan: “in interpreting certain of their [Oromo] myths about the beginning of things, it was because of man’s taking cultivation and pro-creation toomuch into his own hands, that Waqa[Waaqa] withdrew from him–a withdrawal resulting in a diminution of life on earth in all its forms” (Bartels 1975:512). As a part of the general social semiotics adopted in this study, onomasiology (the scientific analysis of toponyms, anthroponyms,ethnonyms as well as of semiotic metalanguages) is considered as important component for evolutionary social semiosis, particularly for any researcher on Oromo since these are coded or they code social epestemes, are cyclical, based on the principles of Gada System’s name-giving tradition, and, hence, are resistant to change (for detail on this see Legesse 1973). For instance, Cervicek and Braukamper (1965:74) described the Laga Gafra area and its population as: “The area of the site is part of the Gafra Golla Ḍofa village, and the indigenous Ala [Oromo] call it Gada Ba’la (“large shelter”)”, but appropriately, Baalli Gada. Here, let us only remember that Alla and Itťu clans are two of the Hararqee Oromo self-identificating by Afran Qalloo

(literally the Quadruplets, from ancient sub-moiety) who “provide[d] a basis for…construct[ing] models for

prehistoric land and resource use” (Clark and Williams:

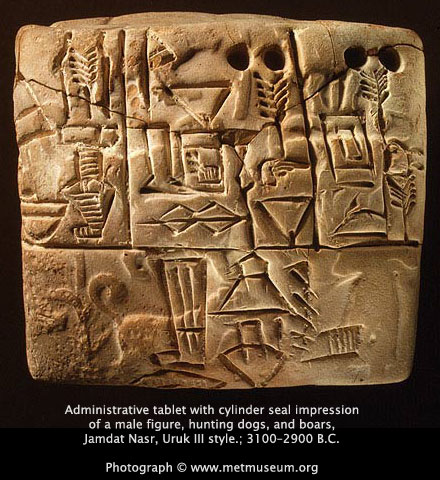

Social semiosis, language and reality in the ancient ‘texts’ Social semiosis might be considered as old as homo

sapiens sapiens. But, for our analytical purpose, it is logical to begin from the Ancient Black Africans that some

19th century European missionaries and researchers referred to as ‘Ancient Egyptians’ (although still others

refer to them by Ancient Cushites, Ancient Ethiopians, Ancient Nubians or Meroes), who are the originators of

the first writing systems known as ‘hieroglyphics’. Chiekh Anta Diop (Diop 2000), Geral Massey (Massey 1907)

and other scholars have illuminated to us a lot about hieroglyphics. Initially, hieroglyphics was pictogram or semagram. That is, pictures of real world were ‘painted’ to communicate a sememe or motif, the smallest meaningful structure or concept, for instance, a picture of sitting man for their word equivalent to the English ‘sit’; a picture of man stretching his/her arms to the sky for ‘pray’; a lion for ‘great man’, etc., all or some of which is determined by

the lexical structures (phonological, syllabic, semantic, imagery they arise, etc) of their respective words. Based

on their social philosophy/paradigm, literary/figurative symbolism, and/or their word’s/language’s phonology/syntax, for instance, equivalent to the English ‘woman’, they might have also depicted a picture of a pigeon, or an owl or a cow. This zoomorphic mode of representation as the ‘Sign-Language of Totemism and Mythology’ was the first and early writing system in human history. The Ancient Egyptians used the principles of, among others, sound-meaning association, semantic and ontologic (what something/somebody can cause) similarization, physical resemblance, grouping (duplication or triplication of the same pictograms to represent meaning), aggregation (pictograms are combined in or around a spot or a pictogram is duplicated as many as necessary and congregated in or around a spot), sequencing vertically or horizontally (representing lexico-grammatic, syntactic, semotactic or stylistic structure) and so forth.

Some of these or similar principles or ‘stylistic features’ are observed, particularly, in the Laga Oda painting styles. Cervicek (1971:132-133 122-123), for instance, observed in Laga Oda paintings such stylized ‘discourse’ as ‘group of horseshoe-like headless bovine motifs’, ‘paired ‘soles of feet’ from Bake Khallo [Bakkee Qaallu ‘Sacred Place for Qaallu Ritual]’, ‘oval symbo accompanied as a rule by a stroke on their left side’, sun-like symbol, in the centre with animal and anthropomorphic representations grouped around it’, paired ‘soles of feet’, carefully profiled styles (overhead, side, back point-of-view of bovines), zooming (large versus small size of bovine motifs), headless versus headed bovines, H-shaped anthropomorphic

representations with raised hands’, superimposition and so forth. Any interpretation that renders these as isolated

case, arbitrary or pointless marks can be rejected outright. Some of these ‘early spelling’ are found not only across the whole Horn of Africa but also in Ancient Meroitic-Egyptian rock paintings, hieroglyphics and, generally, organized social semiosis.By the same token, Oromo social semiotical ‘texts’, like any ancient texts, textures “intimate link…between form,

content and concrete situation in life” (Sumner 1996:17-18). Professor Claude Sumner, who produced three volume analysis of Oromo wisdom literature (Sumner 1995, 1996, 1997), sees that like any “ancient texts”, in Oromo wisdom literature, “a same unit of formal characters, namely of expressions, of syntactic forms, of vocabulary, of metaphors, etc., which recur over and over again, and finally a vital situation…that is a same original function in the life of [the people]” (Sumner 1996:19). An elderly Oromo skilled in Oromo wisdom speaks, to use the appropriate Marxian term, ‘historical materialism’, or he speaks “in ritual language, as it was used in old times at the proclamation of the law” (Bartels 1983:309).

Moreover, he speaks in rhythmatic verses, full of “sound parallelism” (Cerulli 1922), “parallelism of sounds” or

“image” or “vocalic harmony” (Bartels 1975: 898ff). Even Gada Laws used to be “issued in verse” (Cotter 1990:

70), in “the long string of rhyme, which consists of repeating the same verse at the end of each couplet” or “series of short sententious phrases” that are “disposed to help memory” (De Salviac 2005 [1901]: 285). The highly experienced researchers on the ancient Oromo system of thought, which is now kept intact mainly by the Booran Gada System, emphasize that “‘the philosophical concepts that underlie the gadaa system’…utilize a symbolic code much of which is common to all Oromo” (Baxter, Hultin and Triulzi 1996: 21). Long ago, one scholar emphatically stated, this is a feature “surely has developed within the [Oromo] language” and “is also only imaginable in a sonorous language such as Oromo” which “as a prerequisite, [has] a formally highly developed poetical technique” (Littmann 1925:25 cited in Bartels 1975:899).

Claude Sumner formulates a “double analogy” tactic as prototypical feature of Oromo wisdom literature, i.e., “vertical” and “horizontal” parallelism style (Sumner 1996:25), known for the most part to linguists, respectively, as ‘paradigmatic’ (‘content’ or ‘material’) and ‘syntagmatic’ (‘form’ or ‘substance’) relations or in both literature and linguistics, as contextual-diachronic and textual-synchronic, relations. Oromo social epistemological concepts/words/signs offers important data for historical and evolutionary social sciences for they recycle and, consequently, are resistant to change both in form and meaning (Legesse 1973). In the same way, in this analysis of the ancient rock paintings of Hararqee, an evolutionary and multidisciplinary analysis of the interrelationship among the traditional ‘semiotic triangle’—the sign (sound or phonon, word or lexon, symbol or image), the signified (the social meaning, ‘semon’, episteme or theme) and the referent (cultural-historical objects and ritual-symbolic actions)——and among the metonymic complex (referring here to layers and clusters of semiotic triangles in their social-natural contexts) is assumed as vital meta-theoretical framework.

METHODS AND THE SEMIOTIC RESOURCES

For this analysis, both archival and field data or semiotic resources are collected. In 2012 visits were made to the

some of the popular (in literature) ancient rock painting sites in Hararqee (Laga Oda, Goda Agawa, Ganda Biiftu,

etc.; comprehensive list of Ethiopian rock painting sites is presented by Bravo 2007). Also, field visits were made to

less known (in literature) ancient to medieval era painting sites were made in the same year (e.g., Goda Rorris,

Huursoo, Goda K’arree Ǧalɖeessa, Goda Ummataa, Goda Daassa, etc). Huge audiovisual data (still and

motion) of both paintings and engravings were collected, only very few of which are used in this paper. On the one

hand, the previously captured data (as photos, sketches or traces) from some of the popular sites, for instance

Laga Oda and Laga Gafra (as in Cervicek 1971; Cervicek and Braukamper 1975), are sometimes found to be

preferably clearer due to wear-off or other factors. On the other hand, from the same sites, some previously

unrevealed or undetected motifs (painted or engraved) were collected. Therefore, both field and archival data are

equally important for this analysis. However, since the Qaallu Institution , and its sub-themes, is used as sensitizing device or a means rather than end— hence is capitalization upon social semiotic and linguistic aspects–there is an inevitable risk of undermining these complex philosophical notions. Yet, for the pertinent (to Qaallu Institution) anthropological-ethnological archivals used as additional secondary data or, to use Theo van Leeuwen’s term, as “semiotic resource”, original and influential references are indicated for further reading. More importantly, two old men skilled in Oromo social epistemology, customarily referred to as ‘walking libraries’, are used as informants. Taaddasaa Birbirsoo Mootii, 87, from Wallagga, Western Oromia (Ethiopia) and Said Soddom Muummee, 85, from Hararqee Eastern Oromia (Ethiopia). Mootii, Addoo Catholic Church Priest (‘Catechist’ is the word they use), was one of the infor- mants and personal colleagues of Father Lambert Bartels, who studied in-depth and wrote widely on Oromo religion, rituals and social philosophy. His scholarly and

comparative (with Biblical) analysis of Oromo religion and world view, child birth custom, praise song for the cow,

Qaallu Institution, Gada system geneaological-social hierarchy are among his seminal works. Although Bartels

only indicated Mootii as “one priest”, he and his colleague Shagirdi Boko (one of the Jaarsa Mana Sagadaa ‘Old

Men of Church’) were among his informant colleagues. Muummee, is not only well seasoned wiseman, but he

still celebrates and identify himself as Waaqeeffata—believer, observer and practitioner of the pre-Christian

Oromo religion founded on Waaqa, the Black Sky-God.

ANALYSIS AND DISCUSSION

Qaallu Institution and the praise to the cattle Above, under Introduction section, we briefly touched upon the mythical-social origin of the Qaallu Institution and its relation with genesis and cow-milk. Qaallu comes from the gerundive qull (qul’qullu, intensive) ‘pure, holy, sacred, blameless; being black, pretty, neat’, pointing to the color and quality of Waaqa (see Bartels 1983; Hassen 1990 for detail).. The “ancient” Qaallu Institution of Oromo (Baxter 1987: 168 quoted and elaborated in Gidada 2005: 146-147) had been widely practiced in Eastern, Hararqee Oromo until the first half of the 20th century. It is as much cosmogonal, cosmological and ideological (identificational) as it is theo-political to the Oromo nation, in particular, and, at large, the pre-colonial (pre-Christian, pre-Islam) Cushite who uniformly believed in Water, as a source of life and on which life is unilaterally dependent, and in Waaqa–a concept/word that means, on the one hand, the abstract ‘Supreme Being, God, Devine, Heave’ and, on the other, the ‘concrete’ ‘Sky, Divinely Water (rain)’. For Oromo, the first Qaallu “a high priest”, the “spiritual leader” was of “divine origin”, as the myth tells us, “ ‘fell from the sky itself’…with the first black cow” and he was the “‘eldest son of Ilma Orma’” and in its “dual nature”, Waaqa, the black Sky-God “controlled fertility, peace, and lifegiving rains…[hence] prayers for peace, fertility, and rain” are the core recursive themes in Oromo religion (Hassen 1990: 6-7). For more on Oromo genealogical tree and history, see Gidada (2006), Bartels (1983), BATO (1998), to mention a few.

The Booran Oromo, who still retains the Qaallu

Institution ‘unspoiled’:

The Booran view of cosmology, ecology and ontology is one of a flow of life emanating from God. For them, the benignancy of divinity is expressed in rain and other conditions necessary for pastoralism. The stream of life flows through the sprouting grass and the mineral waters [hoora] of the wells, into the fecund wombs and generous udders of the cows [ɢurrʔ

ú]. The milk from the latter then promotes human satisfaction and fertility (Dahl and Megerssa 1990: 26).

In this worldview, the giant bull (hanɡafa, hancaffa) is a symbol of angaftitti “seniority of moieties: stratification

and imbalance” (Legesse 2000: 134). Hence, the separation of the most senior or ancient moieties or the cradle land imitates hariera ‘lumbar and sacral vertebrae’ (other meaning ‘queue, line, suture’) or horroo ‘cervical vertebrae’ of the bull.

The primogenitors (horroo) of the Oromo nations (mainly known as Horroo, Raya, Booro) set the first ßala ‘moiety, split (from baɮ ‘to flame, impel, fly; to split, have bilateral symmetry’) or Ẃalaßu ‘freedom, bailing, springing’. The formation of moieties, sub-sub-moieties grew into baɭbaɭa‘sub-sub-sub-etc…lineages’ (also means ‘door, gate’; the reduplication showing repetitiveness). Jan Hultin, an influential anthropologist and writer on Oromo, states “Among the Oromo, descent is a cultural construct by which people conceive of their relations to each other and to livestock and land; it is an

ideology for representing property relations” (Hultin 1995: 168-169). The left hand and right hand of the bovine always represent, in rituals, the “sub-sections of the phratry” (Kassam 2005:105). That is, as the tradition sustains,

when the ancient matrilineal-patrilineal moieties sowed, dissevered (fač’á) from the original East (Boora), the

Booreettúma (designating matrilineality, feminine soul) took or went towards the left hand side, while the Hoorroo

(also for unclear reason βooroo, designating patrilineality, masculine soul) took the right hand side. Both correspond, respectively, to the directions of sunrise and sunset, which configure in the way house is constructed: Baa, Bor ‘the front door’ (literally ‘Origin, Beam, morning twilight’) always faces east, while the back wall (Hooroo) towards west (also Hooroo means ‘Horus, evening twilight’). This still governs the praxis that the backwall “is the place of the marriage negotiations and of the first sexual intercourse of sons and their bride [i.e., behind the stage]” (Bartels 1983: 296). For this reason, Qaallu Institution has had a special Law of the Bovine as well as Holiday of the Cattle/Bovine, Ǧaarrii Looni (Legesse 1973:96; Dahl and Megerssa 1990). On Ǧaarrii Loonii, cattle pen are renovated and embellished, and festivities and dances with praise songs to cattle was chanted (for more, Bartels 1975; Wako 2011; Kassam 2005). An excerpt from the praise song ‘talks’ about them with admiration (See also Bartels 1975: 911):

Chorus: Ahee-ee

Soloist: Sawa, sawilee koo–Cows, o my cows,

Bira watilee koo–and also you, my calves.

Ǧeɗ’e malee maali–Could I say otherwise?

Yá saa, yá saa—o cattle, o cattle!

saa Humbikooti–cattle of my Humbiland,

Saa eessa ǧibbu?–What part of cattle is useless?

Saa qeensa qičču–Our cattle with soft hoofs,

koṱṱeen šínii ta’e—from their hoofs, we make coffee-cups

gogaan wallu ta’e—from their skins, we make wallu

[leather cloth]

gaafi wanč’a ta’ee, — from their horns, we make wáɳč’a

[large beer cup]

faɭ

ʔ

anas ta’a!—as well as spoons! [See Fig.1A, B, C, D,

E]

Chorus: Ahee-ee

Lambert Bartels, a Catholic Father and scholar lived with the Oromo, writes “When they bless, they say: ɡurrači

ɡaraa ǧ’abbii siif ha kenu ‘May the dark one [God] with hail under his abdomen give you all (good things)’

(Bartels 1983:90-91). Cervicek (1971:124 Fig.10) wonders about the unexplained but recurrent “oval

representations… painted black [and] white-dotted” and consistently painted “below” the cow udder (see Fig.2B).

This can be compared with wáɳč’a ‘drinking horn-cup’ or č’óč’oo, č’iič’oo ‘milking (horn-)cup’ (see Fig.1D). On

Irreečča ritual of Thanking Waaqa the Black Sky-God, a line of the doxology mentions, among others, “Waaqa

č’iič’oo gurraattii” ‘God of the dark č’iič’oo milking-cup’ (Sabaa 2006:312). The deadjectival č’óč’orree means ‘white dotted (black background); turkey or similar white dotted bird’, while Waaɳč’ee is a proper name for white-dotted cow.

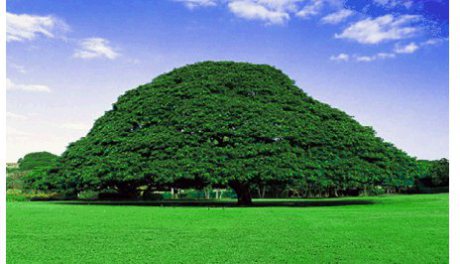

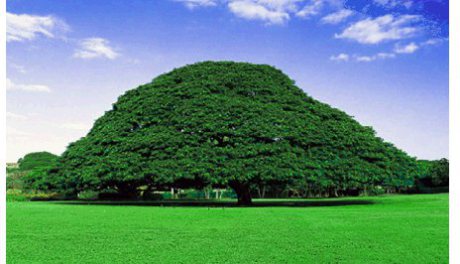

Qaallu as ecotheological concept

Qaallu is also an ontological concept referring to the spirit that resides in sacred realities, the mountain hills, seas, river

beds, pasture land, etc. As an important place for ritual place for immortalizing (primogenitors, ancestors), blessing

(children, the young), initiations (to Gada classes, power take-over), praying (for fertility, abundance, fortune, rain),

and praising (God, nature, cattle), the sacred land of spirituality must be mountain foot (goda) where there must

be, naturally, laga ‘lagoon, river’, č’affee ‘marshy area with green grasses’ (symbol of the parliamentary assembly),

χaɭoo ‘pasture land’, and the evergreen oɖaa fig sycamores. Oɖaa serves not only as “a depiction of a political power”,

but “is also a centre of social and economic activities” and “symbolizes the entire corpus of their activities, history,

culture and tradition” (Gutamaa 1997:14). Five Qaallu centres are known in Booran sub-moiety: (1) Qaallu Odiituu, (2) Qaallu Karrayyuu, (3) Qaallu Matťarii, (4) Qaallu Karaar, (5) Qaallu Kuukuu, (10) Qaallu Arsii (Nicolas 2010). These centers are like cities of (con-)federal states and simultaneously are (sub-)clan names. These names are codes and decoders of not only genealogical and landscapes, but also of ancient (sub)-moieties and settlement patterns. Since they are cyclical, based on the principles of Gada System’s name-giving principle, they are widespread across Oromia and resistant to change. Werner (1915:2) observed that in Booran Oromo, “every clan has its own mark for cattle, usually a brand (ɢuʋa [ɡuƀá ], which is the name of the instrument used, is an iron spike fixed into a wooden handle)”, a fact which is

significated in other parts of Oromia with different signifiers, for instance, pattern of settlement, which is determined by a

korma karbaʑaa ‘bull that bulldozes jungles’ or korma qallaččaa ‘kindling bull’ (Gidada 2006: 99-100) or bull’s

anatomy (BATO 1998). For instance, quoting Makko Billii, the ancient Gada System law maker, the Wallaga Oromo

recite their settlement pattern in the anatomy of Korma the virile ‘buffalo-bull’ or ‘macho man’: Sibuun garaača. Haruu č’inaacha, Leeqaan dirra sangaati, ‘The Sibuu [Sabboo] clan is the abdomen, the Haruu [Hooroo] is the ribs, and Leeqaa is the chuck of the bull’ (BATO 1998:164).

Qallačča bull as a kindler is related defined qallačča “a white patch between the horns of a cow running back down the

two sides of the neck; a charm” (Foot 1913:33). See Fig.2 A, B, C and D . It is the symbol of a Qaallu’s qallačča, here

meaning, an inherited, from ancestors, spiritual and intellectual grace or sublimity. This is quite related to of

book’a ‘a black cow or bull or ram that has a white mark upon the forehead’ (Tutschek 1844:135-136), a natural

phenomenon considered as a good omen. Adda isá book’aa qaba ‘his forehead has a blaze’ is an idiom appropriately

meaning the person has the natural capacity, inherited from ancestors, to prophesize, foreknow. For this reason, “white-headedness” or wearing white turban is a symbol of (passage to) seniority or superordinate moiety (Kassam 1999). As usual, there is “intimate link…between form, content and concrete situation in life” (Sumner 1996:17-18).

Qallačča as a mysterious metal

Qallačča is a key concept in Qaallu Institution. One instantiation of this complex concept is that it is a mysterious

sacred material culture (Fig.3). Informants tell us that true. qallačča worn on the forehead by the Qaallu was made of

iron that fell from sky as qorsa (comet, metorite); it was only recovered after pouring milk of a black cow on the specific

spot it dropped. For some ethnologists/anthropologists, it is a “white metal horn which is worn on the forehead” and is

“horn-symbolism” for “every man is a bull”, a symbol of virility (Bartels 1983: 146). For others it is just a ‘white

metal horn’ which is a symbol of fertility or just is “phallic ornament” (Haberland 1963:51 quoted in Bartels

1983:146). These argumentations share the root qaɾa ‘horn (sharp and tall), acute; graining fruit, granulate,

shoot’ and the inavariable qaɾ-ɳî ‘sex (characteristics)’. The very Oromo word for ‘sex (intercourse)’, namely

saala, also designates ‘horn, oryx, penis; awe, honor, esteem; shame, shameful’. But, these notions are only

part of the polysemantic and complex concept of qallačča. Amborn (2009: 401) might be wrong when he completely

rejects the “phallisphication” of qallačča by “some anthropologists”. He is right that qallačča is also a symbol

of “socio-religious mediator which is able to bundle positive and negative “cosmic” (for want of a better word)

energies” and rather “symbolizes a link between the human and the supernatural world; its function is to open

up this connection between different spheres.” Knutsson (1967:88-90 quoted in Bartels 1983:145) describes

qallačča as “a conically formed ‘lump’ of black iron…brought from the heaven by the lightening.” Plowman (1918:114), who took a sketch of qallačča (Fig.3 D), described it as “emblem” of the Qaallu “Chief Priest” or of the retired Abba Gadaa ‘the president’. Plowman fleshes out the components of qallačča: (1) “seven bosses superimposed on a raised rim running

round the emblem”; (2) “upright portion made of polished lead”; (3) “circular base of white polished shell-like substance resembling ivory”; (4) “leather straps for fastening emblem to forehead of weaver” (Plowman 1918:114). This mysterious cultural object has multifunction. Taaddasa Birbirsso Mootii, who is not only an informant, but, in the expression of the locals, ‘a man who has sipped mouthful’ (of Oromo traditional wisdom) explains the social epistemological structure underlying qallačča: During the time of Gada System, government by the people’s justice, the Waaqeeffataa used to pour out milk of black cow on Dibayyuu ritual and discover/see their qallačča [truth and abundance]. For it is a sacred object,

qallačča never moved [transported, communicated] withoutsacrificial blood of bulls. It must be smeared on

the forehead [See Fig.3A and P7B on the forehead]. How can urine/semen without water, child without blood, milk

without udder/teats be discovered [gotten]? In the aftermath of lengthy drought, too, they used to take

qallačča to depression/ford and hill-top to pray with one stomach [unanimously] to God with Qaallu the Spiritual

Father. Immediately, qallačča [God’s riposte] reconciled streaming milk from the sky [rains]. Hence, qallačča was

used for collective welfare. Qallačča is God’s qali ‘alethic truth, promise’. Note that from Laga Oda Cave, archaeologists (Brandt 1984:177) have found “‘sickle sheen’ gloss and polish”, which helped archaeologists to recover “possible

indications of intensive harvesting of wild grasses as early as 15, 000 B. P.”; “one awl”, “one endscraper” and

“one curved-backed flake” all “dated 1560 B.C.”; and, “a few microliths that show evidence of mastic adhering

close to the backed edges” which “strongly suggests” that by “1560 B.C…stone tools were being used (probably as components of knives and sickles).”

Qallačča and Gadaa—the generation-age-based

sociopolitical system

Baxter (1979:73, 80) calls it “phallic” or “ritual paraphernalia”, which is worn on the head “by men at crucial stage in the gaada [gadaa] cycle of rituals”. Informants make distinction between two types of qallačča: qallačča laafa (of the soft, acuminous), which is worn by the Qaallu or Abba Gadaa; and qallačča korma (of the virile man or bull, macho). Viterbo (1892) defines “kallaéccia”, qallačča as ‘disciple, pupil’, which cuts para-llel with the anthropologist Baxter (1979: 82-84) who

states that, in Oromo Gada System, a young man’s grown tuft (ɡuuɗuu; see Fig.3D; we shall come back to Fig.3A in the final part of the discussion) is “associated symbolically with an erect penis” and discourses that he is “guutu diira”, which means a “successful warrior”, the one who has reached a class of “member of political adulthood”, for he has “become responsible for the nation”. At this age, Baxter adds, “each of its members puts up a phallic Kalaacha”, a “symbol of firm but

responsible manliness.” The feminine counterpart to ɡuuɗuu hairstyle is “ɡuɖeya” (Werner 1914a: 141), guʈʈiya (literally go-away bird or its tonsure) or qarré ‘tonsure’ (literally, ‘kite’ or similar bird of prey) (Bartels 1983:262), while of the masculine qallačča head-gear is the feminine qárma (literally ‘sharpened, civilized’). In Gada System, this age-class is called Gaammee Gúɖ’ɡuɖá (reduplication ɡuɖá ‘big’) ‘Senior Gamme III’, the age of at which the boys elect their six leaders to

practice political leadership (Legesse 2006:124-125).

Bokkuu: Insignia of power, balance and light of

freedom

Hassen (1990:15) discusses that bokkuu has “two meanings”. One is “the wooden scepter kept by the Abba

Gada in his belt during all the assembly meetings”, an “emblem of authority…the independence of a tribe,

and…a symbol of unity, common law and common government” (Fig.4). De Salviac describes it “has the

shape of a voluminous aspergillum (a container with a handle that is used for sprinkling holy water) or of a mace

of gold of the speaker of the English parliament, but in iron and at the early beginning in hard wood” (De Salviac

2005 [1901]: 216). Legesse (2006: 104) describes it as “a specially curved baton”, which shows that there are two

types in use. The second meaning of bokkuu is, “it refers to the keeper of the bokkuu—Abba Bokkuu” (Hassen

1990:15), or in plural Warra Bokku “people of the scepter” (Legesse 2006: 104). Hence, after serving for full eight year, Abba Bokkuu must celebrate Bokkuu Walira Fuud’a (literally to exchange the scepter bokkuu), a Gada system concept

that refers to two socio-political “events as a single act of “exchange”” (Legesse 1973:81): (1) the event of power

“take over ceremony”, i.e., the symbolic act of “the incoming class” and (2) the event of power “handover

ceremony”, i.e., the symbolic act of “the outgoing class”. This power-exchange ceremony is also called Baalli

Walira Fud’a “Power Exchange” or “transfer of ostrich feathers” (Legesse 1973: 81-82; 2006: 125). Here, baalli

refers not only ‘power, authority, responsibility’ (Stegman 2011: 5, 68), but also ‘ostrich feather’ and ‘twig

(leaved)’, both of which are used as symbolic object on the Baalli power transfer ceremony. De Salviac (2005 [1901]: 216) witnessed “the power is transferred to the successor by remittance of the scepter or bokkuu.” After power exchange ceremony, the ‘neophyte’ Abba Bokkuu: “falls in his knees and raising in his hands the scepter towards the sky, he exclaims, with a majestic and soft voice: Yaa Waaq, Yaa Waaq [Behold! O, God!] Be on my side…make me rule over the

Doorii…over the Qaallu…make me form the morals of the youth!!!…” (De Salviac 2005 [1901]: 213). See Fig.4B.

Then, the new Abba Bokkuu takes possession of the seat and “immolates a sacrifice and recites prayers to obtain

the assistance of On-High in the government of his people….The entire tribe assembled there, out of breath

from emotion and from faith” (De Salviac 2005 [1901]: 212). Above we raised that two symmetrical acts/concepts are

enfolded “as a single act [or word] of “exchange”” is performed by exchanging the Bokkuu scepter during

Baalli ceremony (Legesse 1973:81). That is, when the scepter is the one with bokkuu ‘knobs’ on each edge, it

suffices to enfold it ‘Bokkuu Baalli’ since the symmetricality principle of the act of reciprocal remittance

or power exchange is as adequately abstracted in the phrase as in the iconicity of the balanced bokkuu. Besides, the horooroo stick with a knob (bokkuu) on one side and a v-/y-shape (baalli) on the other side is a semagram and semotactic for the same concept of symmetricality principle, i.e., Bokkuu Baalli.

Ateetee in Qaallu Institution: Fertility symbolism

Cerulli (1922:15, 126-127) “Atētê …the goddess of fecundity, worshipped by the Oromo” and adds that “the

greatest holiday of the [Oromo] pagans is the feast of Atetê”; she is “venerated” by “even the Mussulmen”; she

is referred to “in the songs ayô, ‘the mother,’ often with the diminutive ayoliê, ‘the little mother’”. Women sing

“songs asking the goddess to grant them fecundity and lamenting the woes which are caused by sterility.” Long

before Cerulli, Harris (1844:50) wrote as follow: “when sacrificing to Ateti, the goddess of fecundity, exclaiming

frequently, “Lady, we commit ourselves unto thee; stay thou with us always”.”

The symbolic material cultures pertaining to Aɖeetee are important for our purpose in this paper. Bompiani

(1891:78) saw the Oromo on their “long journeys to visit Abba Múdā” who, “as a sign of peace they make a sheep

go before them on entering the village… and instead of a lance carry a stick, upon the top of which is fixed the horn

of an antelope” (this is well known Ancient Egyptian hieroglyph). Indeed, sheep (ḫooɭaa), common in ancient

rock paintings of Hararqee, is also the favorite for sacrificial animal for Qaallu institution of “peacemaking

and reconciliation”, particularly black sheep, “a sheep of peace” (hoolaa araaraa)” (Gidada 2001: 103). In fact, the

word ḫooɭaa for ‘sheep’ and rêeé, re’ee for ‘goat’ (re’oṱa, rooɖa, plural) have meronymic relationship. The semantic

structure underlying both is ‘high fertility rate’ (arareessá, from ɾaɾí ‘ball, matrix; pool, rivulet’). The “antelope” that Bompaini names is in fact the beautifully speckled ʂiiqqee ‘klipspringer’ (Stegman 2011:45, 35), common in Laga Oda and other paintings along with ‘fat-tailed’ sheep. At the same time, ʂiiqqee (literally, ‘splendid, lustrous, graceful’) is, according to the

Aṱeetee Institution, a sacred, usually tall and speckled, “stick signifying the honor of Oromo women…a blessing… a ceremonial marriage stick given to a girl…a religious stick Oromo women used for prayer” (Kumsaa 1997:118). Kumsa observed that “the very old, the very young and all women, in the Gadaa system, are considered innocent and peace-loving” and quoted the renowned anthropologist Gemetchu Megerssa who expressed that in Oromo Gada tradition women “were also regarded as muka laaftuu (soft wood–a depiction of their liminality) and the law for those categorized as such

protected them” (Kumsa 1997:119). Concentric or circular or ‘sun-burst’ geometric motifs are as abundant as ‘udder chaos’ in the Hararqee and Horn of African ancient rock paintings (Fig.5C from Qunnii or Goda Ummataa; A and B Goda Roorris traditionally known as ‘Errer Kimiet’; G from Goda K’arree Ğaldeesaa or Weybar in Č’elenqoo; E Laga Oda from Cervicek

1971). Bartels (1983) studied well about another symbolic object in Aɖeetee Institution, namely ɡuɳɖo, a grass-plate, made from highly propagative grasses, plaited in a series of concentric-circles (see Fig.5D). It is used to keep bîddeena ‘pizza-like circular bread’ and fruits. Bartels (1983: 261) documented that, on her wedding day: [T]he girl has with her a grass-plate (gundo), which she made herself. This gundo is a symbol of her womb [ɡaɖāmeʑa]. Since…she is expected to be a virgin

[ɡuɳɖúɖa], nothing should have been put in in this grass plate beforehand. Gundo are plaited [with an awl] from

outside inwards, leaving a little hole in the centre [ɡuɖé, qaa]…this little hole is not filled in by the girls themselves,

but they ask a mother of a child to do it for them. If they do it themselves, they fear they will close their womb to

child-bearing (Square brackets added).While, ɡuɳɖó stands for a woman’s gadameʑa ‘womb’ (from gadá ‘temple; generation, time-in-flow), the concentricity of the plaits (marsaa, massaraa, metathesis) is a symbol of the ‘recyclers’ of generations, namely mûssirró ‘the bride-woman’ and marii ‘bride-man’ (marii also means ‘cycle, inwrap, plait’). A bigger

cylindrical ɡuɳɖó with cover called suuba is particularly given as hooda ‘a regard’ to the couples (on their good

ethos, virginity) and is a symbol of súboo ‘the newly married gentlemen, the prudential gentlemen’. Father Lambert Bartels (Bartels 1983: 268) wrote that a buffalo-killer would bring a special gift for his mother or wife from the wilderness: namely, elellee (elellaan, plural) from his buffalo skin” Elellee and č’aačč’u refer to a string of cowries (of snail shells, obsidian rocks or fruits of certain plant called illilii) and festooned to a sinew cut from a sacrificial animal (Fig.5F). They are worn only by

women on the breastplate or forehead or worn to č’ooč’oo, č’iič’oo milk-pots, symbol of “a woman’s sexual and reproductive organ” (Østebø 2009: 1053). See also Fig.5F and G.

We need to add here a praise song to a beauty of woman, which symbolizes her by élé ‘circular cooking pot or oven made of clay’ and bede smaller than élé (Sumner 1996: 68): Admiration is for you, o <ele>… <But> I take out of <bede>…

Admiration is for you, moon shaped beauty. Rightly, Sumner (1996:68) states élé symbolizes “the mother, of woman” while bedé symbolizes “daughters” or the “moon [báṱí] shaped beauty”, i.e., her virginity (ɡuɳɖuɖa), uncorruptedness (baʤí) combined with ethos of chastity (aɖeetee). Woman is expressed arkiftu idda mačč’araa literally ‘puller of the root of one-body/-person’,a paraonomastic way to say circulator, recycler or propagator of the genealogy of Oromo moieties, namely

Mačč’a and Raya/Raã. Here, it is fascinating to observe the unique social semiosis at work—selecting and stitching (qora) the language and world according to the semblance and image the reality (world) offers as a cognitive possibility to operate upon. cowries of “giant snail shells…kept with a string made.

Spear piercing coffee bean

According to the Aṱeetee tradition, on her wedding ritual, the bride “hands her gundo to her mother-in-law who puts

some sprouting barley-grains in it. They are (a symbol of) the children Waqa will give her if he will’’ (Bartels 1983:

261). The mother-in-law will, according to the long tradition, adds some coffee-beans (coffee-beans and

cowries are look-alike, Fig.5 F from Cervicek 1971 and H); “coffee-beans are a symbol of the vagina,

representing the girl to be a potential mother. The beans are children in the shell at this moment, protected and

inaccessible as a virgin’s vagina” (Bartels 1983:261). Later on during the ritual, the elderly bless her: “May

Waqa cause the womb [gundo] sprouts children [grains]! Let it sprout girls and boys!” Amid the ceremony, the

bride “gives the gundo to her groom’s mother. She herself now takes his [bridegroom’s] spear and his stool.

She carries the stool with her left hand, holding it against her breast. In her right hand she grasps the spear….”

The spear, a representation of the male organ, is expressed in the Girl’s Song:

O sheath [qollaa] of a spear,

Handsome daughter,

Sister of the qaɽɽee [us colleagues of marriage-age]

Let us weep for your sake

The buna qalaa ‘slaughtering of coffee fruit’, which reflexes, in direct translation, the ‘slaughtering’ (qaɭa) the

virgin is “a symbol of procreation” (Bartels 1975: 901). The bride “puts the coffee-fruits from the gundo in butter

together with others and put them over the fire” (Bartels 1983: 263). Butter (ɗ’aɗ’á) is a symbol of fecundity

(ṯaɗ’āma) while the floor of the fire, or hearth (baɗ’ā) is a symbol of the nuclear family that is taking shape

(Legesse 1973:39). While, all this was captured by Bartels in the late 20th century in Wallagga, Werner (1914

b: 282) captured similar events a thousand or so kilometers away at Northern Kenya with the Booran:

On the wedding morning, a woman (some friend of the bride’s mother) hangs a chicho [č’iič’oo, č’ooč’oo] full of

milk over the girl’s shoulder….The bridegroom, carrying his spear and wearing a new cloth and a red turban, goes

in at the western gate of the cattle-kraal and out at the eastern, and then walks in a slow and stately way to the

hut of his mother-in-law, where the bride is waiting for him. They sit down side by side just within the door; after

a time they proceed to the cattle-kraal, where his friends are seated. She hands him the chicho and he drinks

some milk, and then passes it on to his friends, who all drink in turn.

In general, matrix-shape, milk-pots, sprouting beans all symbolizes feminineness quality, the natural power to

‘reproductive faculty’ (ʂaɲɲí), a capacity to generate many that, yet, keep alikeness or identity (ʂaɲɲí).

Woman and a cow and infant and a calf

Cows are “a symbolic representation of women” (Sumner 1997: 193; Bartels 1975: 912) because both are equally

haaɗ’a manaa ‘the flex of the home/house’:

Sawayi, ya sawayi—o my cow, o my cow [too high

hypocorism]

ʼnīṱī abbaan gorsatu–a wise man’s wife/a wife of wisest

counselor husband

amali inmulattu–her virtues are hidden;/is virtuous and

has integrity;

saa abbaan tiqsatu–o careful owner’s cow/ similarly, cow

that the owner himself

shepherds/feeds

č’inaači inmuľaṱu–her ribs are hidden/her hook bone is

invisible (full and swollen).

Saa, saa, ya saa–cattle, cattle, o cow,

ya saa marī koo–o cow, my advisor/darling

ţiqē marartu koo–good in the eyes of your herdsman/am

overseeing you spitefully.

(Bartels, 1975: 912)

Likewise, an infant and a young calf are not only congruous, but also sung a lullaby to comfort them:

Sleep, sleep!

My little man slobbers over his breast.

The skin clothes are short.

The groin is dirty

The waist is like the waist of a young wasp

The shepherd with the stick!

Sleep, sleep!

He who milks with the ropes!

Sleep, sleep!

He who takes the milk with the pot!

Sleep, sleep!

The cows of Abba Bone,

The cows of Dad’i Golge:

They’ve gone out and made the grass crack;

They’ve [come home] again and made the pot.

(Sumner 1997: 181)

Basically, there is no difference between a newborn calf and an infant; no need of separate lexisboth is élmee—

diminutive-denominative from elma ‘to milk’. Young calves or children are worn kolliʥa ‘collar’, ǧallattii

‘diadem, crown, tiara’ or č’allee ‘jewelry’ wrapping around their necks, all of whose semiotic significance is to

express ǧalla, ǧallačča ‘love’ and protection from ɡaaɖiɗú ‘evil spirit’ that bewitches not only infants and young of

animals, etc (Bartels 1983: 284-285, 196-197). The first meaning of ɡaaɖiɗú, gádíṱú is ‘silhouette’ or ‘human

shadow’ (see also Tutschek 1844: 54), but, in this context it refers to an evil spirit that accompanies or inhabits a

person. The evil spirit comes in a form of shadow and watches with evil-eye, hence it is also called, in some areas, ɮaltu, ilaltu ‘watcher (wicked)’. All these concepts are common motifs in Hararqee rock paintings (Cervicek 197). See

Fig.6 especially the silhouette-like background and in C an evil-eye motif is seen watching from above.

In accordance with the Qaallu Institution, the Qaallu (or Qaalličča, particulative) receives and embraces new

born children, giving them blessings, buttering their heads and ɡubbisaa ‘giving them names’, literally,

‘incubating’ from ɡubba ‘to be above, over’ or ɡuƀa ‘to brand, heat’ (Knustsson 1967). Women call this process of entrusting children to the Qallu ‘aɖɖaraa ol kaa’, literally ‘Putting/Lifting up oath/children to the topmost (related to the prayer epithet Áɖɖaraa ‘Pray! I beseech you!’). Or, they call it Ők’ubaa ɢalča, literally ‘entering/submitting the Őq’ubaa’, which refers to “the act of kneeling down and raising one’s hands with open fingers towards the sky (Waaqa) and thus submitting oneself to Waaqa” (Gidada 2006:163), from the prayer epithet: Őq’uba ‘Pray!, Prayer!’, literally,

‘Take my fingers!’ A “perfect attitude at prayers in the Oromo’s eyes is to lift the hands towards heaven”

(Bartels 1983: 350). An unfortunate Oromo father/mother has to but say élmee koo ana ǧalaa du’e, literally ‘my offspring/child died from under/underside me’ while an unfortunate child would say abbo/ayyo koo ana’irraa du’e ‘my dear dad/mum died from above/over me’. Some lines from a song for a hero illustrate caressing and kissing the belly of his mother (Cerulli 1922: 48):

The belly which has brought you forth,

How much gold has it brought forth?

Who is the mother who has given birth to you?

If I had seen her with my eyes,

I would have kissed her navel.

These symbolic-actional rhetorical organizations are most probably the underlying ‘grammar’ of the recurrent

anthropomorphic signs, along with a newborn calves, ‘embracing’ the belly, navel of a cow (Fig.6CandD from

Cervicek 1971). Culturally, cows are given as an invaluable gift to an adoptee child, so that she/he never

sleeps a night without a cup of milk. The gift-cow is addressed by hypocoristic aɳɖ’úree ‘navel, umbilical cord’

(aɖɖ’oolee, plural, by play on word ‘good parous ones, the gray/old ones’), which means ‘dear foster-mama’

symbolizing cordiality, wish to long-life and strong bond, protection of the child (see also Hassen 1990: 21).

Earlier in this paper, we saw how matrilineal-patrilineal and moiety phratry are represented partly by bovine

anatomy. As recorded by the Catholic Father Lambert Bartels and others, Waaqa ‘Devine, God, Sky’

symbolizes Abbá, Patriarchic-side of the cosmos or Father or Husband “who goes away” while, Daččee

‘Earth’ symbolizes, the Matriarchic-side, Mother or Wife who “is always with us” (Bartels 1983: 108-111) and

“originally, Heaven and Earth were standing one next to the other on equal terms” (Haberland 1963: 563 quoted in

Bartels 1983: 111). As we observe the Laga Odaa pictures (see Fig.5A), we consistently also find another

interesting analogy–bulls are consistently drawn above the cows. In Oromo worldview, a bull represent ßoo

‘sacred domain of the male’ (vocative form of bâ ‘man, subject, being, masculine 4th person pronoun’), while a

cow (saa, sa’a) represent çâé, îssi ‘sacred domain of the female’ (also ‘feminine 4th person pronoun’) (Kassam

1999:494). From this worldview comes Oromo concept of Ḿootumma ‘rule, government, state, kingdom’:[Ḿootumma comes] from moo’a, autobenefactive: moo’ď/ʈ, is a cattle image. For example, Kormi sun him moo’a, “that bull is in heat” and sa’a sun iti moo’a ‘he is mounting that cow’. With reference to human beings, the implication is not necessarily sexual, but can denote superiority or dominance in general. An moo’a, an mooti is a formula of self praise by a new Abba Gada during his inauguration (Shongolo 1996: 273).

Qallačča and Qaallu: A jigsaw motif

In this last section of this analysis, we must consider the symbolic significance of what an old man skilled in

Oromo oral history says is tremendously important: The Qaallu did this. For the daughter/girl of Ǧillee

[eponymous clan name] he took a heifer; for the daughter/girl of Elellee [eponymous clan name] he also

took a heifer. Then, for the Elellee girl he erected the heifer of Elellee in such a way that her (the heifer’s) head

is faced upwards. For the Ǧillee girl, he erected the heifer of Ǧillee in such a way that her (the heifer’s) is faced

downwards. The girl of Ǧillee too siiqqee stick and hit the Mormor River; then, the Mormor River split into two

(BATO 1998:75; My translation).

This story offers us a tremendously important insight.It corresponds with the amazing critical observation and re-interpretation of my informant Muummee. Muummee rotated 90oCW Cervicek’s (1971) Laga Oda Figure 47 (=

Fig.7 A) and got Fig.7B after rotating. In this motif, the Qaallu , with his qallačča headgear, is at the centre. We

can observe one heifer above the Qaallu (perhaps Ǧillee heifer) her head inverted, serving as qallačča headgear,

and behind him to the right handside, two heifers (cattle, one headless), both of whose heads are facing

downwards but in between them and the qallačča cattle is one anthropomorphic motif, unlike on the lefthand

where there are many, possibly a chorus in praise of the sublime black cow and of the reverenced Qaallu. We also

observe, a heifer (cow?) whose head is faced upwards (possibly Elellee heifer).

As usual, it is likely also that this style is as much for associal-epistemological as is it for grammatical- semotactical reason. The downward-faced heifer or Ǧillee (hypocoristic-diminutive from ǧiɭa ‘ritual ceremony, pilgrimage’), which is equivalent to qallačča headgear of the Qaallu anthropomorphic, is a signification of the semantic of ɡaɮa ‘to safely travel away and come home (or ɢaɮma ‘the Sacred Temple of Qaallu’)’ by the help of the Qallačča the providence of God. Thus, the collocation

forming gaɮa-gaɮča gives the polysemous metonymic senses: (1) to invert, make upside down, (2) one who causes safe home-come i.e., Qallačča. The same ‘play on word’ is true of Elellee: (1) reduplication (emphasis) of ēɮ, éla ‘spring up; well (water)’, and (2) őɮ literally ‘go up; upwards; spare the day peacefully, prevail’. “Őɮa!” is a farewell formula for ‘Good day!’ (literally ‘Be upward! Be above! Prevail!’).Yet, the most interesting aspect lies beyond the lexico-syntactic or semotactic motives. If we look carefully at this motif, the head of the Qaallu and the foreparts of the downwards (ɡaɗi) Ǧillee heifer merge, which makes the latter headless (ɡaɗooma). The Elellee heifer apparently with only one horn but full nape (bok’uu)

appears to be another jigsaw making a thorax (ɡûɗeɫča) of the Qaallu, possibly because in the “Barietuma” Gada

System, the Qaallu are “central”, i.e., “occupy a special position, and their members act as “witnesses” (Galech)

on the occasion of weddings or other important transaction” (Werner 1915:17, 1914a: 140; See also Legesse 2006: 104, 182, for “Gada Triumvirate System”). This is not arbitrary, but is stylized so that the notions of seniority are textured simultaneously, in caput mortuum. Pertaining to the “seven bosses” of the qallačča (Plowman 1918:114) ) is possibly equivalent to Cervicek’s (1971:192) description of this same motif: “Seven animal representations, painting of a symbol ((cen-tre) and pictures of H-shaped anthropomorphic figures…Painted in graphite grey, the big cattle picture a

little darker, the smaller one beneath it in caput mortuum red.” While we can consider, following Dr. Gemetchu Megerssa, anthropology professor, that the seven bosses might stand for the seven holes of human body (above the neck) which still stand for some mythical concepts we cannot discuss here, it is also possible to consider the (related) socio-political structure of the democratic Gada System. They must stand for what Legesse (1973: 82, 107) calls “torban baalli” “the seven

assistants” of Abba Gada in “power” (his in-powerness is makes him Abba Bokkuu, ‘Proprietor/Holder of the

Scepter’). Long before Legesse’s critical and erudite study of Gada System, Phillipson (1916) wrote:

The petty chiefs act in conjunction with the king. These are, however, appointed by election of officers called Toib

[Tor b] or Toibi (= seven councilors or ministers). These are men of standing and character…. They are governed

by, and work in unison with, the head. These officers are appointed by the king, and each of the seven has an

alternative, so that the number is unbroken. Their office is to sit in council with the king, hear cases, administer

justice, and in the king’s absence they can pass sentence in minor cases; but all they do is done by his authority.

For all that, this may act as a check if the king inclines to despotism. There is no such thing as favoritism; the Toibi

stands in the order elected: 1, 2, and c (Phillipson 1916:180). These seven high ranking officials (aɡaoɗa) are

purposely represented by forepart of bovine body (agooda), because this is the strongest and most

powerful part. Ól, literally ‘up, upwards, upper’ is a metaphoric expression for those “On-High in the

government of his [Abba Bokkuu] people” (De Salviac 2005 [1901]: 212). Cervicek (1971:130) is accurate when he theorized “anthropomorphic representations do not seem to have been painted for their own sake but in connection with the cattle and symbolic representations only.” Despite the guttural sounds dissimilarization, as in the expression

ɢaɮčaan naaf ɡalé ‘I understood it by profiling. i.e., symbolically (i.e., from the gerundive ɢaɮču, kalču ‘profiling, aligning, allying’, or kaɬaṯṯi ‘perspective, façade’, or the base kala, χala ‘to construct, design’; see Stegman

2011:2, 17), the very word qallača itself is a metasemiotic language, meaning ‘symbolic interpretation’.

*Dereje Tadesse Birbirso (PhD) is Assistant Professor, School of Foreign Language, College of Social Science and Humanities, Haramaya University

Read full article @ http://internationalscholarsjournals.org/download.php?id=275978303829134960.pdf&type=application/pdf&op=1

You must be logged in to post a comment.